66 Maps

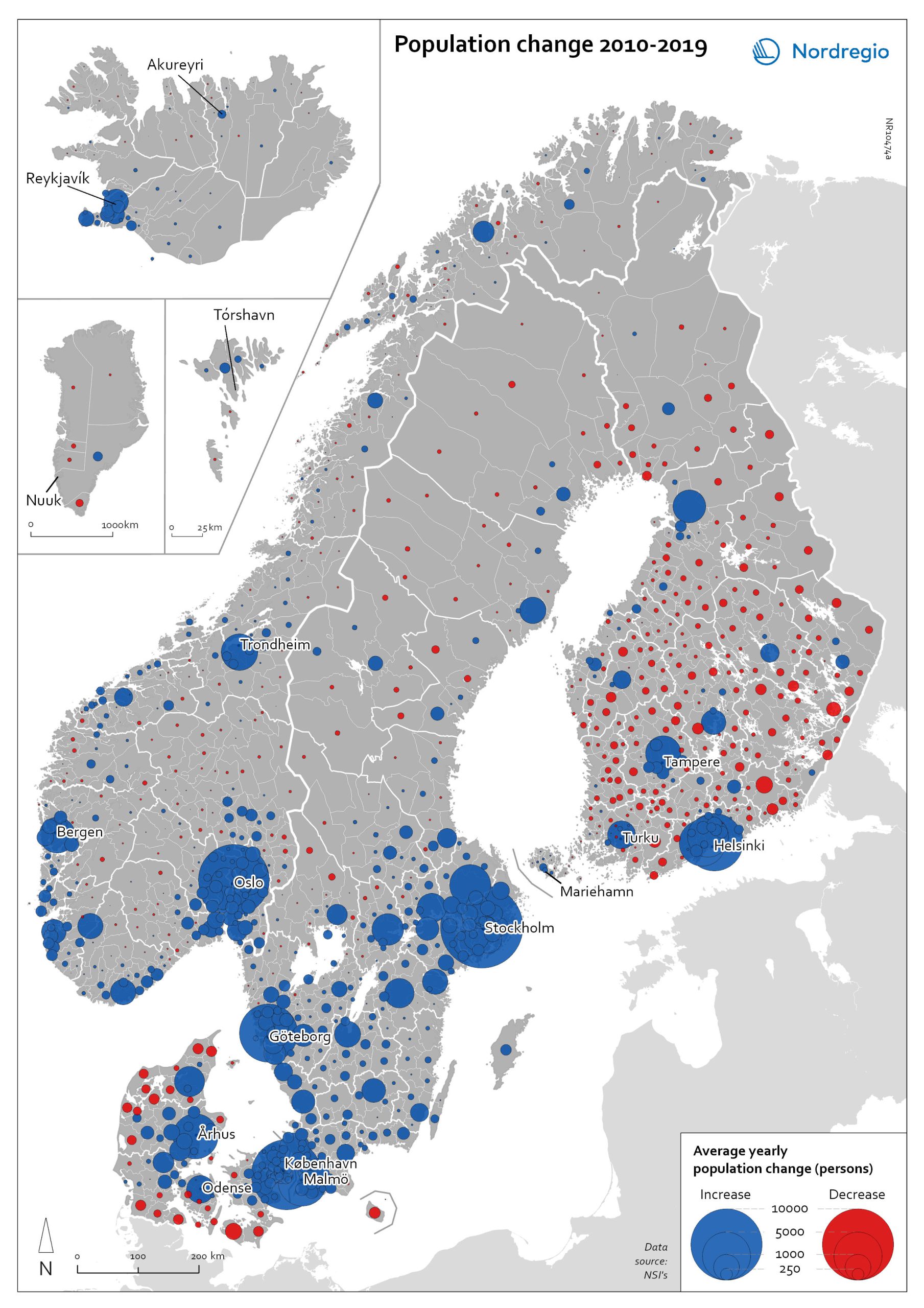

Population change 2010-2019

The map shows the type (positive or negative) and size of population change from 2010 to 2019 in all nordic municipalities. In Finland, Denmark, and Greenland there is a clear pattern of population growth in and around the larger cities and population decline in rural areas. Geographical and administrative differences mean that a much larger number of rural municipalities in Finland are dealing with population decline. Sweden experienced substantial population growth between 2010 and 2019, primarily due to high levels of international immigration. As a result, many rural areas also experienced population growth, particularly in the south of Sweden. However, in the more sparsely populated municipalities in the north of Sweden, the pattern is somewhat similar to that observed in Denmark and Finland, albeit with population decline in lower absolute numbers. Both Iceland and the Faroe Islands experienced substantial growth of their tourism industries within the period. This enabled some rural areas to maintain or even grow their populations. Norway exhibits more balanced population development in general, with a mix of population growth and decline in rural areas throughout the country.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

