72 News

Population change by component 2010-2019

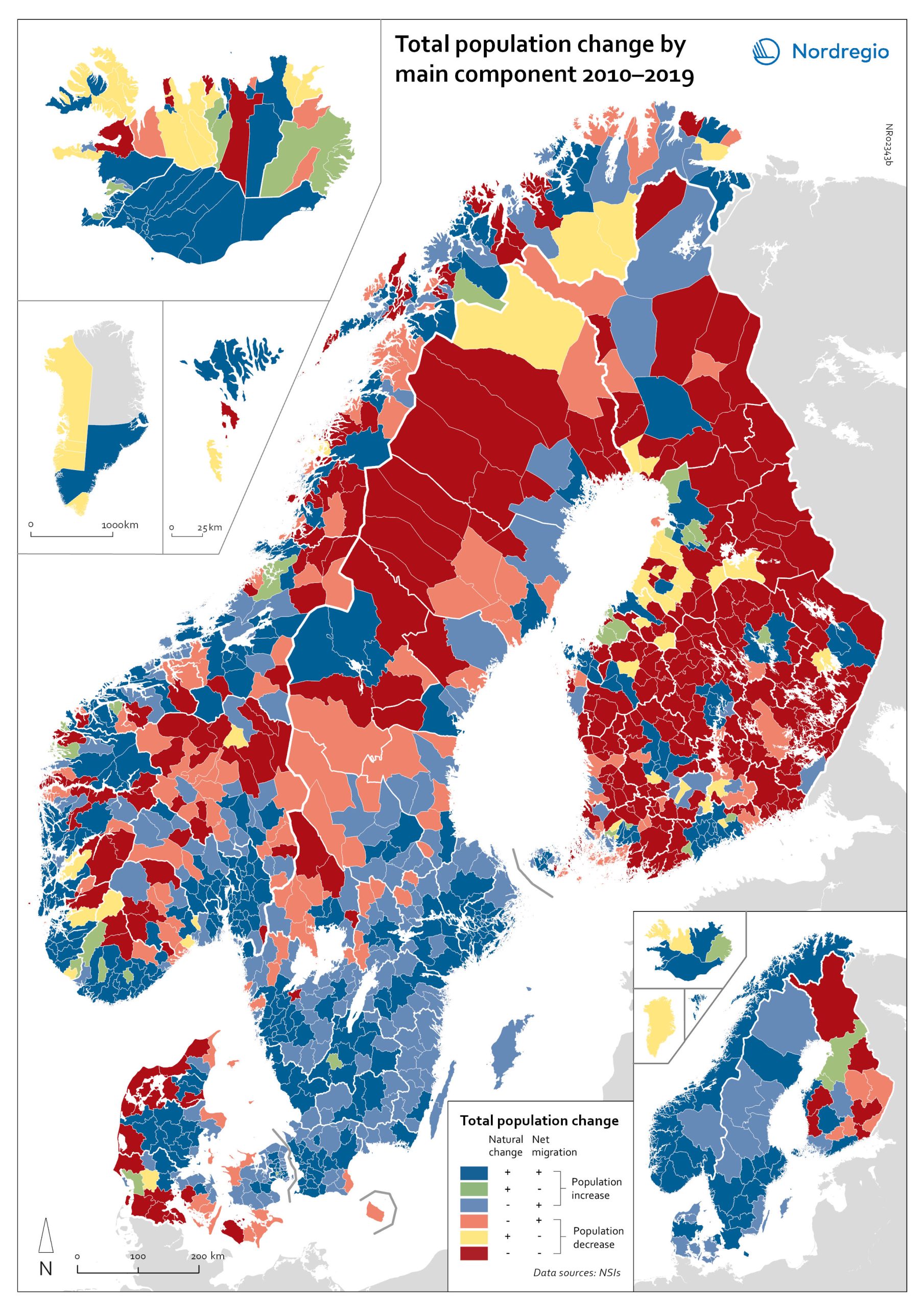

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Net internal migration rate, 2010-2019

