118 Maps

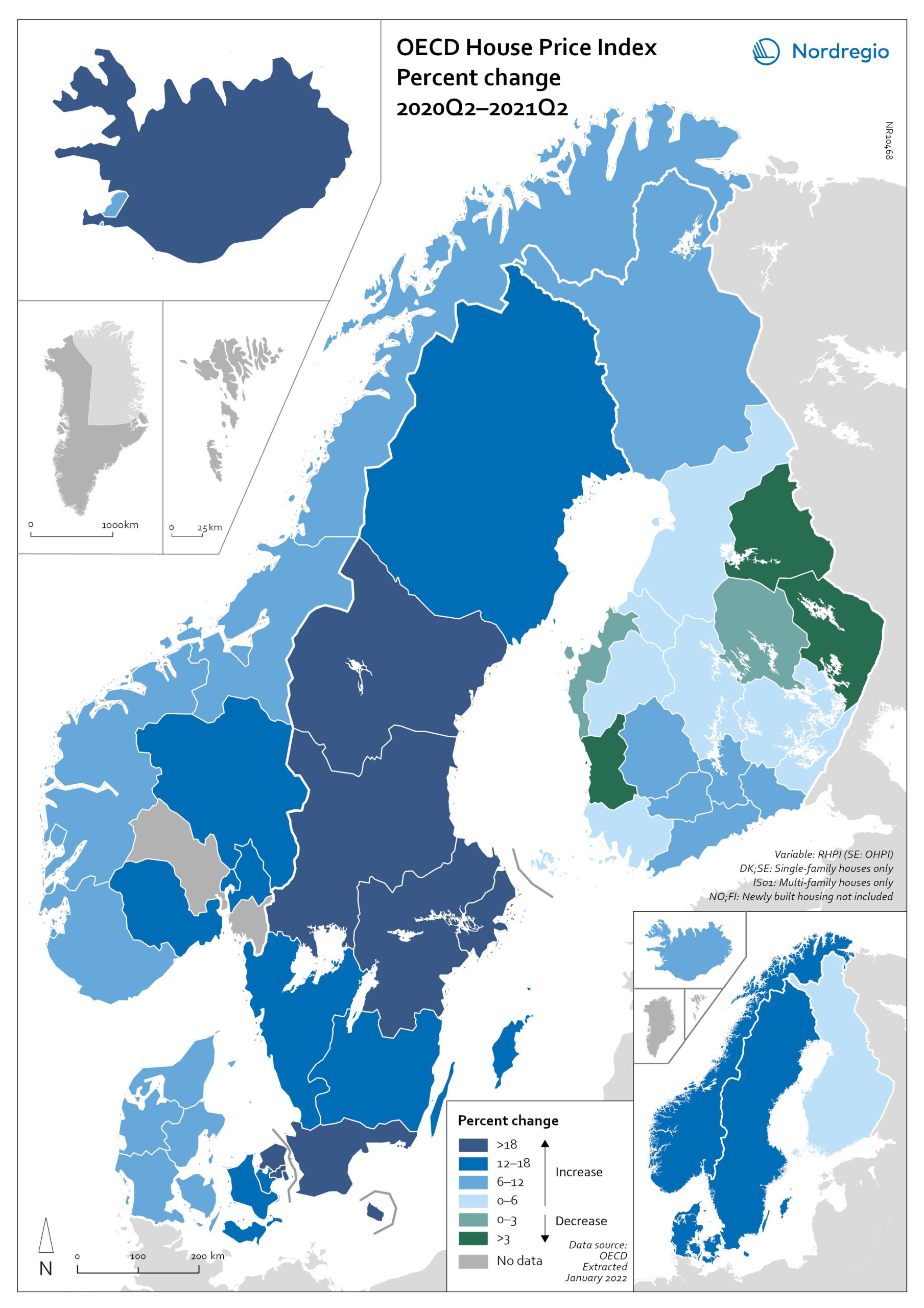

OECD House Price Index. Change 2020Q2–2021Q2

The map shows the relative change of the OECD House Price Index from Q2 2020 to Q2 2021. The map shows that the price development was not uniform within the countries. Iceland recorded the largest price increases overall, with the most marked price increases found outside of the capital region. All Swedish regions recorded increases above 20%, with the highest increases in the Stockholm and Malmö regions. All Norwegian regions showed price increases, though to a lesser extent than Swedish regions in most cases. In Denmark, Bornholm, Sjælland and the rural islands of Lolland and Falster recorded relatively high price increases, although many rural areas developed from low absolute prices in 2020. Finland was the only country where some regions saw property prices decrease. Moderate increases were still observed in some of the southern regions, where the major cities are located, and in the north.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

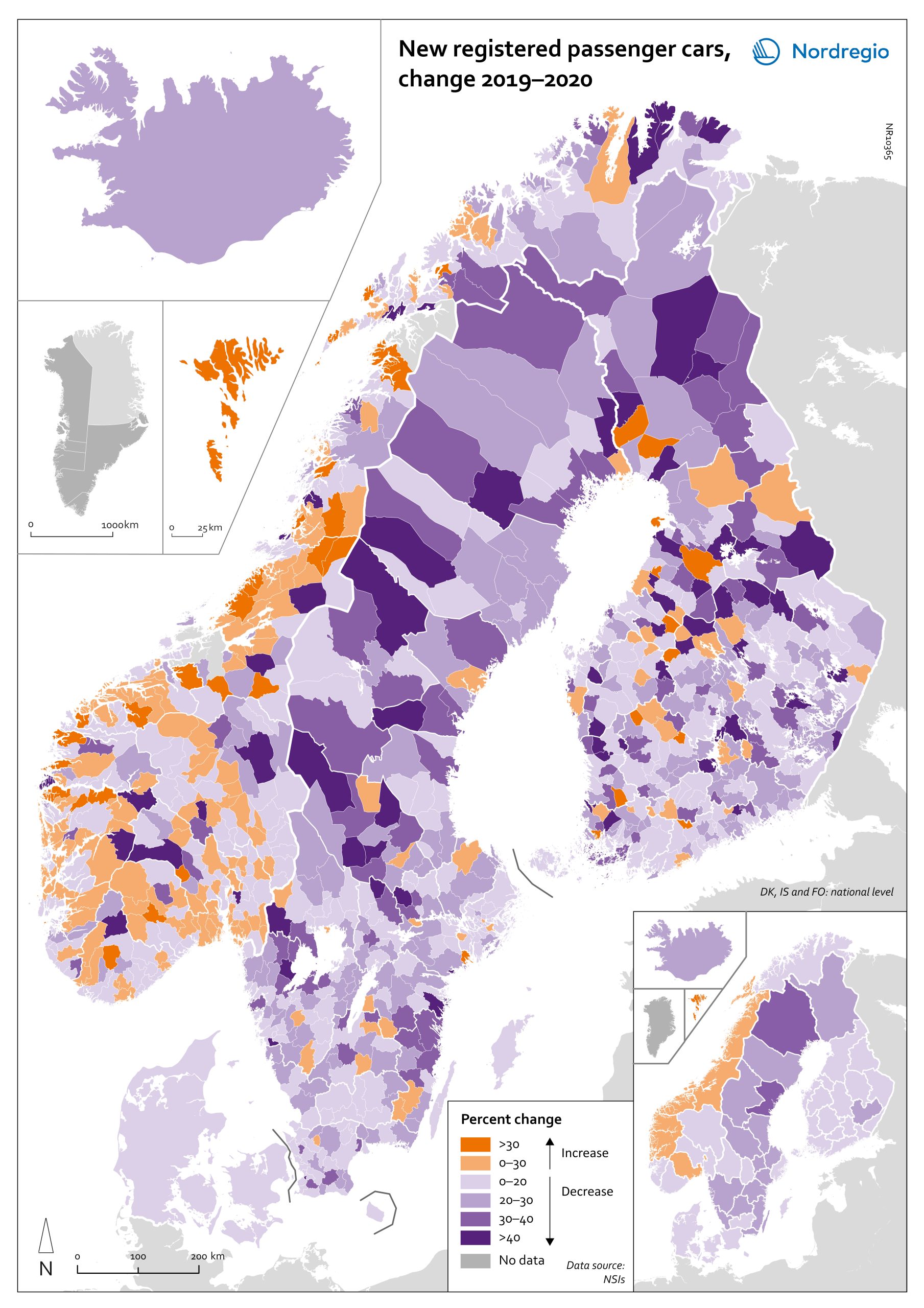

Change in new registered cars 2019-2020

The map shows the change in new registered passenger cars from 2019 to 2020. In most countries, the number of car registrations fell in 2020 compared to 2019. On a global scale, it is estimated that sales of motor vehicles fell by 14%. In the EU, passenger car registrations during the first three quarters of 2020 dropped by 28.8%. The recovery of consumption during Q4 2020 brought the total contraction for the year down to 23.7%, or 3 million fewer cars sold than in 2019. In the Nordic countries, consumer behaviour was consistent overall with the EU and the rest of the world. However, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Åland, and Denmark recorded falls of 22%–11% – a far more severe decline than Norway, where the market only fell by 2.0%. The Faroe Islands was the only Nordic country to record more car registrations, up 15.8% in 2020 compared to 2019. In Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, there were differences in car registrations in different parts of the country. In Sweden and Finland, the position was more or less the same in the whole of the country, with only a few municipalities sticking out. In Finland and Sweden, net increases in car registrations were concentrated in rural areas, while in major urban areas, such as Uusimaa-Nyland in Finland and Västra Götaland and Stockholm in Sweden, car sales fell between 10%–22%. Net increases in Norway were recorded in many municipalities throughout the whole country in 2020 compared to 2019.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Transport