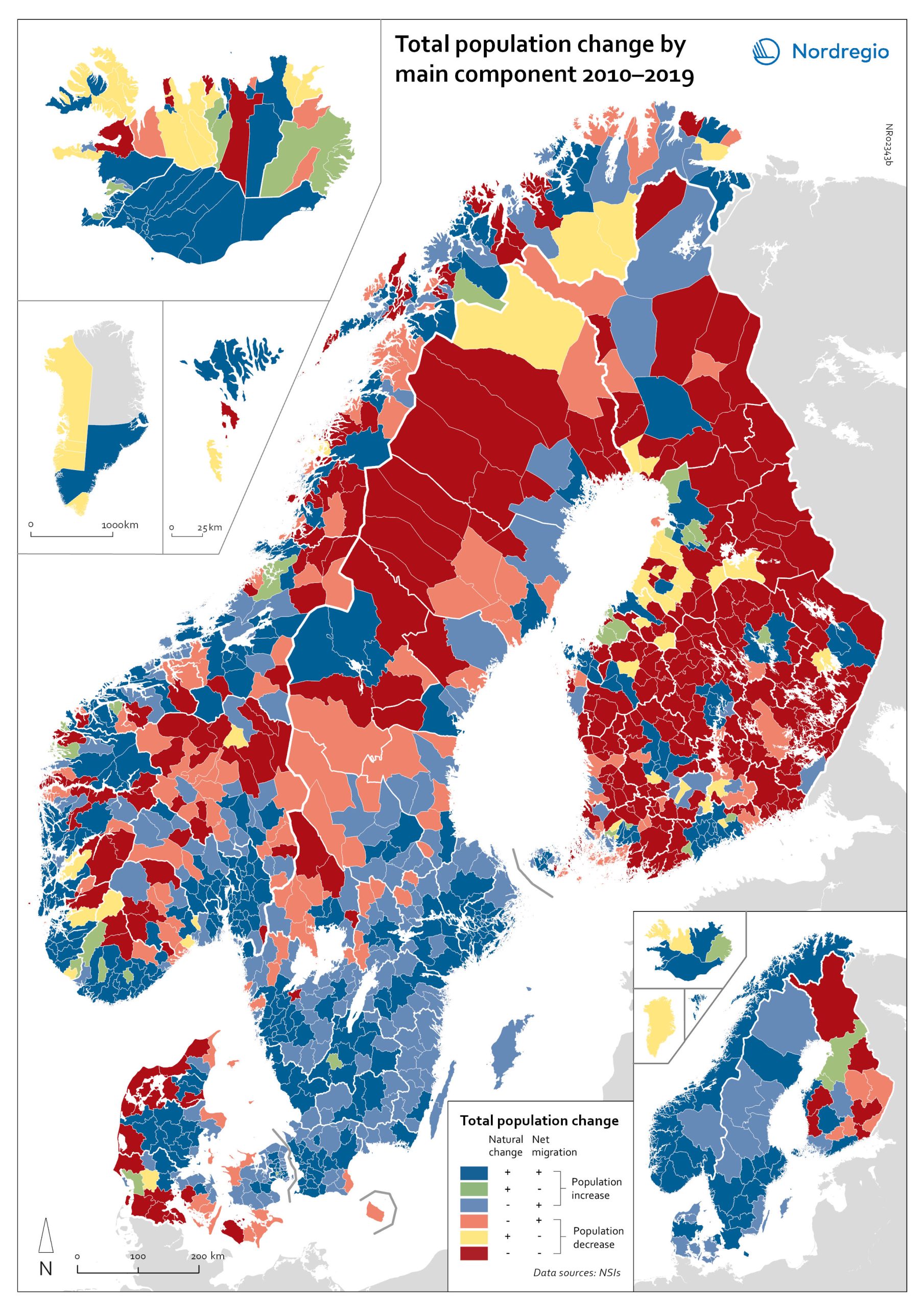

Population change by component 2010-2019

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

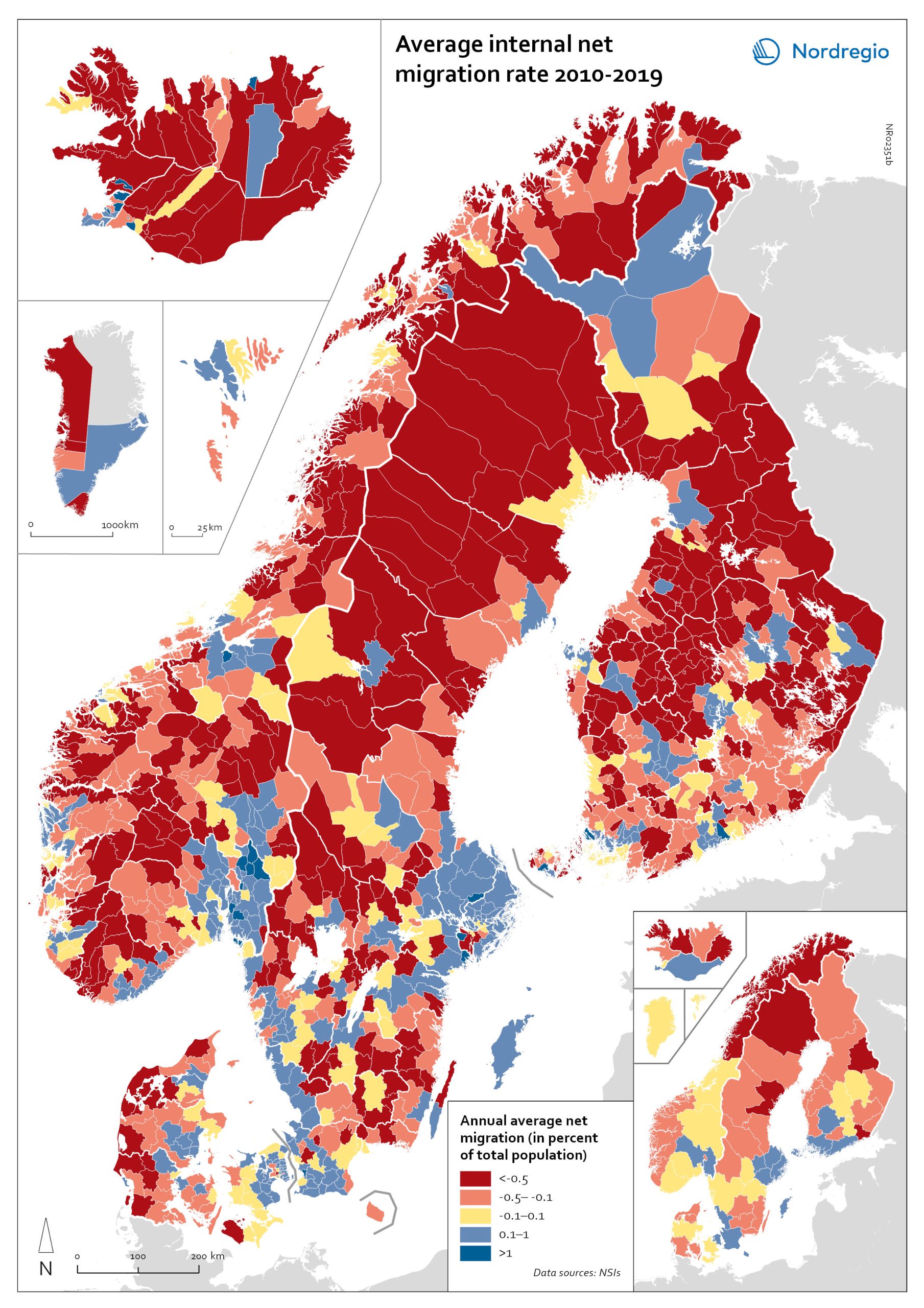

Net internal migration rate, 2010-2019

The map shows the annual average internal net migration in 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2020. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