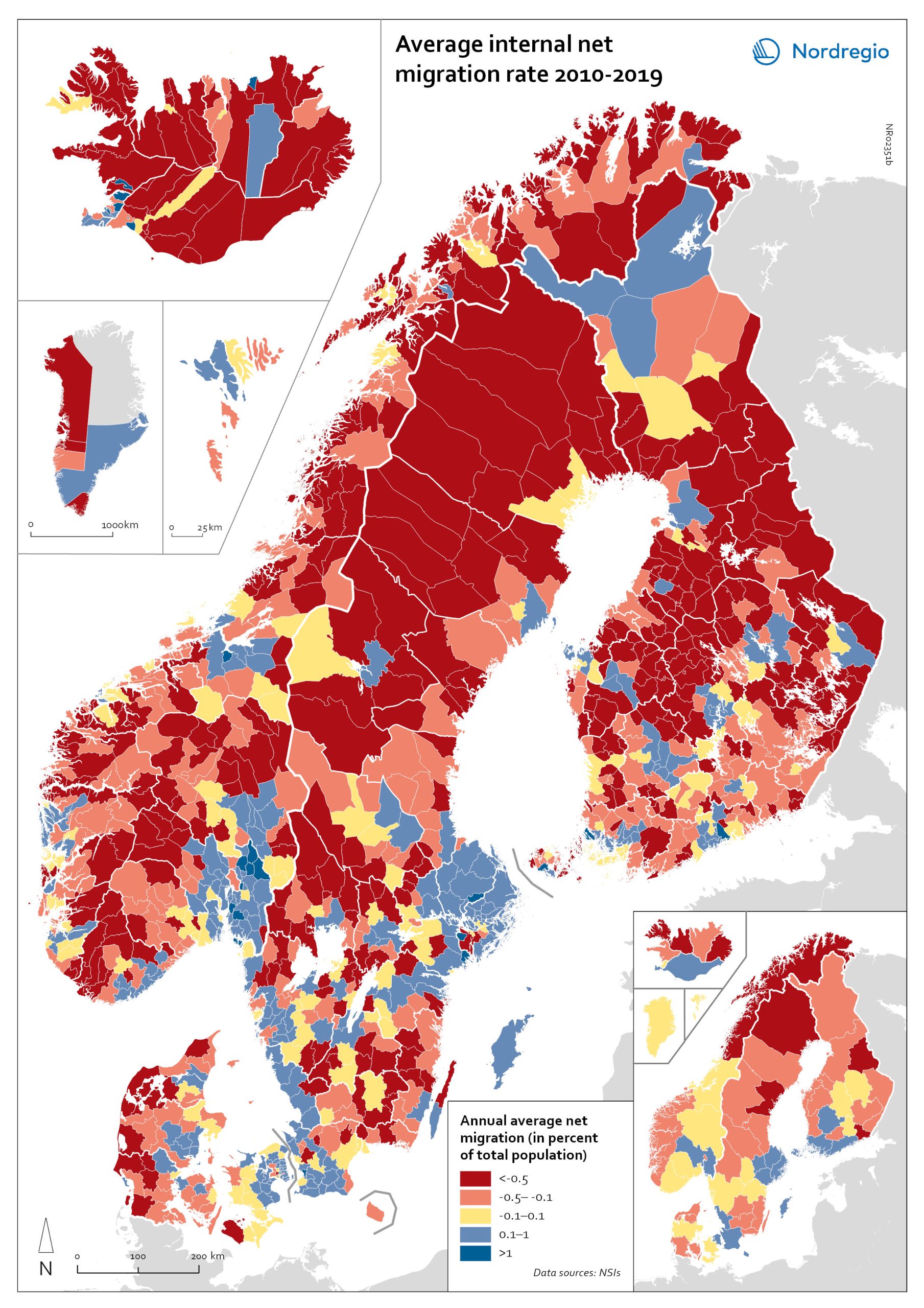

The map shows the annual average internal net migration in 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2020. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Net international migration rate, 2010–2019