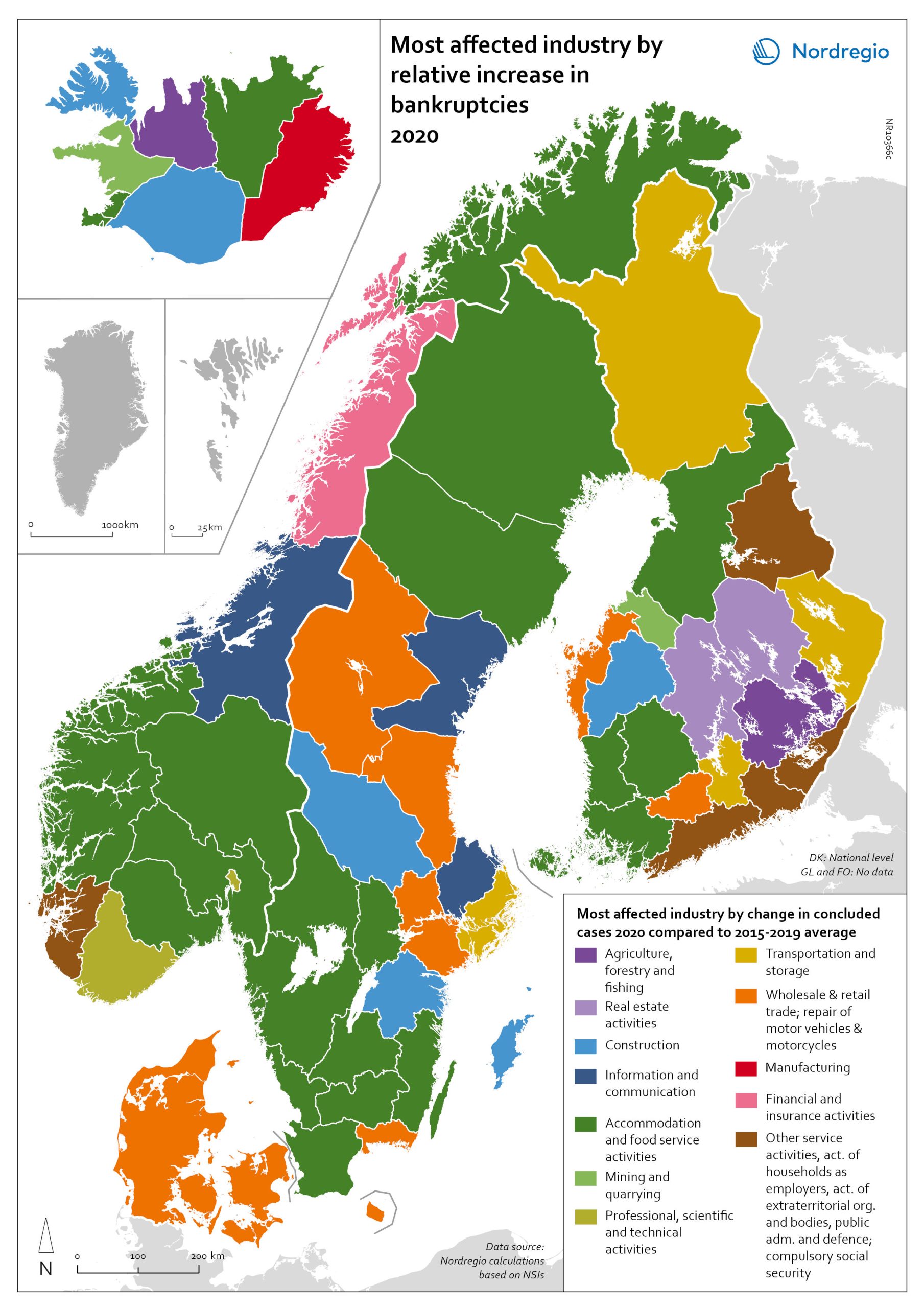

Bankruptcies in 2020 by industry and region

The map shows the most affected industry by relative increase in concluded business bankruptcies 2020 compared to 2015–2019 average. Regional patterns in business failures are linked to factors ranging from the effectiveness of the measures adopted by the various governments to the exposure of regional economies to vulnerable sectors. Regions with higher numbers of bankruptcies tend to reflect the concentration of economic activity in sectors particularly affected by the pandemic. It comes as little surprise that Accommodation and food service activities were the industries with the largest increase in business bankruptcies in 2020 compared to the 2015–2019 baseline. In the Nordic Region as a whole, the number rose by 28.6%. This pattern is also discernible at the regional level. Hotels and restaurants were the activities with the biggest increase in the number of bankruptcies in a significant number of Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish regions. Other sectors suffering higher-than-average numbers of business bankruptcies are service industries, particularly those requiring closer social interaction, like Education (16.5% increase), Other service activities (12.0% increase) and Administrative and support service activities (7.9% increase). The logistics sector was also greatly affected, with major impact localised around logistics centres and transport nodes in the different countries. In the capital regions of Oslo, Stockholm and Helsinki, Transportation and storage was the sector with the largest increase in bankruptcies. Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles was the industry to suffer the most in Denmark and several Finnish and Swedish regions.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

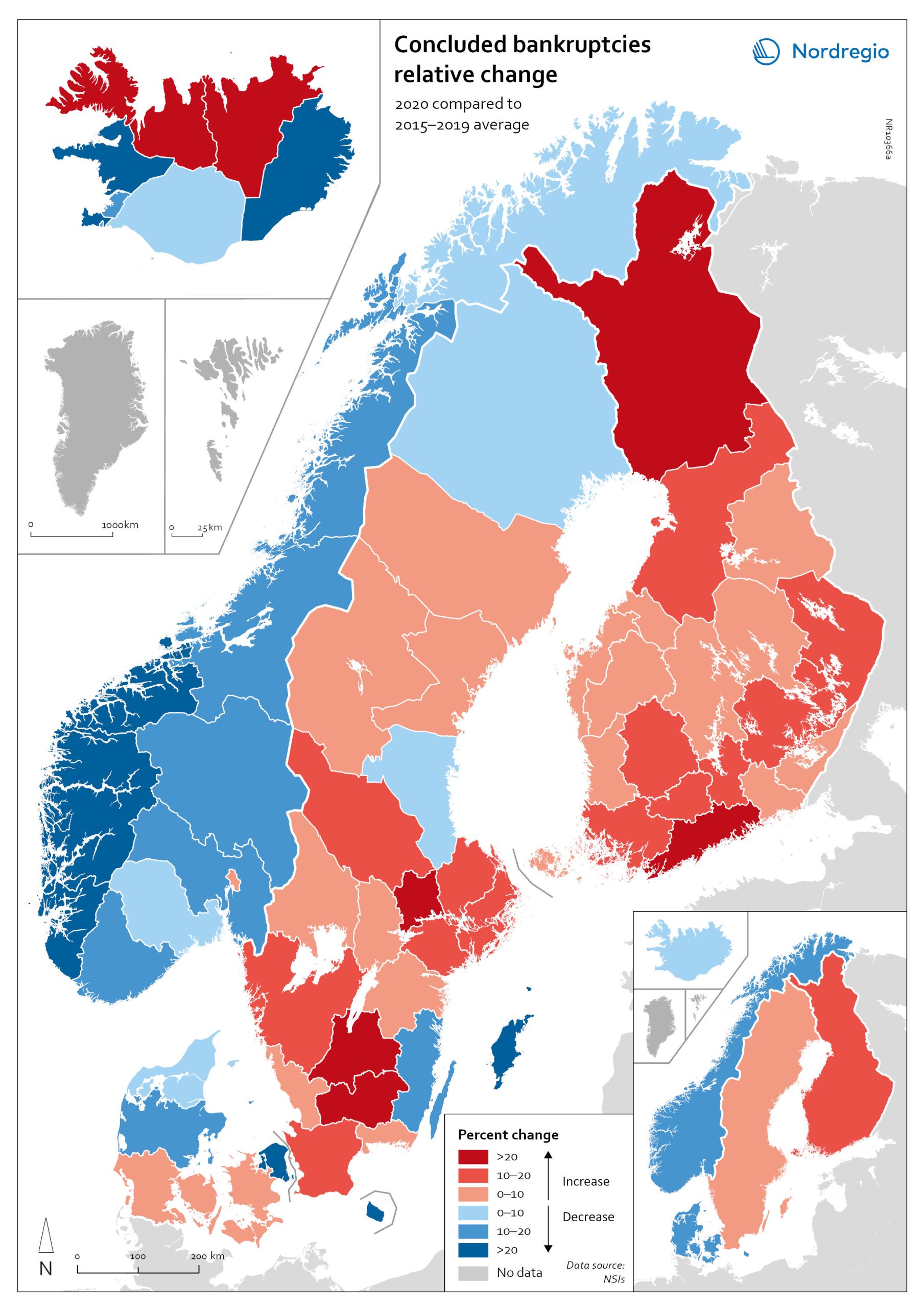

Relative change in the number of business bankruptcies

The map shows the relative change in the number of concluded business bankruptcies by region, 2015–2019 average compared to 2020. At sub-national levels, the distribution of business bankruptcies does not show a clear territorial pattern. In Iceland and Denmark, businesses in the most urbanised areas, including the capital regions, seem to have been those that benefited most from the economic mitigation measures (-23.9% in Höfuðborgarsvæðið and -24.4% in Region Hovedstaden). By contrast, Oslo is the only Norwegian region where there were more business bankruptcies in 2020 compared to the 2015–2019 baseline (1.9% increase). Most Norwegian regions did, in fact, have fewer bankruptcies in 2020, particularly in the western regions. One plausible explanation for this could be that the number of business failures during the baseline period was especially high in western Norway due to the fall in oil prices in 2014–2015. In Sweden the situation is even more mixed. Here, businesses in urban areas seem to have been more exposed to the distress caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The most urbanised regions in the Stockholm-Gothenburg-Malmö corridor registered a greater increase in liquidations (Jönköping, Kronoberg and Södermanland regions saw surges of around 20%). However, predominantly rural regions in Sweden, such as Västerbotten and Jämtland, also recorded higher numbers of bankruptcies than average (9.8% and 8.8% increase, respectively). In Finland, the impact was greater in Lapland (26.9%) and around Helsinki (Uusimaa, 25.9%) than in the central parts of the country. Åland also experienced a moderate rise in business bankruptcies in 2020 (4.0%), mostly related to the tourism sector.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