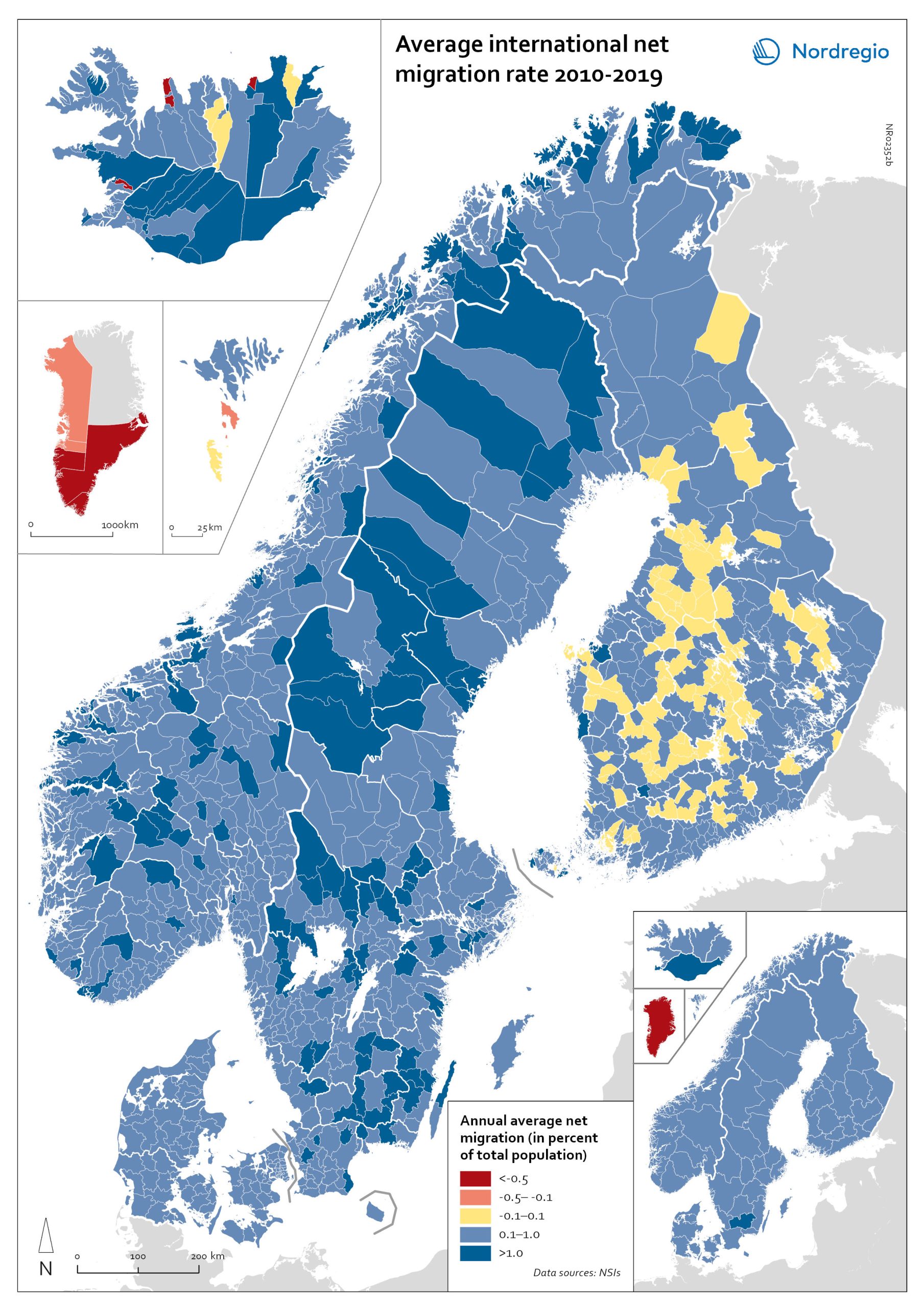

Net international migration rate, 2010–2019

The map shows the annual average international net migration from 2010 to 2019. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2020. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

