62 Maps

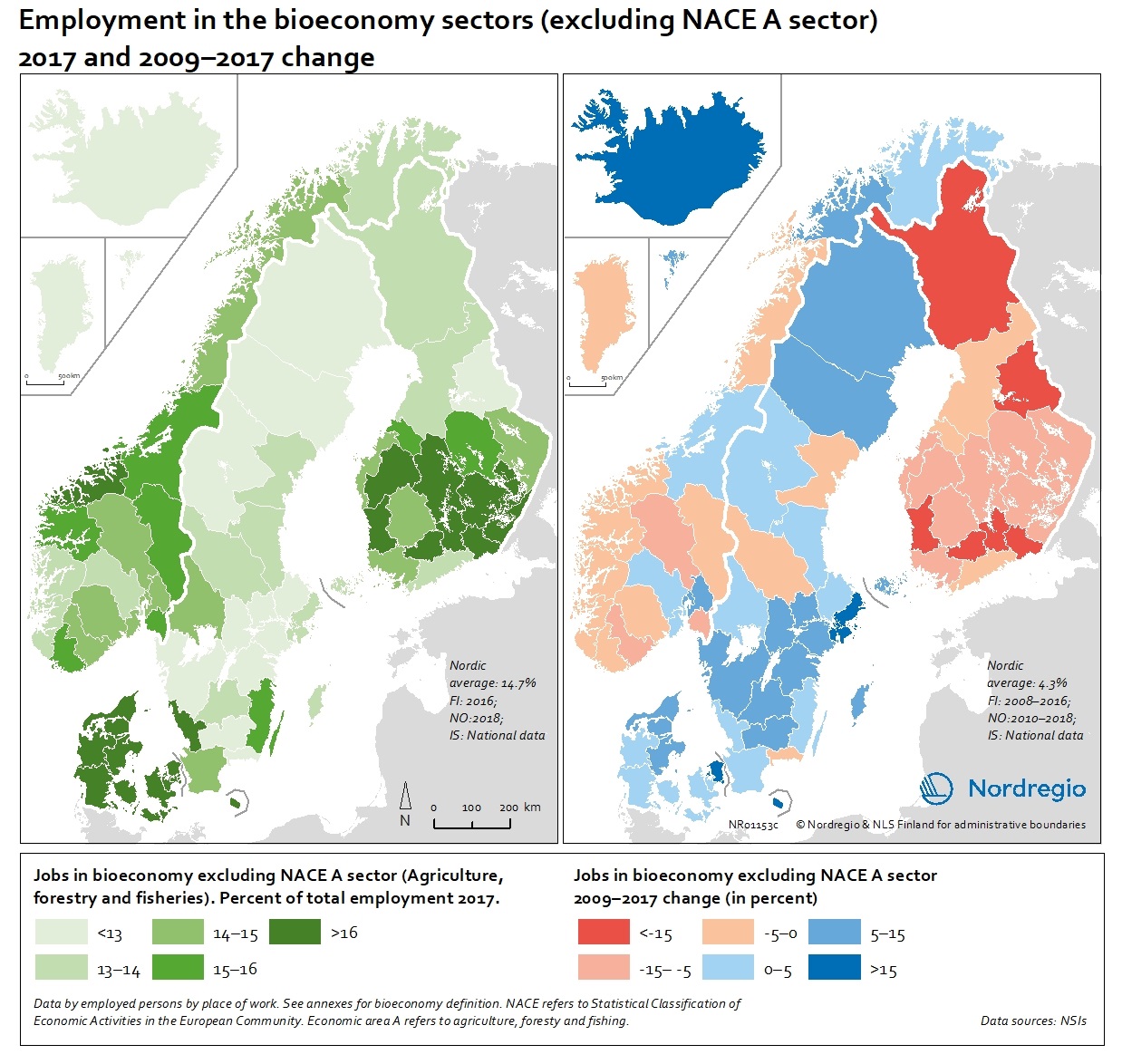

People employed in the bioeconomy excluding NACE sector A in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These maps show the number of jobs in the bioeconomy sectors as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right), excluding the NACE A sectors. The non-NACE-A sectors have seen a more moderate decrease in Finland but a noticeable increase in most parts of Sweden, Denmark and the Faroe Islands and a remarkable increase in Iceland with more than 15% (Figure 9.3). The average increase in the Nordic Region is 4.3% in the non-NACE-A sectors. There are also notable differences within the countries, showing that regional differences matter. In Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, there is a positive trend in most regions, but in Finland, almost all regions are losing jobs in the primary industries. In Norway and Sweden, some regions show positive development while others are in decline. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