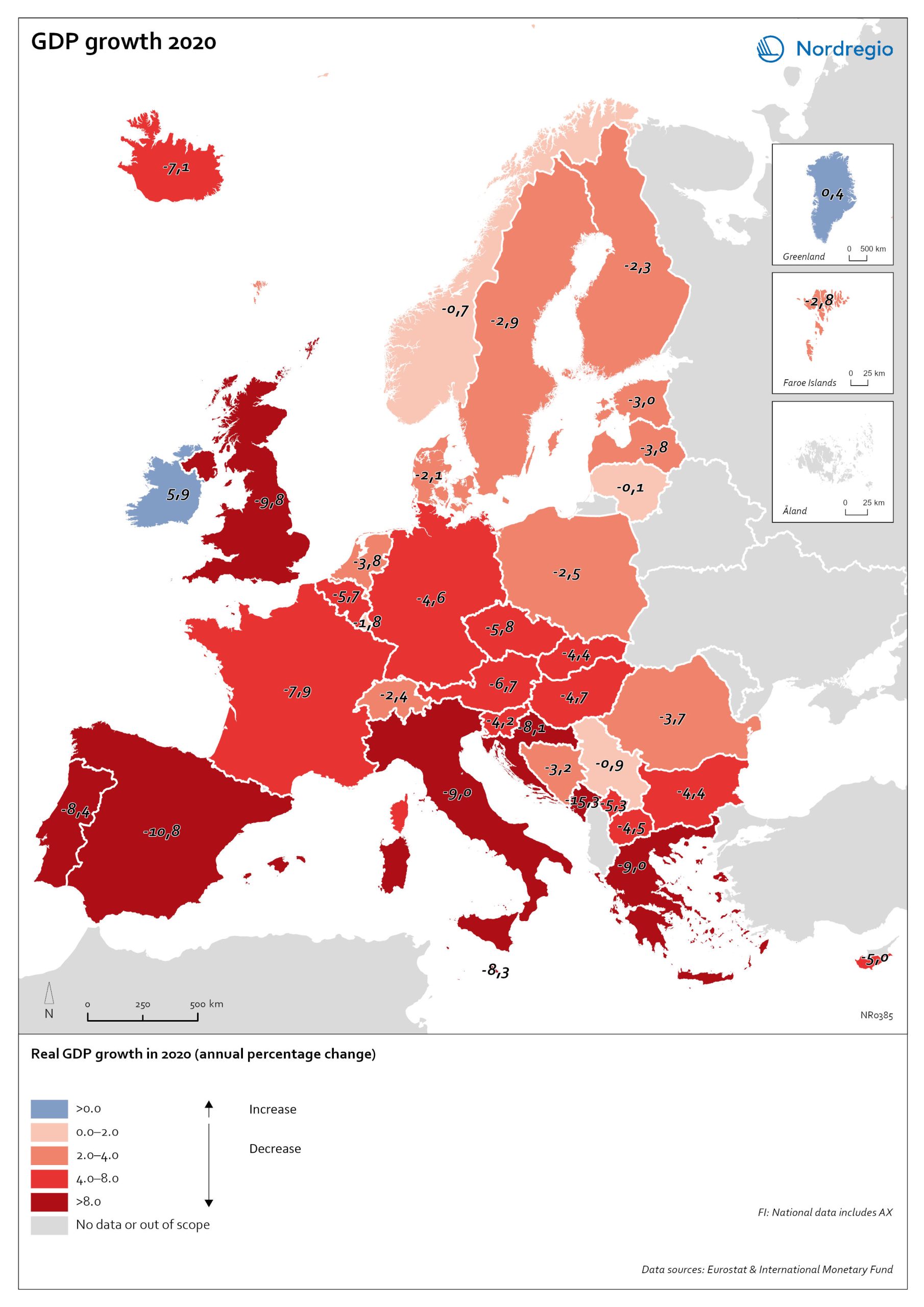

Population change by component 2010-2019

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

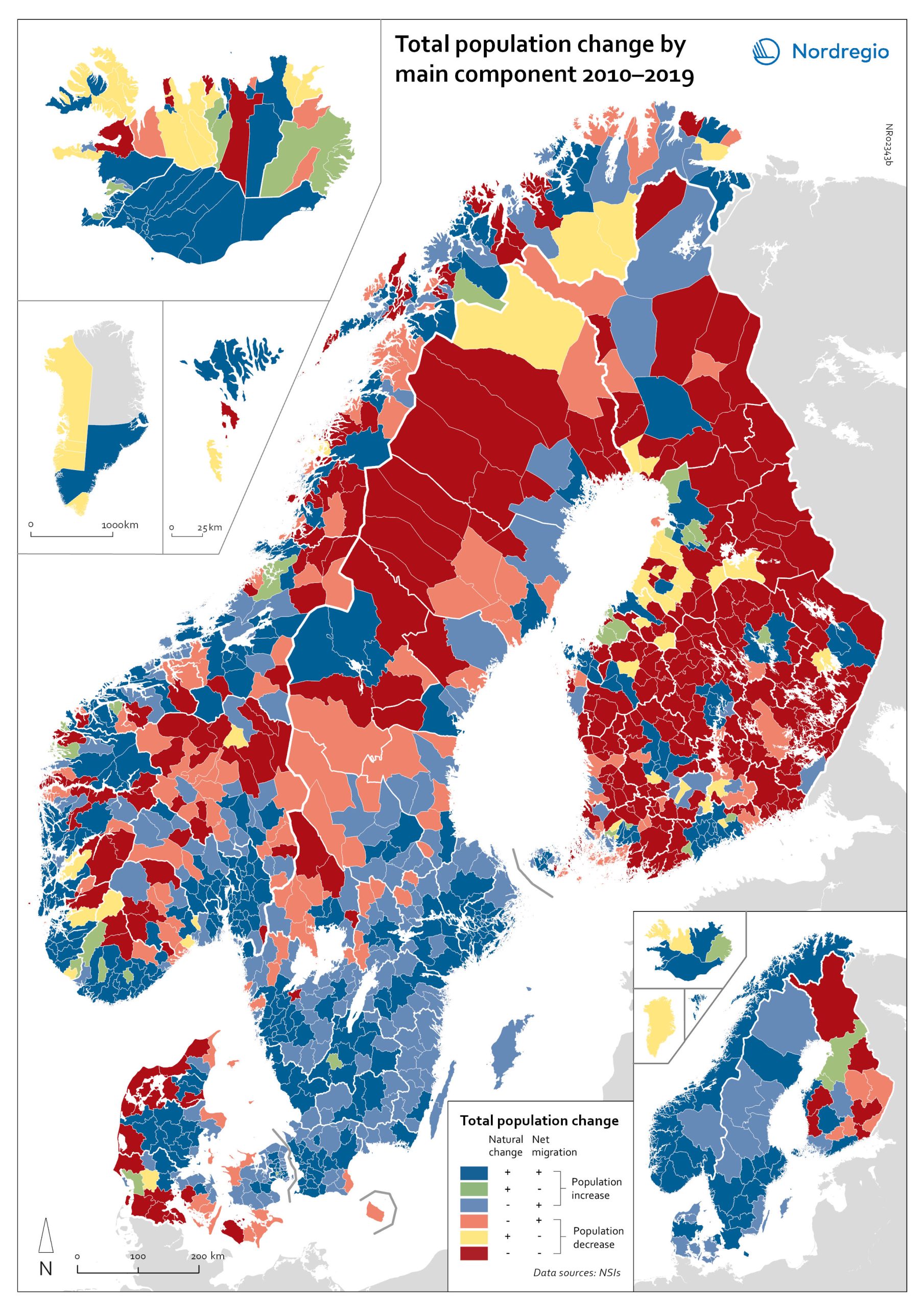

Net internal migration rate, 2010-2019

The map shows the annual average internal net migration in 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2020. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