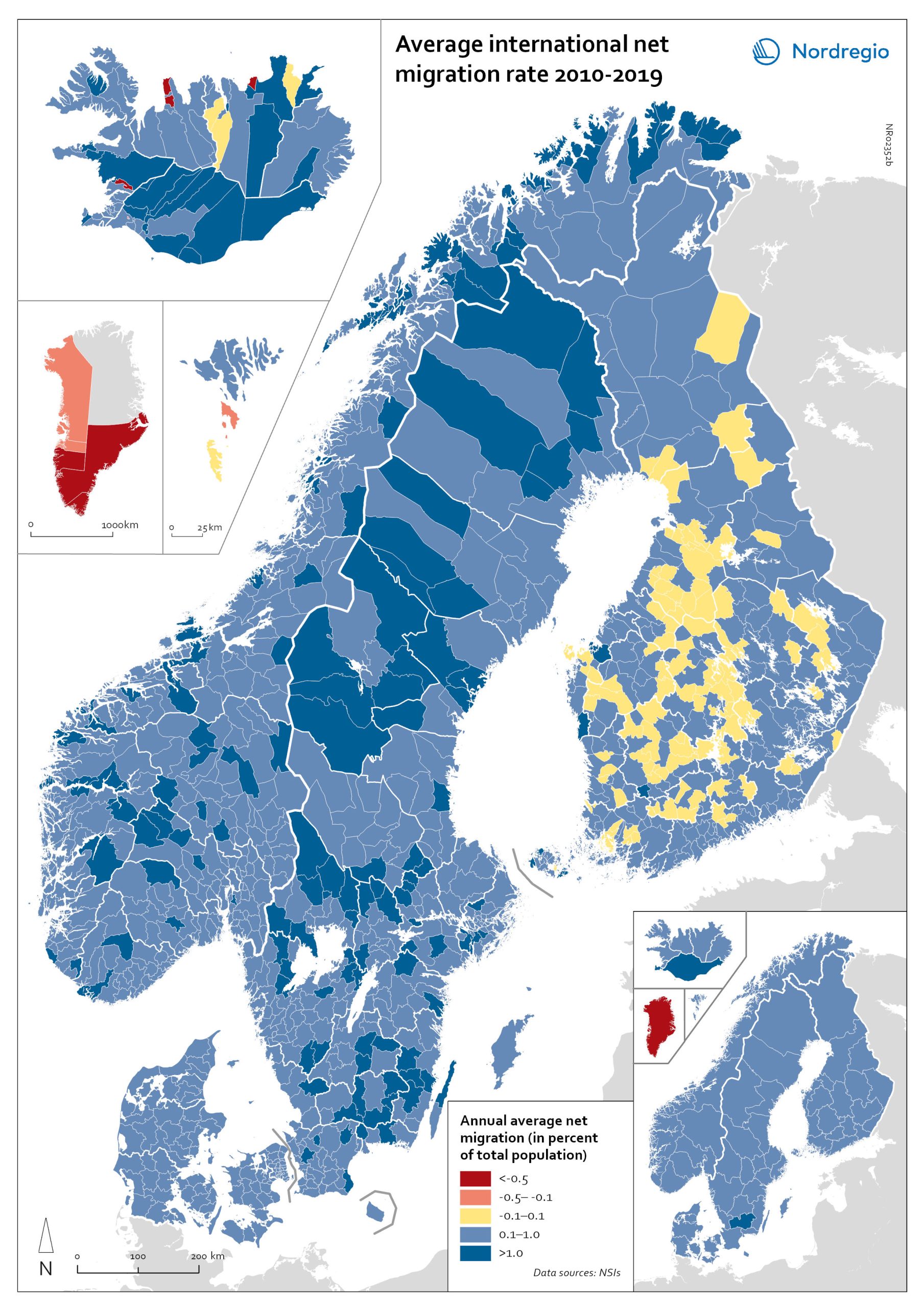

The map shows the annual average international net migration from 2010 to 2019. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2020. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Major immigration flows to the Nordic Region from 2010 to 2019

The map shows annual average immigration flows above 3,000 people, and the growing diversity in their countries of origin Sweden and Denmark, in particular, experienced large inflows from non-Nordic countries during the period 2010-2019, with Sweden standing out as the Nordic country with by far the largest immigrant in-flows. A large portion of these arrivals were from war-torn Syria (an annual average of almost 15,000), followed by Poland (approximately 4,500), United Kingdom, Iraq, India and Iran (around 4,000 each). Denmark experienced a smaller number of inflows above 3,000 people, compared to Sweden. The largest non-Nordic inflows to Denmark were around 5,000 people (per sending country) and included migrants from the U.S., Germany, Romania and Poland. For Norway, large non-Nordic in-flows were limited to Lithuania and Poland. Similarly, Finland had only one major inflow, from Estonia.