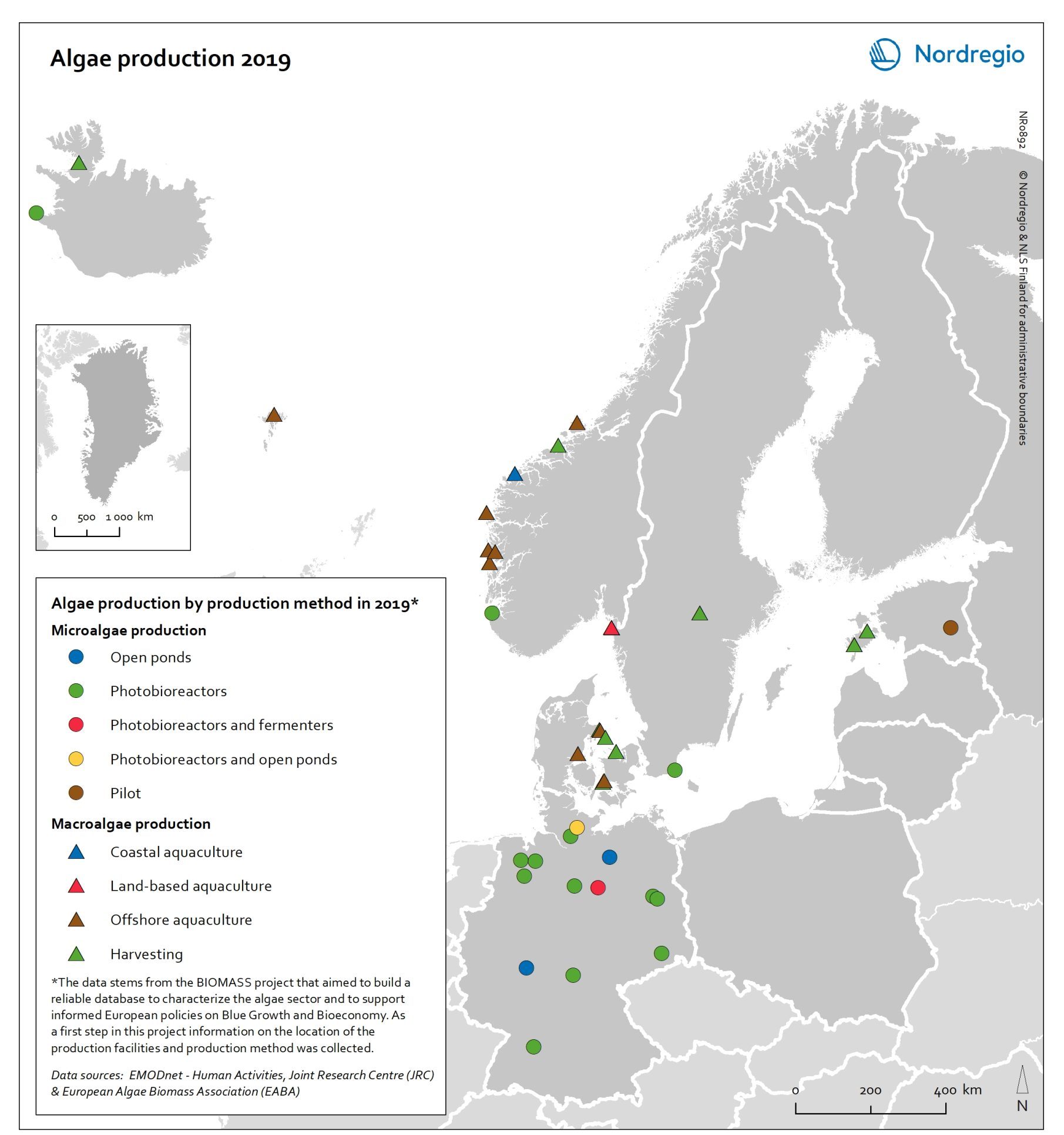

Algae production in 2019

This map shows location of algae production by production method in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2019 Algae and seaweeds are gaining attention as useful inputs for industries as diverse as energy and human food production. Aquatic vegetation – both in the seas and in freshwater – can grow at several times the pace of terrestrial plants, and the high natural oil content of some algae makes them ideal for producing a variety of products, from cosmetic oils to biofuels. At the same time, algae farming has added value in potential synergies with farming on land, as algae farms utilise nutrient run-off and reduce eutrophication. In addition, aquatic vegetation is a highly versatile feedstock. Algae and seaweed thrive in challenging and varied conditions and can be transformed into products ranging from fuel, feeds, fertiliser, and chemicals, to third-generation sugar and biomass. These benefits are the basis for seaweed and algae emerging as one of the most important bioeconomy trends in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea region. The production of algae for food and industrial uses has hence significant potential, particularly in terms of environmental impact, but it is still at an early stage. The production of algae (both micro- and macroalgae) can take numerous forms, as shown by this map. At least nine different production methods were identified in the region covered in this analysis. A total of 41 production sites were operating in Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Germany, and Sweden. Germany has by far the most sites for microalgae production, whereas Denmark and Norway have the most macroalgae sites.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Others

Major immigration flows to the Nordic Region from 2010 to 2019

The map shows annual average immigration flows above 3,000 people, and the growing diversity in their countries of origin Sweden and Denmark, in particular, experienced large inflows from non-Nordic countries during the period 2010-2019, with Sweden standing out as the Nordic country with by far the largest immigrant in-flows. A large portion of these arrivals were from war-torn Syria (an annual average of almost 15,000), followed by Poland (approximately 4,500), United Kingdom, Iraq, India and Iran (around 4,000 each). Denmark experienced a smaller number of inflows above 3,000 people, compared to Sweden. The largest non-Nordic inflows to Denmark were around 5,000 people (per sending country) and included migrants from the U.S., Germany, Romania and Poland. For Norway, large non-Nordic in-flows were limited to Lithuania and Poland. Similarly, Finland had only one major inflow, from Estonia.