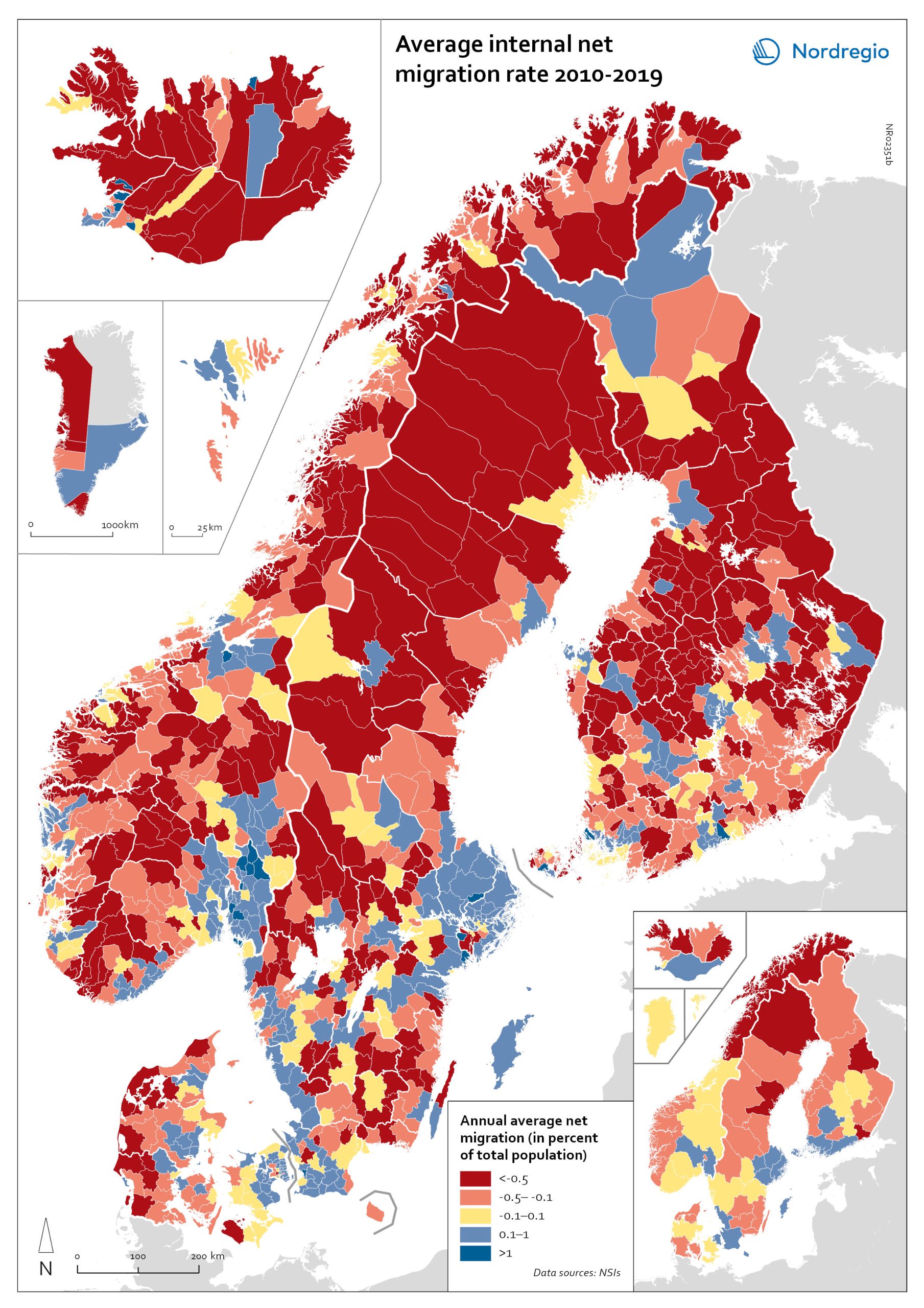

Net international migration rate, 2010–2019

The map shows the annual average international net migration from 2010 to 2019. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2020. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

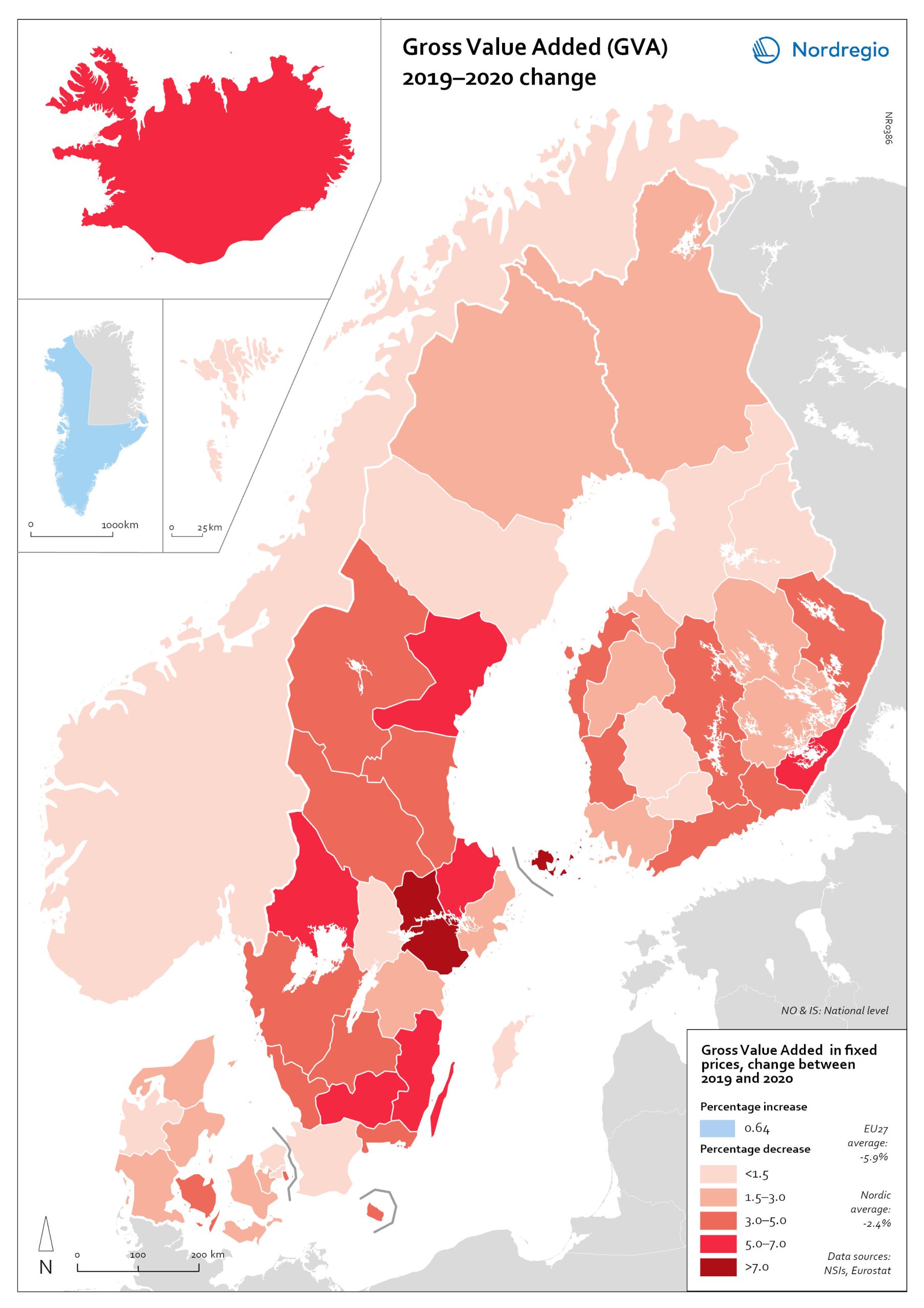

Gross Value Added (GVA) change 2019-2020

The map shows the change in regional Gross Value Added (GVA) from 2019 to 2020 (in fixed prices). As shown in the map, aggregated production levels, in terms of Gross Value Added (GVA), contracted in nearly all of the Nordic regions between 2019 and 2020. In general, the variability was comparatively smaller within each country than it was between countries, even when comparing regions with similar economic profiles from different countries. On average, the impact was greater on regions in Sweden and Finland than those in Denmark. Still, some relevant territorial patterns emerge from the changes to regional GVA shown in the map. The contraction was larger in regions with higher dependence on tourism services and hospitality (Åland and some municipalities in South Karelia, Finland, and Bornholm, Denmark), as well as on mass-market retail and logistics, particularly in the areas surrounding the capital regions (Södermanland and Västmanland in Sweden and Greater Copenhagen in Denmark). In Sweden and Finland, a remarkable regional divide can also be traced between territories specialised in transformation sectors with limited vulnerability to the impact of Covid-19, including forestry and specific types of processing (e.g. pulp, cement), like Nord Ostrobothnia, Kainuu and Pirkanmaa in Finland, and Gotland, Västerbotten and Örebro in Sweden. Aggregated output in these regions fell less than in regions with greater exposure to industrial manufacturing, like Kymenlaakso in Finland and Kronobergs in Sweden. Similarly, the impact on the financial centres in Denmark (Greater Copenhagen) and Sweden (Stockholm) was less than regions with mid-sized cities and diversified urban economies, like Vestjylland (Århus) in Denmark and Upsala in Sweden. Interestingly, the shock to the Finnish economy was greater in the Helsinki metropolitan area (-3.6% Uusimaa) than it was for the Tampere region (-0.5% in Pirkanmaa). This may be due to the relatively higher concentration…

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

Major immigration flows to the Nordic Region from 2010 to 2019

The map shows annual average immigration flows above 3,000 people, and the growing diversity in their countries of origin Sweden and Denmark, in particular, experienced large inflows from non-Nordic countries during the period 2010-2019, with Sweden standing out as the Nordic country with by far the largest immigrant in-flows. A large portion of these arrivals were from war-torn Syria (an annual average of almost 15,000), followed by Poland (approximately 4,500), United Kingdom, Iraq, India and Iran (around 4,000 each). Denmark experienced a smaller number of inflows above 3,000 people, compared to Sweden. The largest non-Nordic inflows to Denmark were around 5,000 people (per sending country) and included migrants from the U.S., Germany, Romania and Poland. For Norway, large non-Nordic in-flows were limited to Lithuania and Poland. Similarly, Finland had only one major inflow, from Estonia.