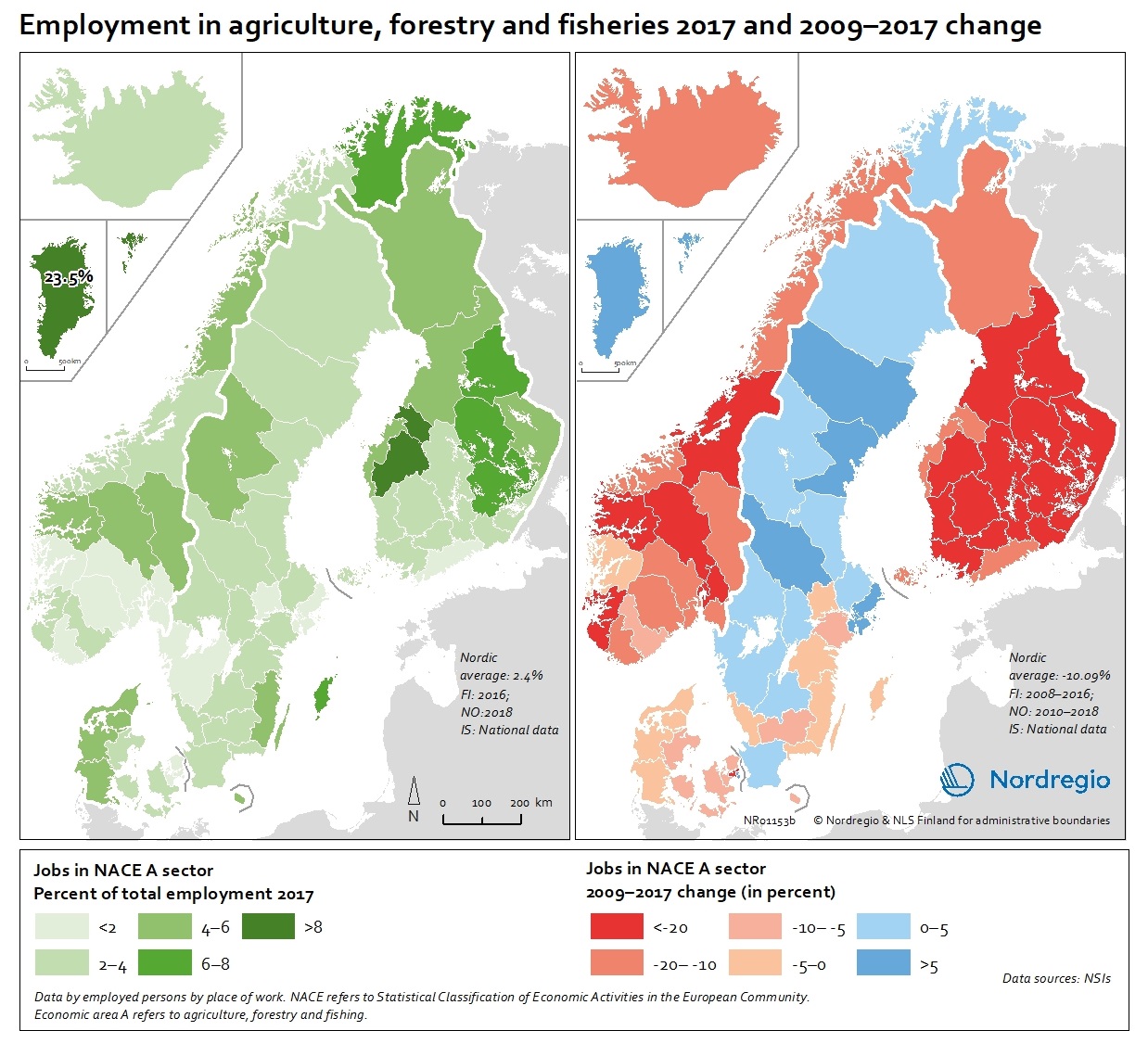

People employed in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors (NACE Sector A) in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These map show the number of jobs in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors (NACE A sectors) as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right). The map (left) indicates ranges of people employed in agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors between below 2% to above 8%, with the highest proportion being in Greenland with 23.5% in 2017. In the EU-28, the overall proportion of the total workforce with jobs in the NACE-A sectors is an average of 4.6%. Overall, the NACE-A sectors show a sharp decline in employment (right map), particularly in Finland, Iceland and Norway (except northern Norway), where the decline was up to 20% between 2009 and 2017. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

People employed in the bioeconomy including NACE sector A in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These maps show the number of jobs in the bioeconomy sectors as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right). The share of jobs in the bioeconomy varies from below 15% to above 22.5%. For instance, in the western regions of Denmark, the central and southern regions in Finland, Greenland and some mid and northern regions of Norway, over 22.5% of the working population is employed in the bioeconomy. At the same time, most regions in mid-Norway, in all Finnish and some Danish regions witnessed negative development in jobs in the bioeconomy. In Greenland, Iceland, Faroe Islands, Sweden, Northern Norway and other parts of Denmark the situation is very different and the number of jobs in the bioeconomy has increased. These proportions should also be seen in relation to the increase in total number of jobs17 in most regions in the Nordic countries except for the Finnish regions and Åland where there is a decline in most regions. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Population change in Arctic settlements

The map provides an overview of the population change in Arctic settlements with 500 inhabitants or more during the period 2000 to 2017. The purple underlaying layer shows the extent of permafrost across the Arctic. The circles indicate settlements with 500 inhabitants or more and are proportional to the total population in 2017. Blue tones indicate population growth between 2000 and 2017, while red tones indicate population decline. Four zoomed-in maps show areas with high settlement density – Arctic Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Alaska. In