2021 December

- Migration

- Nordic Region

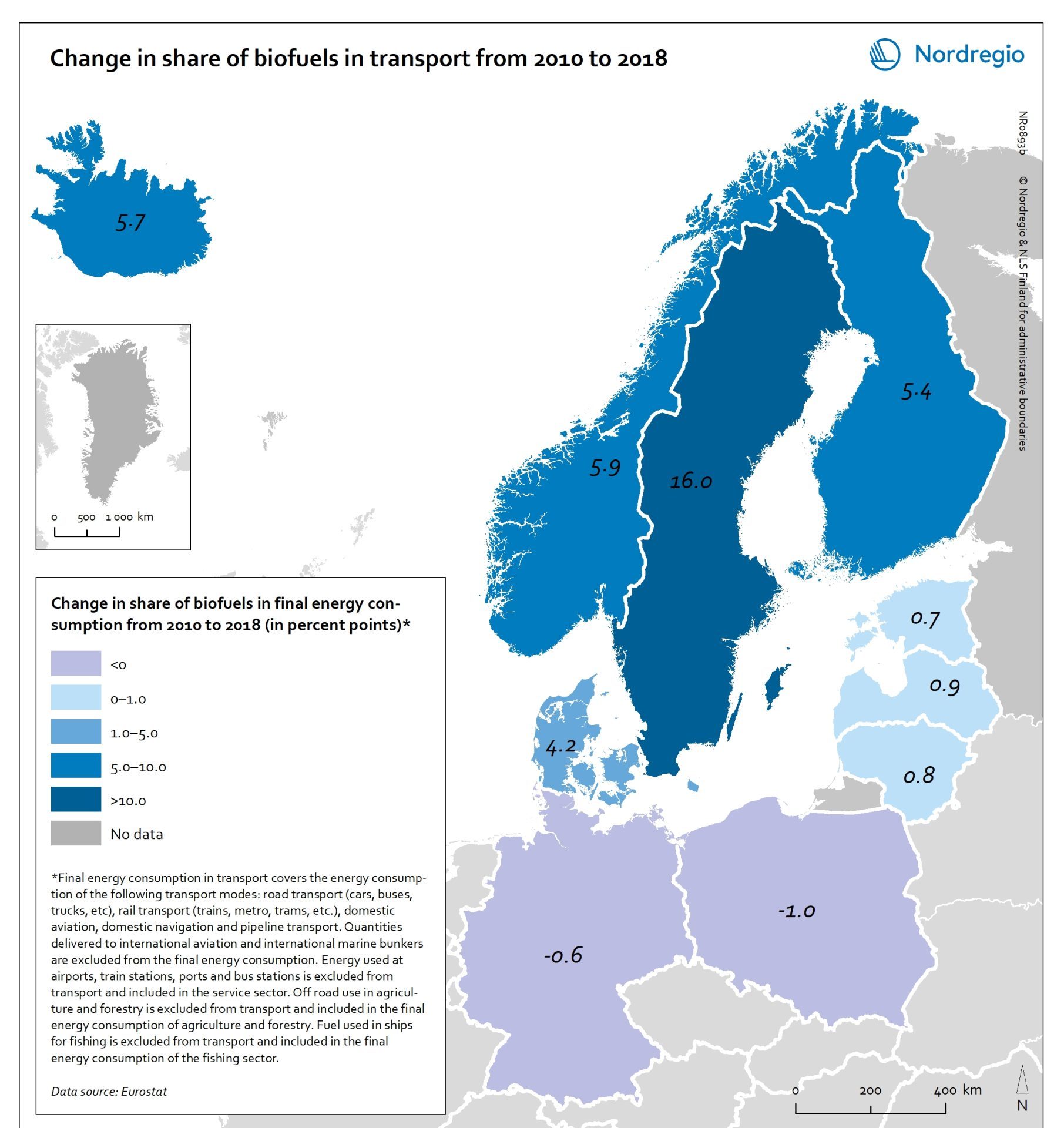

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

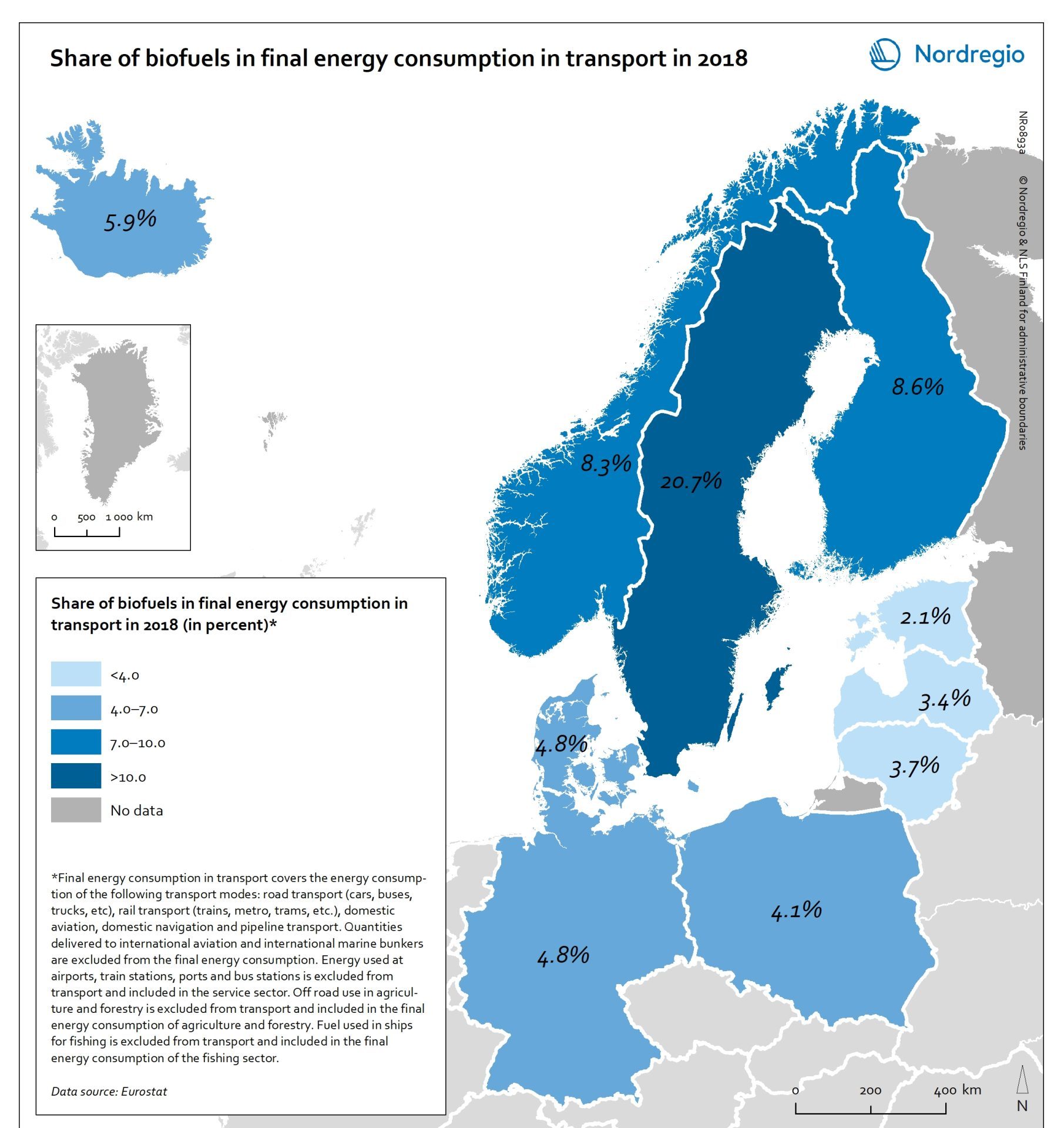

Share of biofuels in transport in 2018

This map shows the share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2018. There has been considerable political support for biofuels and in the EU, this debate has been driven by the aim of reducing dependency on imported fuels. For instance, 10 per cent of transport fuel should be produced from renewable sources. The darker shades on the map represent higher proportions, and the lighter shades reflect lower proportions. As presented by the map, only Sweden (20.7%) had reached the 10 per cent target in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Region in 2018. Both Finland (8.3%) and Norway (8.3%) were close by the target, while the other countries in the region were still lagging behind, particularly the Baltic countries.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