2021 December

- Migration

- Nordic Region

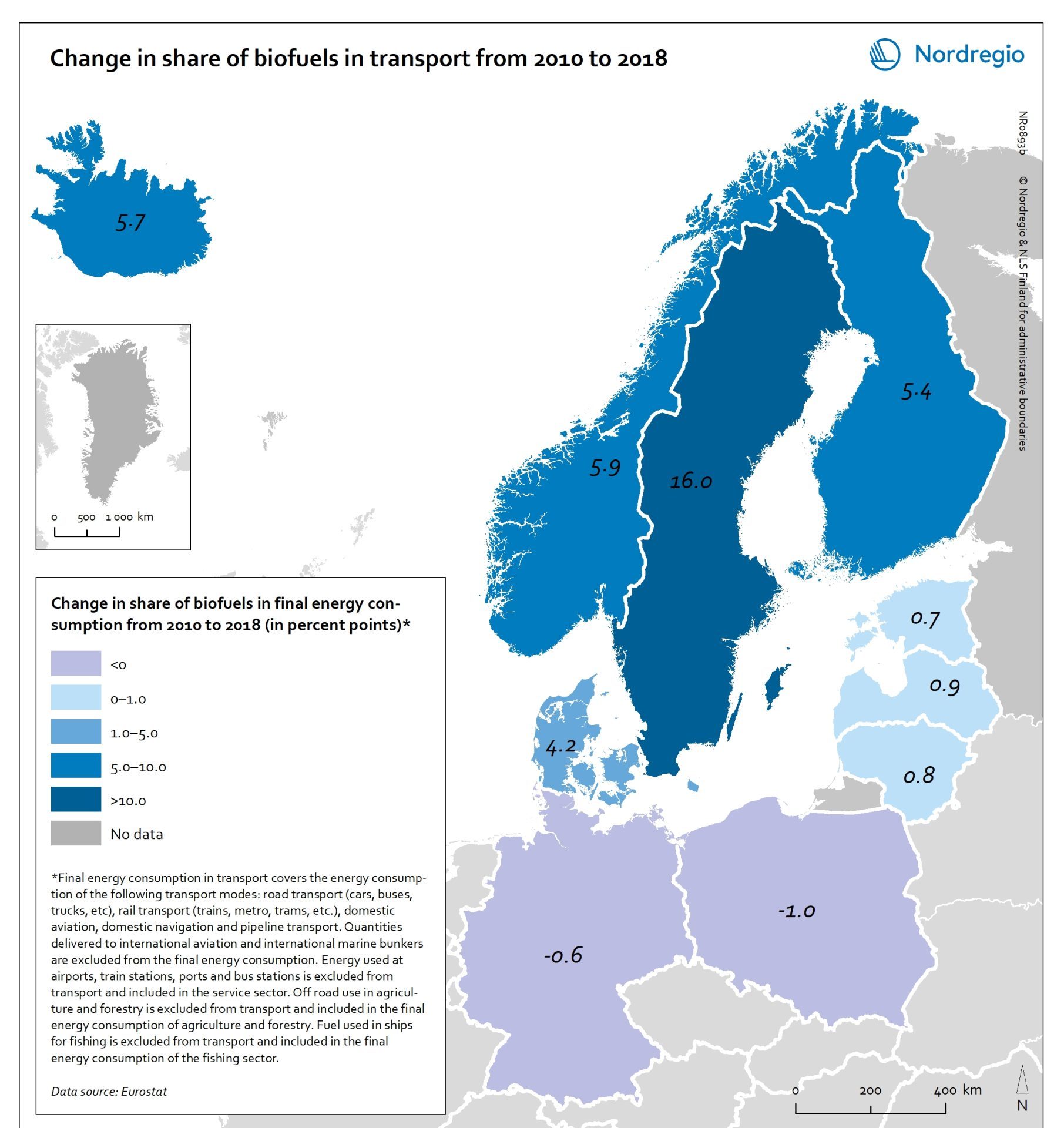

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

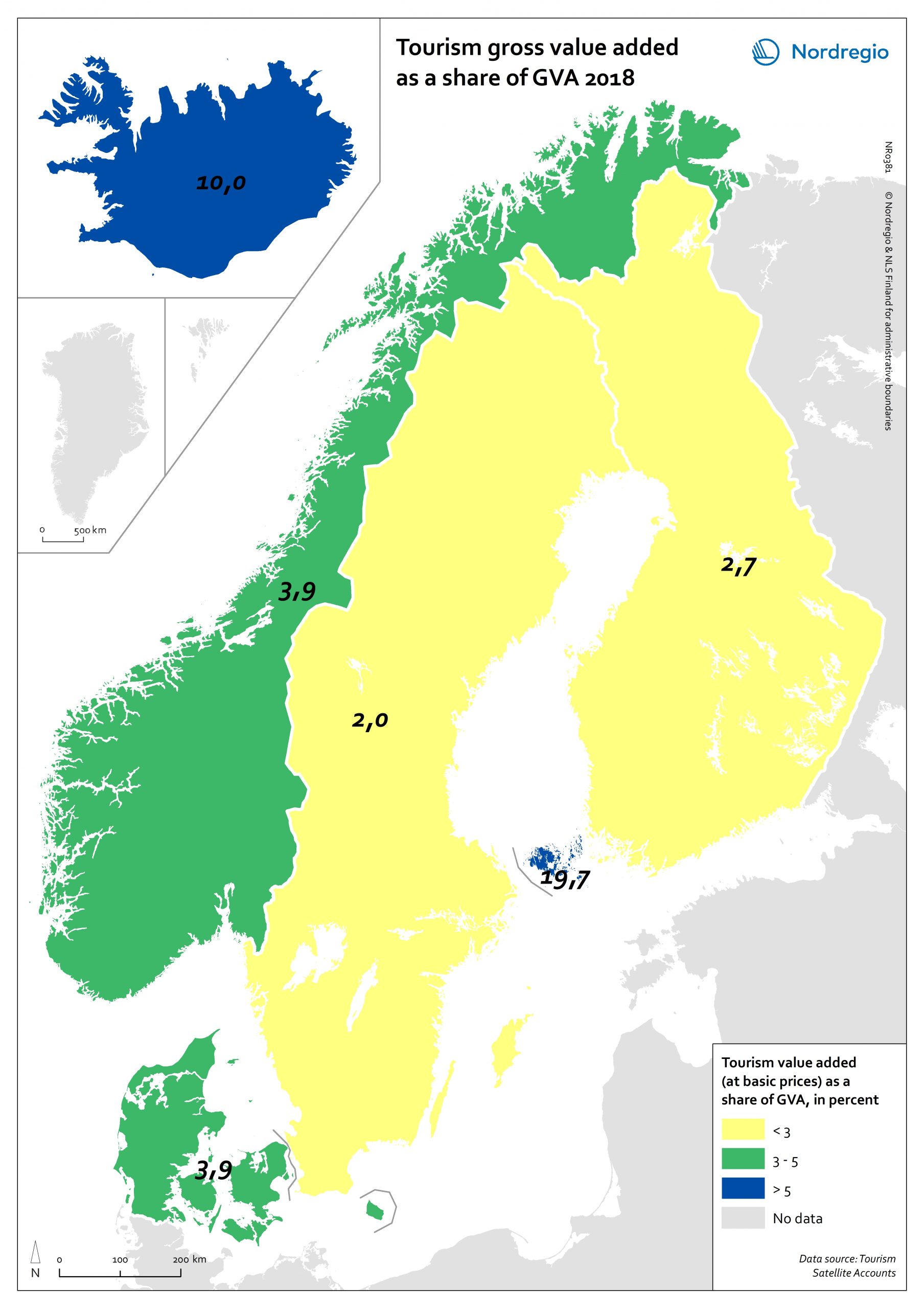

Tourism gross value added as a share of GVA 2018

Tourism gross added value (GVA) corresponds to the part of GVA generated by all industries in contact with visitors. This indicator is measured as a percentage of total GVA at basic prices in 2018 (No data for Greenland and Faroe Islands; data for Finland includes Åland). Data were retrieved from each country’s tourism satellite account. Åland and Iceland stand out as the country or territory where tourism added value accounts for over 10% of the total GVA. For Åland, tourism is so important an industry that added value related to tourism is equivalent to nearly 20% of the total GVA in Åland. The share of tourism related GVA is close to 4% of the total GVA in Norway and Denmark, and lower than 3% in Finland and Sweden.