Alaska, population increased in the largest settlements between 2000 and 2017. The population decline in small settlements located far from the two large cities – Anchorage and Fairbanks – has been caused by outmigration, which has cancelled out the positive natural population growth. In the Canadian Arctic, most people live in a few settlements. Similar to Alaska, the population increased in the largest settlements and decreased in small settlements. Most of the smaller settlements in Arctic Fennoscandia have witnessed a population decline between 2000 and 2017, except in Norway. The dominant pattern in Fennoscandia is a population growth in larger settlements and a population decline in surrounding smaller settlements. This is similar to the pattern observed in the other Nordic Arctic countries – Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands. New inhabitants settled in the capitals (Reykjavik, Nuuk, and Torshavn) and regional centres, from both domestic and international locations, while settlements in sparsely populated areas are becoming less attractive to incomers. In the Russian Arctic, the regions can be divided into the oil and gas areas of the Khanty-Mansi and Yamal-Nenets, and other areas. The population is growing in the oil and gas areas and declining slowly in the others. Over 75% of the settlements have been shrinking throughout the 21st century, mainly because…

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

- Migration

Indigenous population in the Arctic

The map shows the indigenous population as a share of the total population in the Arctic. Approximately one million people, or 9% of the total population in the Arctic is indigenous. Indigenous population reassembles more than 40 different ethnic groups. In terms of statistics there are no circumpolar definition of an indigenous person and therefore the number of indigenous people is based on different national definitions. Official statistics do not necessarily recognize indigenous populations separately. The indigenous population is the highest in the Canadian Arctic and in Greenland, weighing more than 75% of the total population. The Yukon, the southern part of Northern Quebec, and Labrador and Newfoundland (Canada) have the lowest shares of indigenous population. In the remaining part of the Arctic, indigenous peoples represent less than half of the total population, except in Sakha (Russian Federation), Southwest Region and Northern Region (Alaska, USA) where 50-75% of the population is indigenous. There are no indigenous people in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Svalbard.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