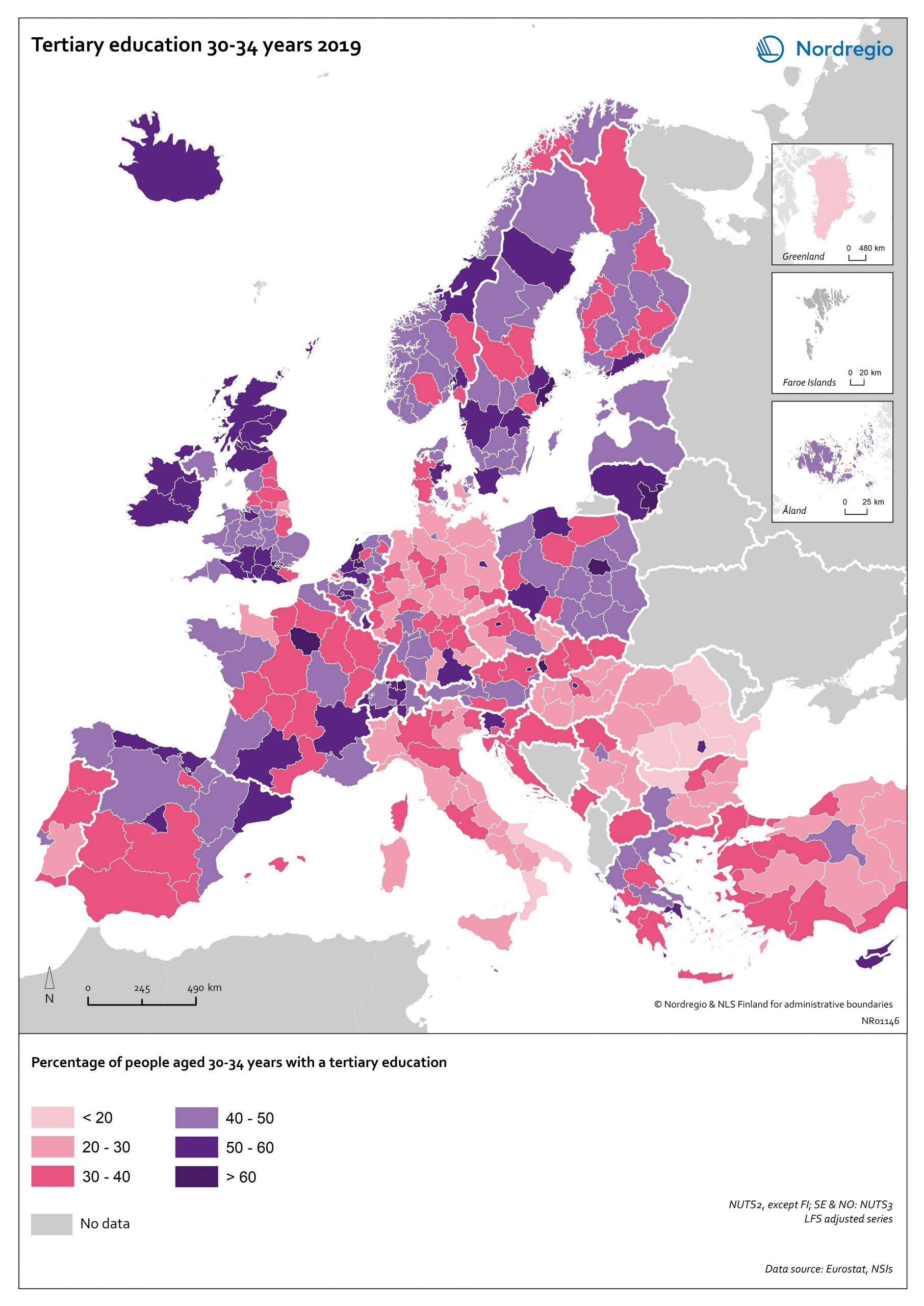

Tertiary education attainment level of 30- to 34-year-olds 2019

The map shows the proportion of the population aged 30-34 years old, who had a tertiary education at the European level in 2019. Purple shades indicate higher proportions, and pinkish shades reflect lower proportions. It is common to show the education attainment for the age group 30-34 since it is an age group where most people have finalised their studies. The focus on this age group makes it easier to see recent trends and outcomes of policies. Overall, over 40% of Europeans aged 30-34 years old had a tertiary education in 2019. Young people in the Nordic countries are among the most educated, with approximately half of 30 to 34-year-olds achieving a tertiary education across all Nordic countries. The highest proportions can be found in the capital regions. Stockholm is particularly noteworthy, with over 60% of 30 to 34-year-olds having had a tertiary education. Regions with prominent universities also stand out – for example, Skåne, Uppsala, Västerbotten and Västra Götaland (Sweden), Trøndelag (Norway) and Østjylland (Denmark).

2020 October

- Baltic Sea Region

- Demography

- Europe

- Nordic Region

- Others

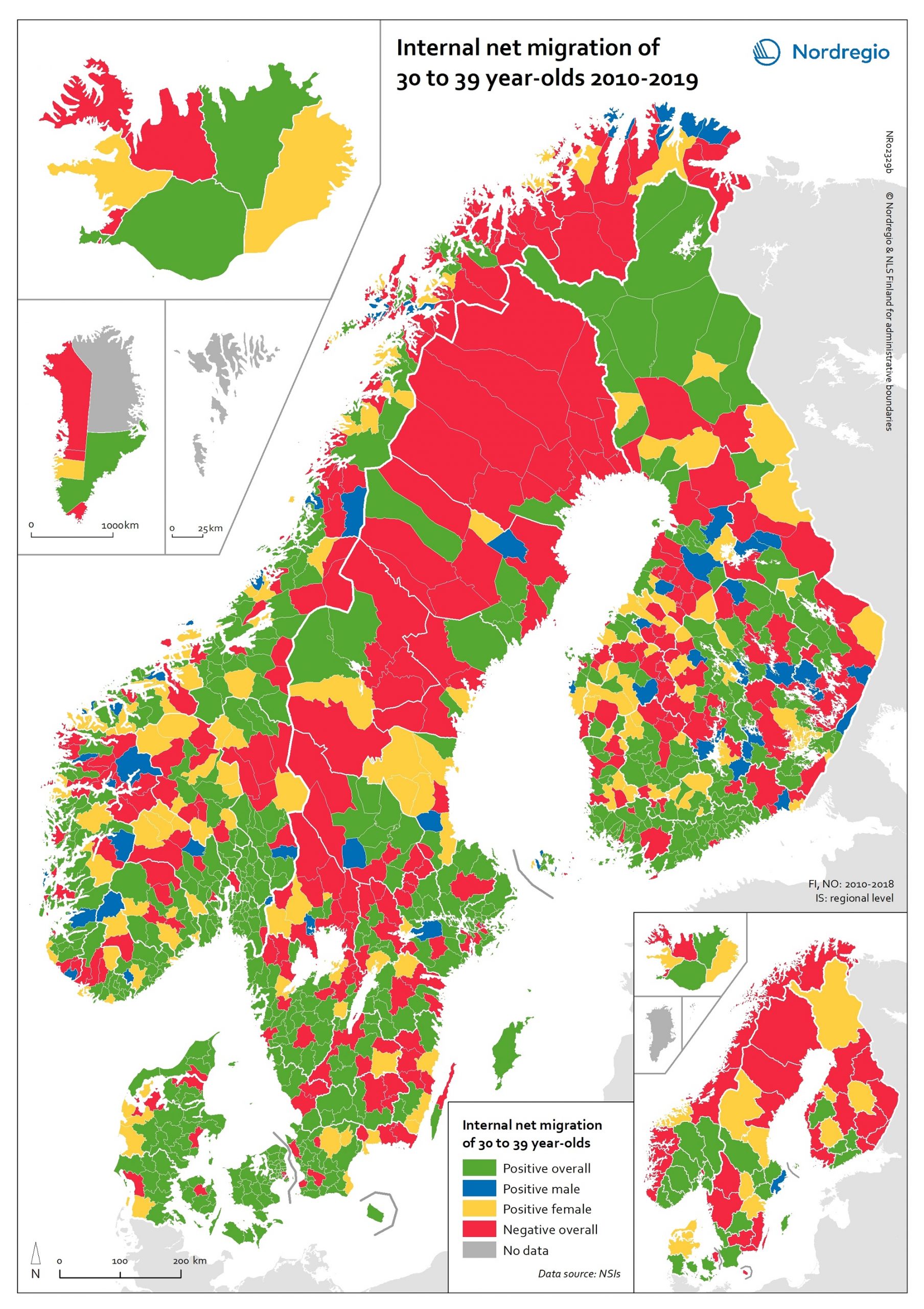

Internal net migration of 30 to 39 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows on 30 to 39-year-olds are of particular interest since it is often assumed that the future of rural regions is dependent upon their capability both to retain their populations and to attract newcomers, returning residents and second home owners. In this context, the map provides a rather positive picture, because a considerable proportion of rural municipalities have experienced positive net migration among females, males, or both sexes across all the Nordic countries. Even so, there is negative net migration among both females and males in many municipalities in northern Sweden, north-eastern Norway and eastern Finland, in addition to several inland municipalities within these countries. Interestingly, there is negative net migration among both sexes across all the capital city municipalities of the Nordic Region. According to the regional map, the capital city regions of Denmark, Iceland and Norway all experienced negative net migration of young people aged 30-39 years between 2010 and 2019. The capital city region of Sweden experienced positive net migration of males and negative net migration of females while the capital city region of Finland experienced positive net migration overall. Despite the majority of peripheral regions experiencing negative net migration of 30 to 39-year-olds during the time period studied, there are also several interesting examples of rural regions which experienced positive female net migration, for example Nordjylland (Denmark), Pohjois-Savo (Finland), Austurland (Iceland), Møre og Romsdal (Norway), and Jämtland (Sweden).