2021 February

- Economy

- Nordic Region

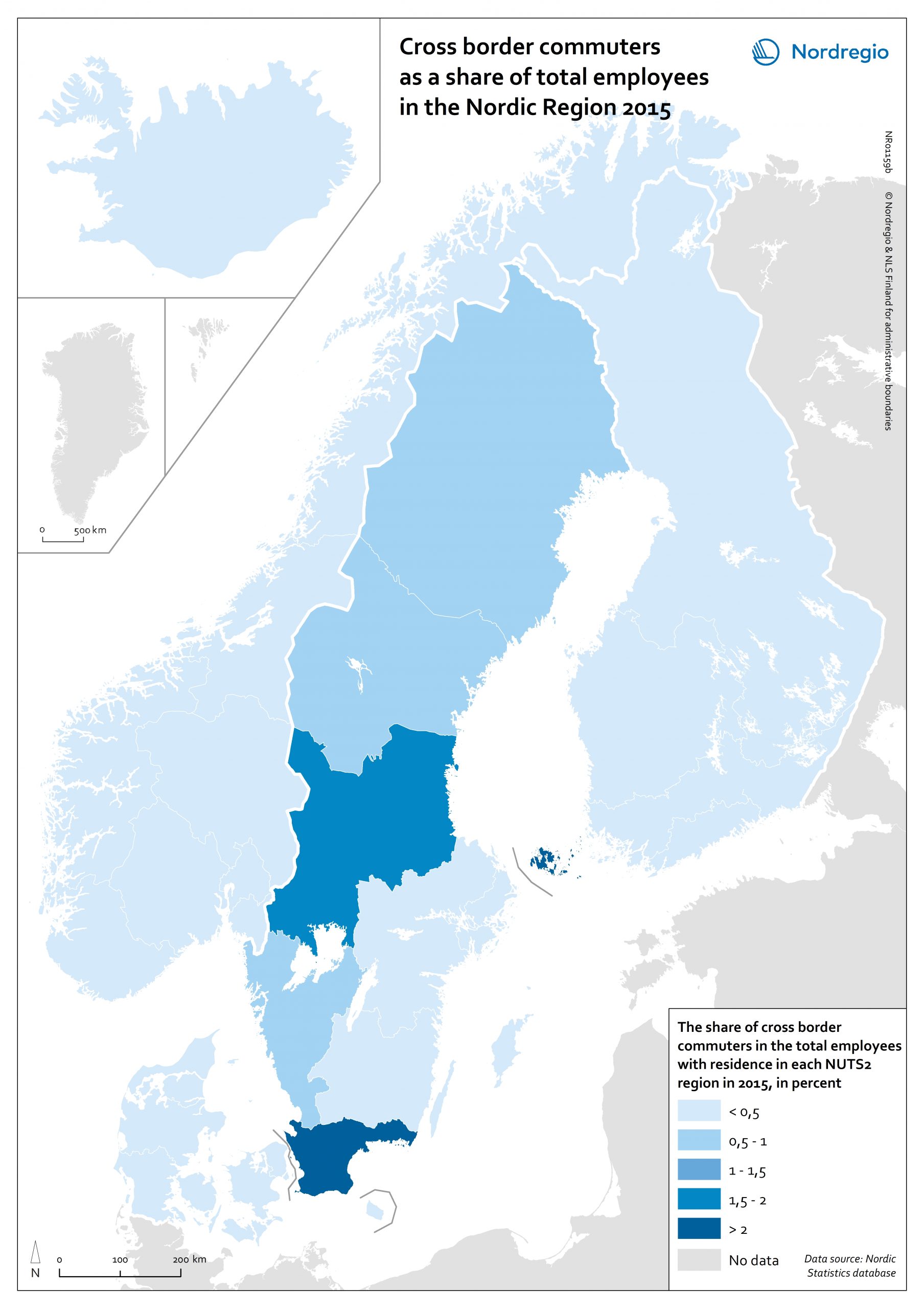

Labour market impacts of COVID-19

On May 17, 2020, 94% of the world’s workers were living in countries with some form of workplace closure measures in place (ILO, 2020). While it is too early to make predictions about the long-term consequences of this, it is possible to make some observations about the short-term labour market impacts in the Nordic Region. The map shows the number of people who registered as unemployed in April 2020 compared with the number of people who registered as unemployed in April 2019 at the municipal level for Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden and Åland Islands and at the national/territory level for Iceland and the Faroe Islands. The shading represents the increase in percent, with darker colours showing higher relative increases compared to the previous year and lighter colours lower relative increases. Municipalities shaded in blue on the map did not experience an increase in unemployment registrations in April 2020 compared to April 2019. Overall, the number of unemployment registrations across the Region was 38.9% higher in April 2020 than in April 2019. This increase equates to a total of 220 354 Nordic workers and has affected almost all Nordic municipalities and regions to some degree. Proportionally speaking, Norway saw the largest increase (69%), followed by Iceland (59%), Denmark (48%), Sweden (41%), and Finland (24%). Though between-municipality variation is evident, the greatest differences appears to be between countries. Interestingly, many Swedish municipalities along the southern coast between Sweden and Norway saw increases more consistent with the overall trend observed in Norway. This may be a reflection of the prevalence of cross-border commuting in these regions. It is important to note that the labour market situation in April 2019 has some baring on the results shown on the map. For example, the appearance of a sharper relative increase in Norway is primarily…

2020 October

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

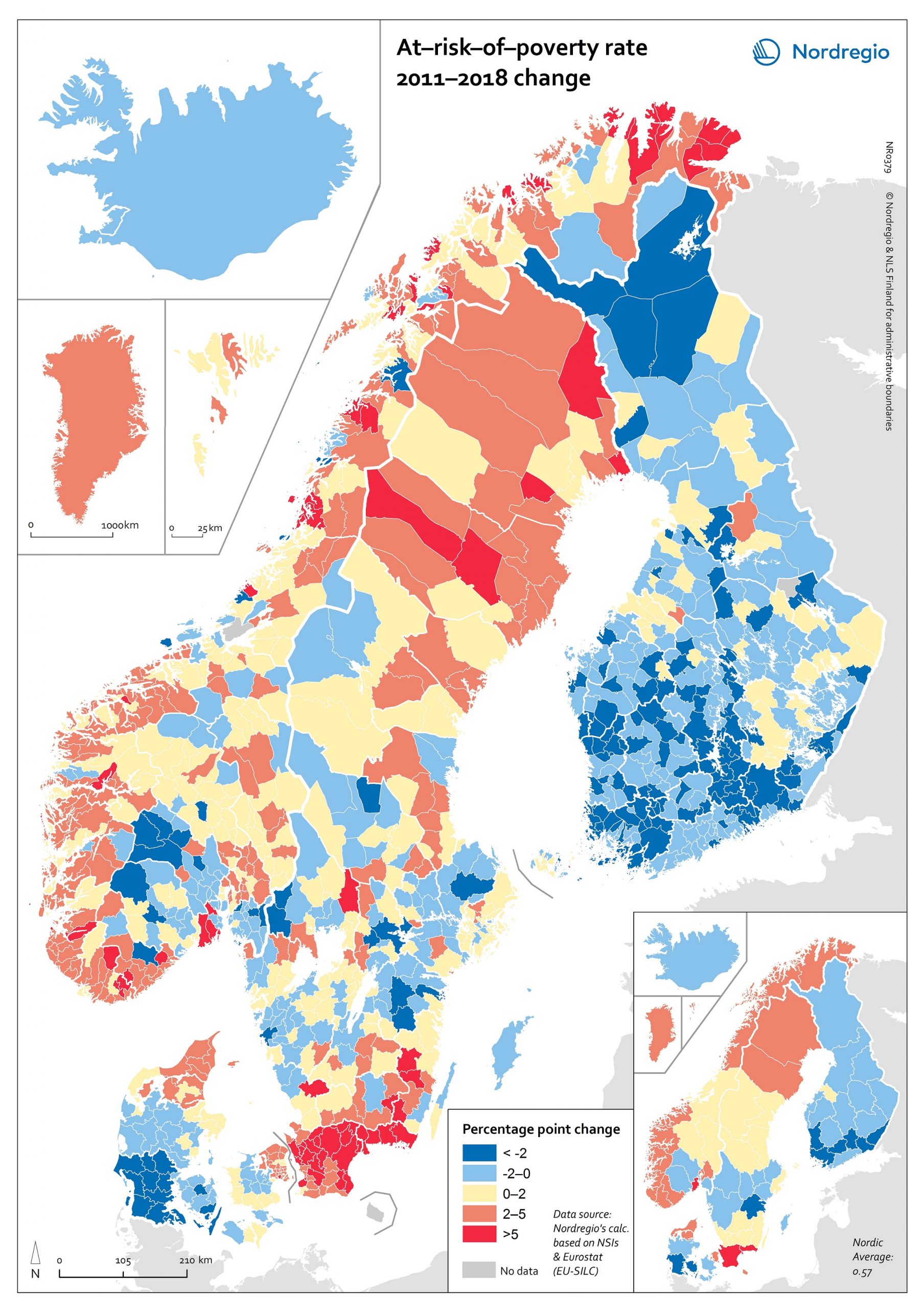

At-risk-of-poverty rate 2011-2018 change

The map shows the “at-risk-of-poverty” (AROP) rate in the Nordic Region. For the period from 2004 to 2018, the AROP rate increased in all Nordic countries except Iceland. This trend was strongest in Sweden. In Finland the AROP rate has been decreasing during the past few years, in line with what has previously been indicated – namely, on account of economic turmoil. This points to one of the weaknesses of using the AROP rate alongside several other measures of inequality. That is, while people have become poorer due to the economic crisis, the at-risk-of-poverty rate has paradoxically gone down. In addition, the AROP rate for Finland is higher in 2018 than it was in 2004. Looking at these trends on a regional level over a period of time (between 2011 and 2018), we can see that the AROP rate has decreased in almost all areas of Finland, whereas the pattern is rath er more varied in the other Nordic countries (we can also see a cohesive area in the south of Denmark where the AROP rate has decreased.) Again, Sweden has the most regions displaying increases in the AROP rate. Finland and Sweden contain the largest differences between the regions with the highest and lowest AROP rate. Hence the greatest regional differences are to be found in Sweden and Finland. Sweden also has the highest average AROP rate. About the At-risk-of-poverty The at-risk-of-poverty rate is a common measure of relative poverty and social inclusion. Most notably, it has been used for monitoring the EU2020 goal of inclusive growth. The at-risk-of-poverty rate is normally defined as “the share of people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfer) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfer.” (Eurostat). The indicator is…