Origin of FDI inflows 2003-2016

This map shows the country of origin of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the Nordic regions between 2003 and 2016. The colours indicate different countries of origin of FDI inflow by number of projects between 2003 and 2016. FDI inflows examined by country of origin, reveal an interesting pattern in terms of intra-Nordic investment inflows, confirming the assumption that proximity, both in terms of geographical distance, and in terms of rules, regulation and business culture is an important driver of FDI. A breakdown at the regional level reveals that 55 out of the 74 Nordic regions received the largest number of FDI projects from a region located in another Nordic country. The largest share of these intra-Nordic flows originates from Sweden (35 regions in total), particularly in the manufacturing sector as well as the ICT sector in Norway. The largest share of FDI projects from Finland are attracted to Sweden’s highly competitive international manufacturing industry. Denmark is the main source country of FDI inflows in both Greenland (mostly in the transportation and storage and business services sectors) and the Faroe Islands (mostly manufacturing and finance and insurance activities sectors). Eighteen Nordic regions have their largest source country in terms of project located outside the Nordic Region, i.e. other European and extra-European countries. FDI inflows from other European countries are the highest in terms of projects in six Nordic regions, most of these regions can be characterised by their relative remoteness and strong industrial profile. Finally, two extra-European countries, namely the United States and Canada, are the largest source country in twelve Nordic regions, that are either capital city regions with a strong and diversified service sector or peripheral industrial regions.

2018 December

- Economy

- Nordic Region

Relative local employment effect 2008-2016

The map shows the change in jobs (growth or decline) at municipal level over a period that can be attributed to local factors (e.g. local policies or local natural or institutional conditions) and is thus not due to national or industry trends. The map is based on shift-share analyses which can help answer why employment is growing or declining in a local or regional industry. This type of analysis can answer questions like: How much of local job growth can be attributed to expected national and sectoral trends and how much is due to local factors Is the local economy growing or declining? How does the community compare with other communities? What are the local strengths and weaknesses in providing jobs and in which sectors? What industries are doing well? What industries should be targeted? There are large differences between municipalities in terms of the change in employment due to local factors. For example some of the municipalities in Mid Jutland in Denmark show a high local employment effect while others in the North of Jutland do not. These differences can be due to access to markets, to industrial culture, to municipal or regional facilitation etc. In-depth research is needed in order to understand the reasons. The map does not show the total change in jobs.

2018 June

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Employment rate 2016 related to the EU2020 goal and 2009-2016 change

This map shows the employment recovery from the financial crisis, with the employment rate (20-64 years) in European regions in 2016 related to the EU2020 goal of 75%, as well as the change in the employment rate between 2009 and 2016. The green colour indicates regions with employment rates above 75% and an increase in the employment rate between 2009 and 2016. The red colour indicates regions with employment rates below 75% and a decrease in the employment rate between 2009 and 2016. The yellow colour indicates regions with employment rates above 75% and a decrease in the employment rate between 2009 and 2016. The blue colour indicates regions with employment rates below 75% and a decrease in the employment rate between 2009 and 2016. The grey colour indicates regions with no data available. On a European scale, the effect of the financial crisis on employment became noticeable from 2009 onwards when average employment rates started to decline. This continued until 2013 when the average European employment rate reached its lowest level of 68.3% for the age group 20–64 years. After 2013 the employment rate started to rise again but it took until 2016 for the average European employment rate to reach and then surpass pre-crisis levels. In 2016 the average employment rate in the European union was 71%, edging closer to the EU2020 goal of 75%. In some regions, primarily in southern Europe, employment rates have still to recover to pre-crisis levels. This is particularly so for Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal which were particularly hard hit by the debt crisis and thus had to undertake massive cuts across the public sector. On the other hand, some countries such as Germany, Austria and Switzerland saw rising employment rates even during the financial crisis. The differential nature of outcomes in…

2018 February

- Europe

- Labour force