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

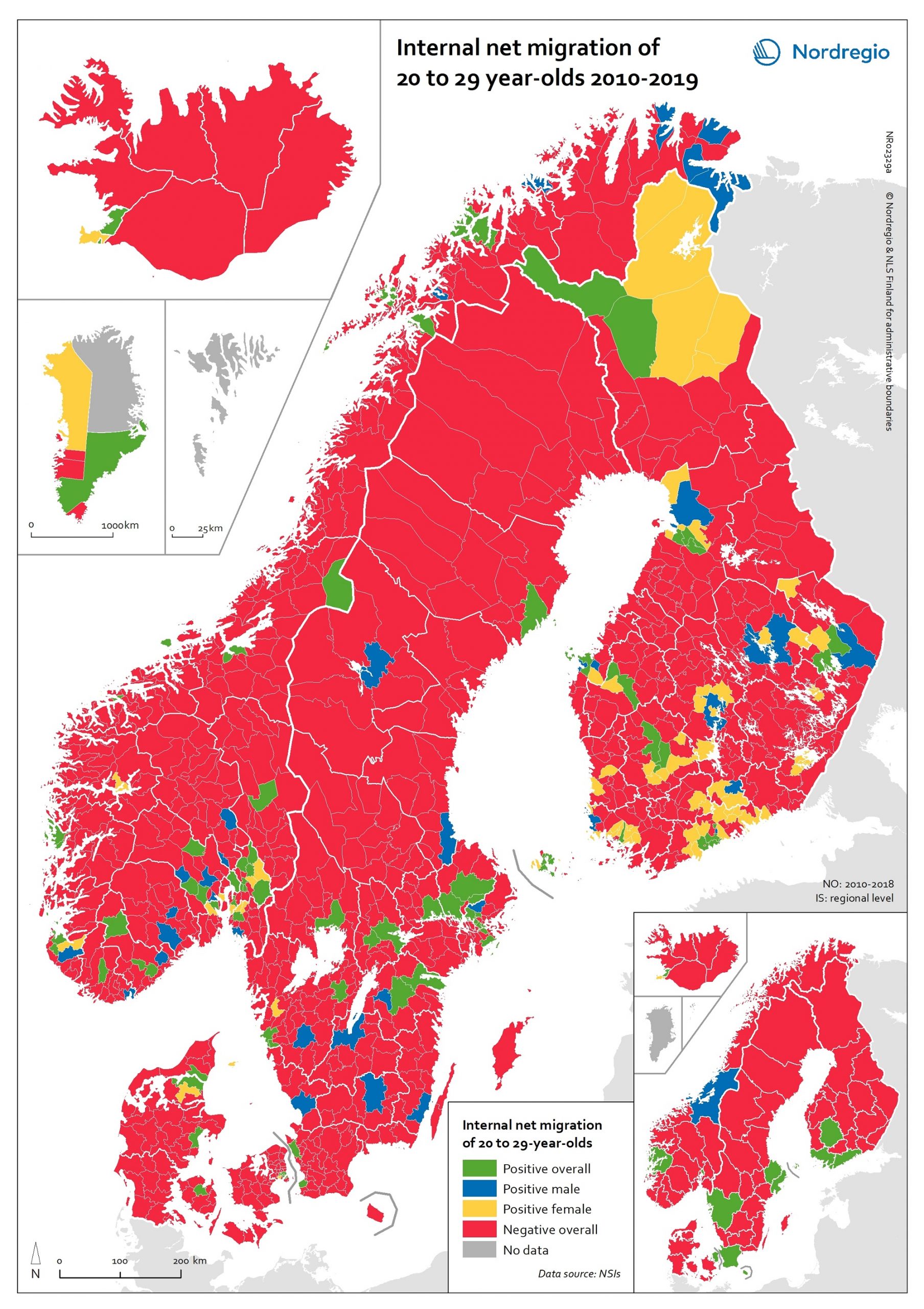

Internal net migration of 20 to 29 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows of 20 to 29-year-olds are of interest since there is a particularly high level of internal migration among young adults across the Nordic countries compared to other EU countries. While the map shows that the great majority of municipalities experience negative net migration of young adults in favour of a few functional urban areas and some larger towns, it is possible to observe a number of exceptions to this general rule. The rural municipalities of Utsira, Moskenes, Valle, Smøla, Ballangen and Lierne in Norway have the highest positive net migration rates both for men and women. There are also positive net migration rates for males and females in the peripheral municipalities of Jomala, Kittilä, Lemland and Finström in Finland and Åland. There is positive male net migration but negative female net migration in Gratangen, Loppa, Gamvik, Drangedal and a few other Norwegian rural municipalities, plus Mariehamn in Åland, while several municipalities in remote areas of Finland have positive female net migration but negative male net migration. Some of these patterns may be related to specialised local labour markets, such as fisheries in Loppa, or recreational tourism in Kittilä. In general, the pattern of net migration among young adults is more diverse in Finland (where 72.0% of all municipalities have negative net migration), compared with 84.6% in Norway, 88.9% in Denmark and 89.0% in Sweden. However, it is important to remember that Danish, Finnish and Norwegian municipalities are smaller in size…

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Internal net migration as percentage of population 2010–2018

This map shows annual average internal net migration rate at the municipal and regional level in 2010-2018. The map shows the percentage change from internal migration for the period 2010 to 2018. Internal or domestic migration refers to migration between municipalities and regions within the same country. The blue areas on the map show municipalities/regions with positive internal net migration (i.e. more people arriving than departing), the red areas show municipalities/regions with negative internal net migration (i.e. more people departing than arriving) and the yellow areas show municipalities/regions with balanced internal net migration rates (i.e. comparable numbers of people arriving and departing). The trend revealed is that internal migration movements are directed towards larger city regions, with many rural periphery regions losing people. The loss of people in some of these regions is felt especially acutely because of the age selectivity of migration, with young people leaving in large numbers, accelerating the ageing of the population structure in regions with high out-migration. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Internal and international net migration 2010-2018