2020 October

- Demography

- Economy

- Nordic Region

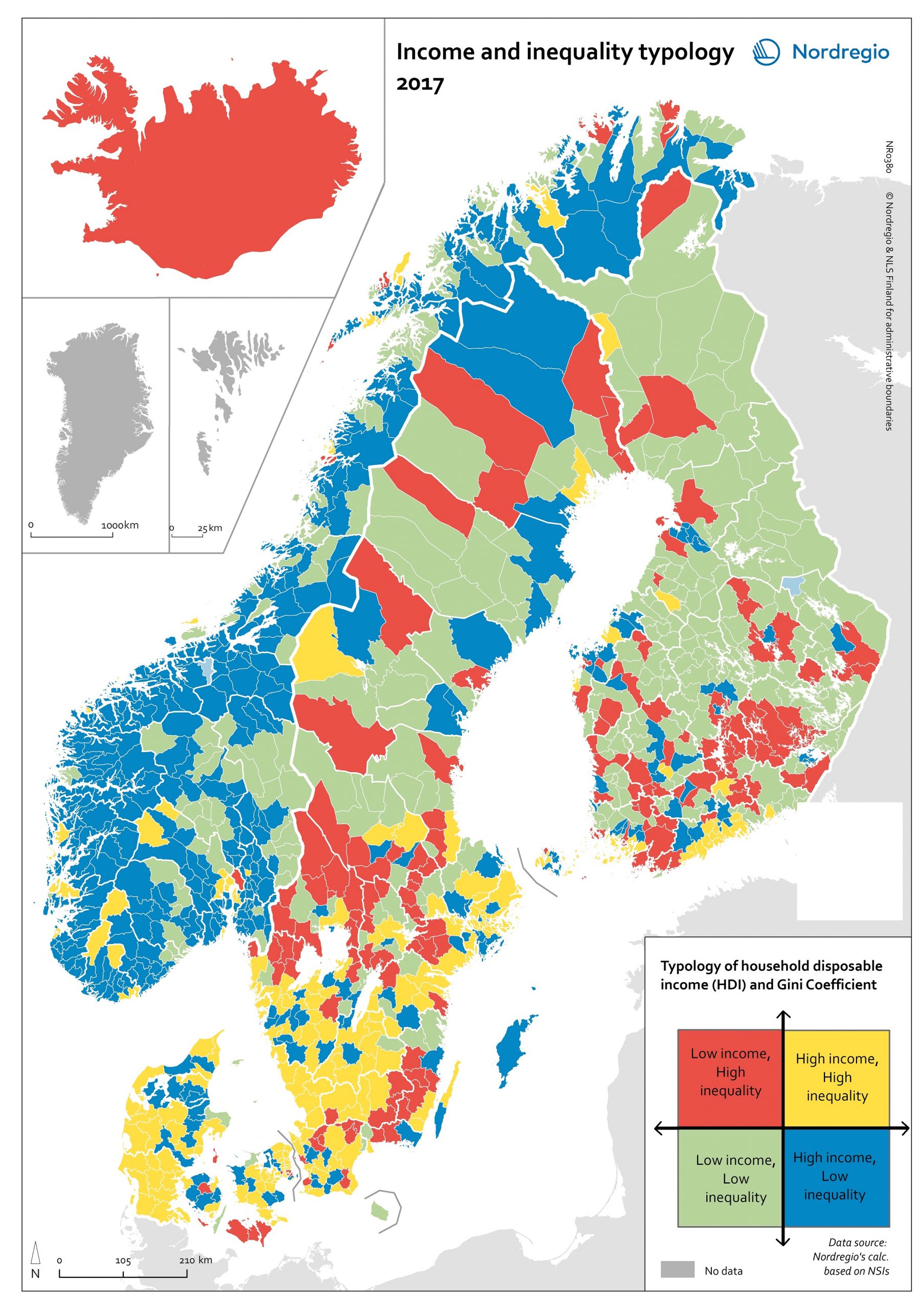

Income and inequality typology 2017

The map shows a typology, combining two indicators to display income disparities between and within municipalities. The map combines measurements of household disposable income (HDI) and the Gini Index to create four “types” of income distribution. Household disposable income is a common measure of income inequality. It measures the capacity of households (or individuals) to provide themselves with consumable goods or services. Comparing average HDIs is a convenient way of understanding inequality between municipalities. The Gini Index measures the extent to which the distribution of household income deviates from an equal distribution level. The Gini Index is therefore useful in understanding the inequality that exists within municipalities. Combining these measurements provides a comprehensive geographic overview of income in equality across the Nordic Region, both within and between municipalities. The municipalities shaded in yellow on the map have an average HDI above the Nordic average, as well as a Gini coefficient above the Nordic average (i.e. high income, but unevenly distributed). This category includes most of the wealthiest municipalities, including municipalities in the capital regions – e.g. most municipalities in the Stockholm Region (Lidingö, Danderyd, Ekerö, Täby, Sollentuna), Copenhagen (Gentofte, Hørsholm, etc.), and Helsinki (Kauniainen). Several municipalities in southern Sweden and Denmark also fall into this category. Most of these have average HDIs just above the Nordic average. The second category (blue on the map) consists of municipalities with HDI above the Nordic average and a Gini coefficient below the Nordic average (i.e. high income and even distribution). Most municipalities in this category are in Norway. Norway has a higher HDI and more even distribution than the other Nordic countries. The third category (green on the map) consists of municipalities with both an HDI and a Gini coefficient below the Nordic average (i.e. lower income, but more evenly distributed). This category…

2020 October

- Economy

- Nordic Region

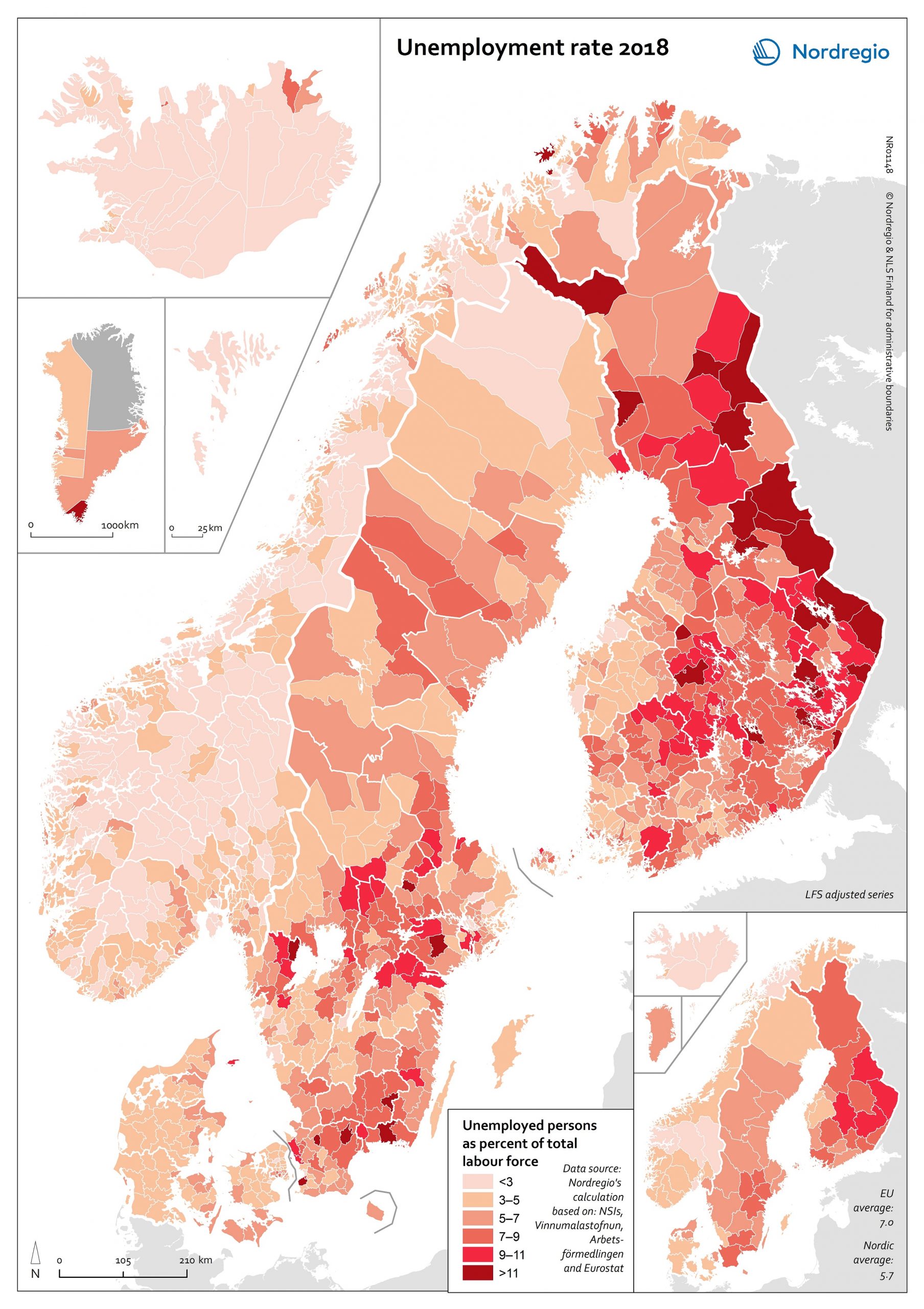

Unemployment rate 2018

The map shows the unemployment rate in the Nordic counties at the municipal level in 2018. Unemployment is measured as the total number of unemployed (i.e. people who were not in employment, but seeking job and available to take up an employment) as share of the total workforce (i.e. employed plus unemployed). The map is based on data from the labour force survey, which is the official way of measuring unemployment. In order to show the municipal level register data has been used as an allocation key. The lighter shades on the map represent lower levels of unemployment, and the darker shades represent higher levels. The Nordic Region has a low average unemployment rate (5.7%) compared with the EU average (7.0%). There is, however, substantial regional variation, both within and between countries. The lowest unemployment rates are found in Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands. The highest rates can be found in Finland (particularly in the east ern municipalities), parts of southern Sweden, and Kujalleq (Greenland). Unemployment rates in Den mark are higher than those found in Iceland and Norway, but lower than those found in Sweden and Finland – with the highest rates found in Nord Jylland. The unemployment rate also varies between population groups. In all Nordic countries, for ex ample, the foreign-born population are more likely to be unemployed than their native-born counter parts, particularly if they were born outside the EU (see Figure 4.5). This trend is most pronounced in Sweden and Finland. It can also be observed throughout the EU, where unemployment for foreign-born persons is more than twice that of the native-born population.