This map shows internal and international net migration in 2010-2018. The map shows the combination of domestic migration (left-hand bar) and international migration (right-hand bar), with red indicating net out-migration and green indicating net in-migration, for the 66 regions within the Nordic Region in the period 2010 to 2018. The size of the bar indicates the size of the net flows. All regions have had positive international migration since 2010, which is not surprising given the size of the international migration flows into the Nordic Region in recent years. Overall in the Nordic Region, there were either domestic migration losses and international migration gains or gains from people moving both from elsewhere in the country and from abroad. The gains from international migration far exceeded those of internal migration in almost all regions that experienced net gains from both streams. Due to these different patterns of internal and international migration, nearly all regions are becoming much more diverse in terms of the size of foreign-born populations. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Total population change by main component 2010-2018

This map shows total population change by main component at the municipal and regional level in 2010-2018. The two components of population change are natural change and net migration. As the map shows, all regions in Denmark, Norway and Sweden experienced population increase due to either a combination of natural increase and net migration or through net migration alone between 2010-2018. In Iceland, all regions experienced both positive natural increase and positive net migration, except for Vestfirðir and Norðurland vestra, which experienced population decline despite experiencing more births than deaths over the period. The regional picture in Finland was more varied, with population decline most pronounced in the east and the north. At the municipal level, the highest overall population growth can be found mostly in the capital regions and bigger cities (e.g. Tampere and Turku in Finland), Central Jutland (Denmark), coastal areas of Norway, southern Iceland, southern Sweden, the northern municipalities of the Faroe Islands and Sermersooq Municipality (Greenland), which contains the capital of Nuuk. The highest overall population decline can be found mostly in the western and southern parts of Denmark, the majority of Finnish municipalities and most inland municipalities in northern Sweden. While the map shows a snapshot of population change for one decade, these trends of population increase in urban regions and municipalities and decline and ageing in periphery regions and municipalities have been underway for some time and are expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Early leavers from education and training 2016

This map shows the percent of early school leavers in the Nordic Region (NUTS 2 level) and Baltic states in 2016, calculated as the total number of individuals aged 18-24 having a lower secondary education as the highest level attained and not being involved in further education or training. The numbers in each region indicate the proportion of females per 100 males. The yellow/red shading indicates the percent of early school leavers in 2016. The lighter the colour the lower the percentage of early school leavers in 2016. The grey colour indicates no data. Early school leaving is of concern in the Nordic Region to varying degrees. From a pan-European perspective, the Danish (7.2%), Swedish (7.4%) and Finnish (7.9%) averages all fall below the EU average (10.7%) and are in line with the Europe 2020 target of below 10%. The Norwegian average (10.9%) remains slightly above the target but is comparable to the EU average. The average rate of early school leaving in Iceland (19.8%) is substantially higher than the other Nordic countries and the EU average. There is both a spatial and a gender dimension to this problem. The spatial dimension of early school leaving is highlighted in this map, which shows rates of early school leaving in the Nordic Region at the NUTS 2 level. The map highlights the comparatively high rates in Norway, particularly in the north. It is worth noting that, although still high in a Nordic comparative perspective, early school leaving rates have decreased in all Norwegian regions since 2012. Rates are also high in Greenland, with a staggering 57.5% of young people aged 18–24 years who are not currently studying and who have lower secondary as their highest level of educational attainment. The map also shows the gender dimension of early school leaving, with…

2018 February

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Gross Regional Product per capita in million PPP 2015

This map shows the gross regional product per capita in million purchasing power parity (PPP) in all Nordic and Baltic Regions in 2015. The green tones indicate regions with a gross regional product per capita above the EU28 average. The darker the tone the higher the gross regional product per capita. The brown/yellow shading indicates regions with a gross regional product per capita below the EU28 average. The darker the tone the lower the gross regional product per capita. In economic development terms, the Nordic Region continues to perform well in relation to the EU average. Urban and capital city regions still show high levels of GDP per capita reflecting the established pattern throughout Europe. Stockholm, Oslo, Helsinki, Copenhagen and the western Norwegian regions are among the wealthiest in Europe, again confirming that the capital regions and larger cities are the strongest economic centres in the Nordic Region. In addition to these urban regions, some others also display high levels of GRP per capita. What is interesting is that in the aftermath of the economic crisis some second-tier city regions, such as Västra Götaland with Gothenburg in Sweden, are now also displaying fast growth rates as indeed are some less metropolitan regions in the western part of Denmark. These regions display GRP per capita levels which correspond to, or even exceed, those of most metropolitan regions in Europe. most of the central and eastern parts of Finland remain below the EU average.

2018 February

- Baltic Sea Region

- Economy

NEET rate for young people 18-25 years in 2016

Share of young people aged 18-25 years neither in employment nor in education and training in 2016 There are a range of reasons why a young person may become part of the “NEETs” group, including (but not limited to): complex personal or family related issues; young people’s greater vulnerability in the labour market during times of economic crisis; and the growing trend towards precarious forms of employment for young people. Successful reengagement of these young people with learning and/or the labour market is a key challenge for policy makers and is vital to reducing the risk of long-term unemployment and social exclusion later in life. The map highlights two Polish regions, Podkarpackie and Warminsko-Mazurskie, as having the highest NEET rates in the BSR. High rates can also be found in several other Polish regions as well as the Northern and Eastern Finland Region. The lowest NEET rates in the Baltic Sea Region can be found in the Norwegian Capital Region, followed by several regions in Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

2017 June

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

Youth unemployment rate in 2016

The map highlights two Polish regions, Podkarpackie and Lubuskie, as having the highest youth unemployment rates in the BSR. Several other regions in Poland, along with regions in Northern Finland, Central Sweden and the southernmost Swedish region of Skåne, have also been rather severely hit by youth unemployment. The lowest youth unemployment rates can be found in several Russian regions, among them St. Petersburg, and in regions in Northern Germany and Northern Norway.

2017 June

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Tertiary education among working-age population, change 2010-2015

The Nordic countries, as well as Estonia and Lithuania, have had among the highest levels of tertiary education in Europe in recent years. This map demonstrates that many regions, particularly those in Poland, are catching up. Several Lithuanian and Latvian regions have also had high rates of positive change between 2010 and 2015. The most modest growth rates, between 0 and 1.5 percent change, were experienced in two Estonian regions, one in Denmark and one in Northern Germany. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Brandenburg, in North-Eastern Germany, were the only regions within the Baltic Sea Region to experience a decrease in the share of working-age persons with tertiary level education from 2010-2015.

2017 March

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region