2020 October

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

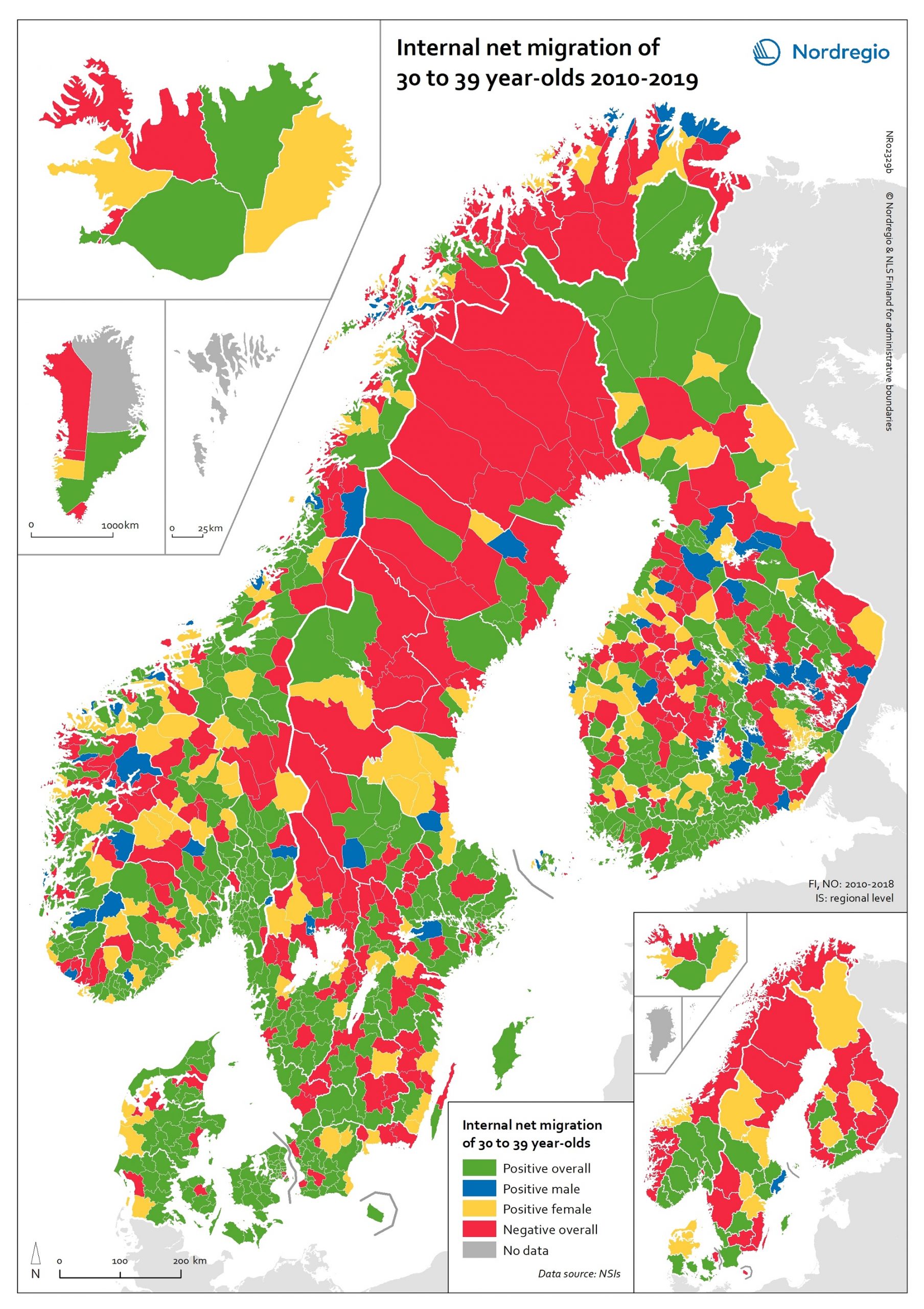

Internal net migration of 30 to 39 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows on 30 to 39-year-olds are of particular interest since it is often assumed that the future of rural regions is dependent upon their capability both to retain their populations and to attract newcomers, returning residents and second home owners. In this context, the map provides a rather positive picture, because a considerable proportion of rural municipalities have experienced positive net migration among females, males, or both sexes across all the Nordic countries. Even so, there is negative net migration among both females and males in many municipalities in northern Sweden, north-eastern Norway and eastern Finland, in addition to several inland municipalities within these countries. Interestingly, there is negative net migration among both sexes across all the capital city municipalities of the Nordic Region. According to the regional map, the capital city regions of Denmark, Iceland and Norway all experienced negative net migration of young people aged 30-39 years between 2010 and 2019. The capital city region of Sweden experienced positive net migration of males and negative net migration of females while the capital city region of Finland experienced positive net migration overall. Despite the majority of peripheral regions experiencing negative net migration of 30 to 39-year-olds during the time period studied, there are also several interesting examples of rural regions which experienced positive female net migration, for example Nordjylland (Denmark), Pohjois-Savo (Finland), Austurland (Iceland), Møre og Romsdal (Norway), and Jämtland (Sweden).

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

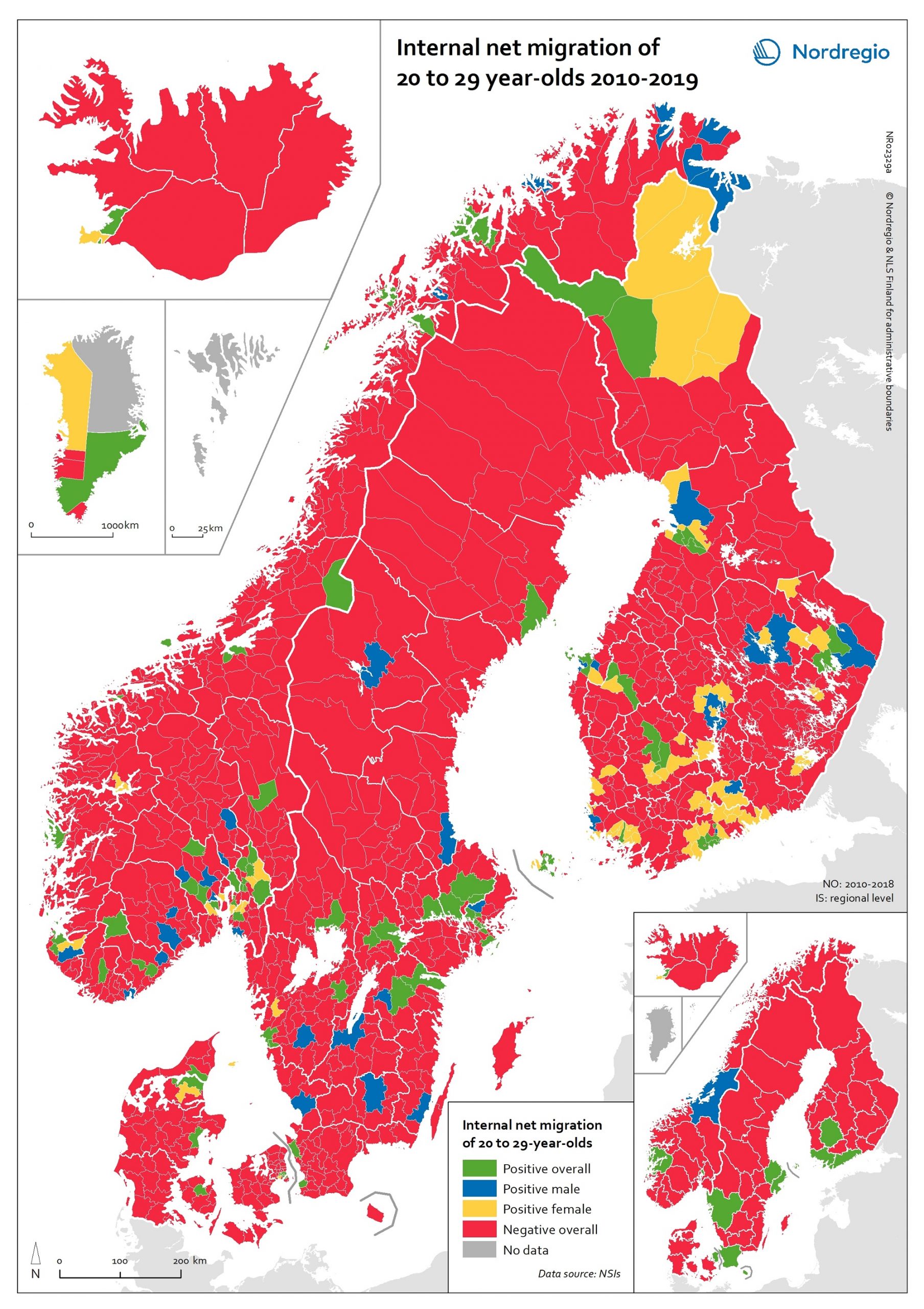

Internal net migration of 20 to 29 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows of 20 to 29-year-olds are of interest since there is a particularly high level of internal migration among young adults across the Nordic countries compared to other EU countries. While the map shows that the great majority of municipalities experience negative net migration of young adults in favour of a few functional urban areas and some larger towns, it is possible to observe a number of exceptions to this general rule. The rural municipalities of Utsira, Moskenes, Valle, Smøla, Ballangen and Lierne in Norway have the highest positive net migration rates both for men and women. There are also positive net migration rates for males and females in the peripheral municipalities of Jomala, Kittilä, Lemland and Finström in Finland and Åland. There is positive male net migration but negative female net migration in Gratangen, Loppa, Gamvik, Drangedal and a few other Norwegian rural municipalities, plus Mariehamn in Åland, while several municipalities in remote areas of Finland have positive female net migration but negative male net migration. Some of these patterns may be related to specialised local labour markets, such as fisheries in Loppa, or recreational tourism in Kittilä. In general, the pattern of net migration among young adults is more diverse in Finland (where 72.0% of all municipalities have negative net migration), compared with 84.6% in Norway, 88.9% in Denmark and 89.0% in Sweden. However, it is important to remember that Danish, Finnish and Norwegian municipalities are smaller in size…

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region