2021 December

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

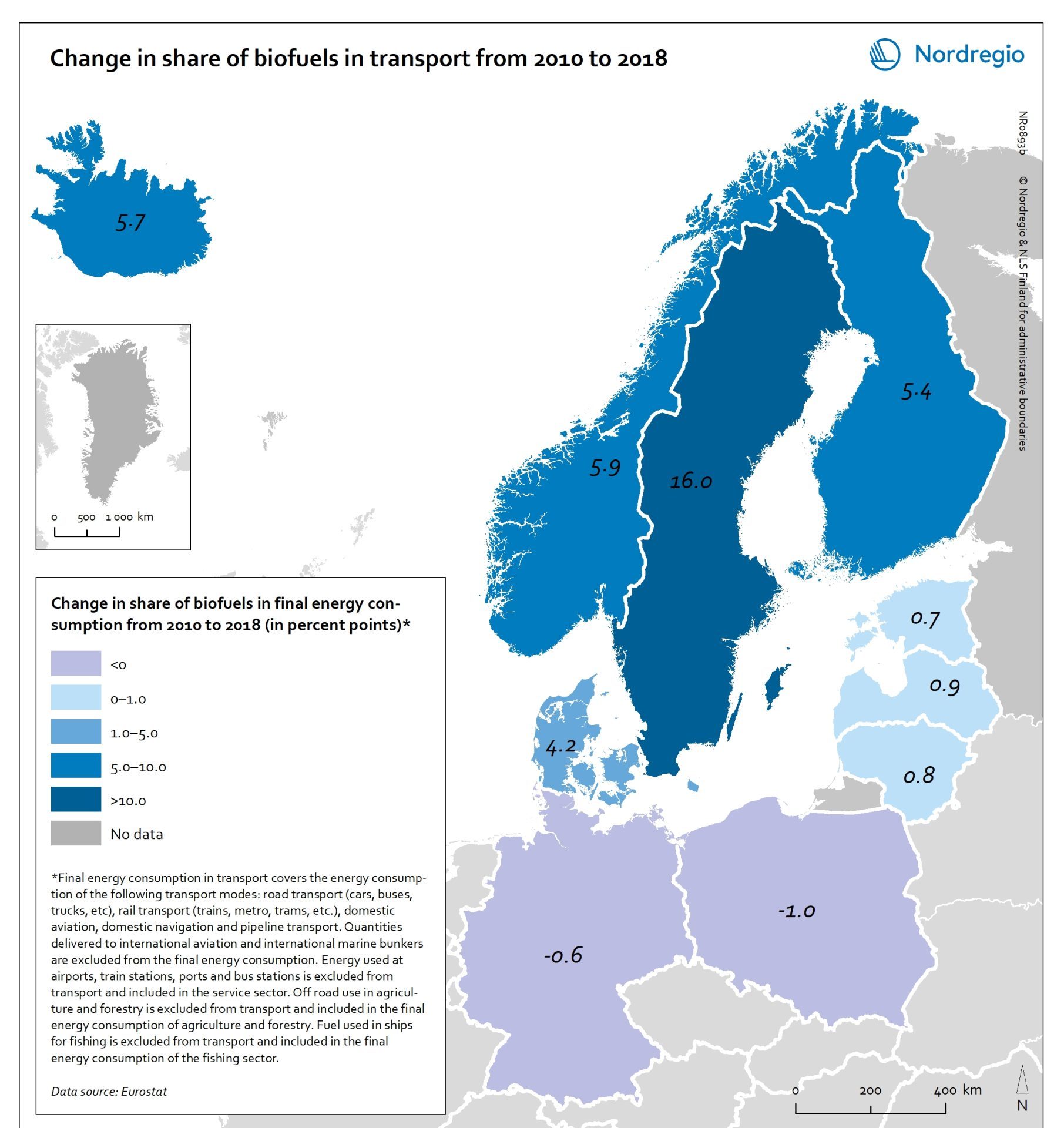

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

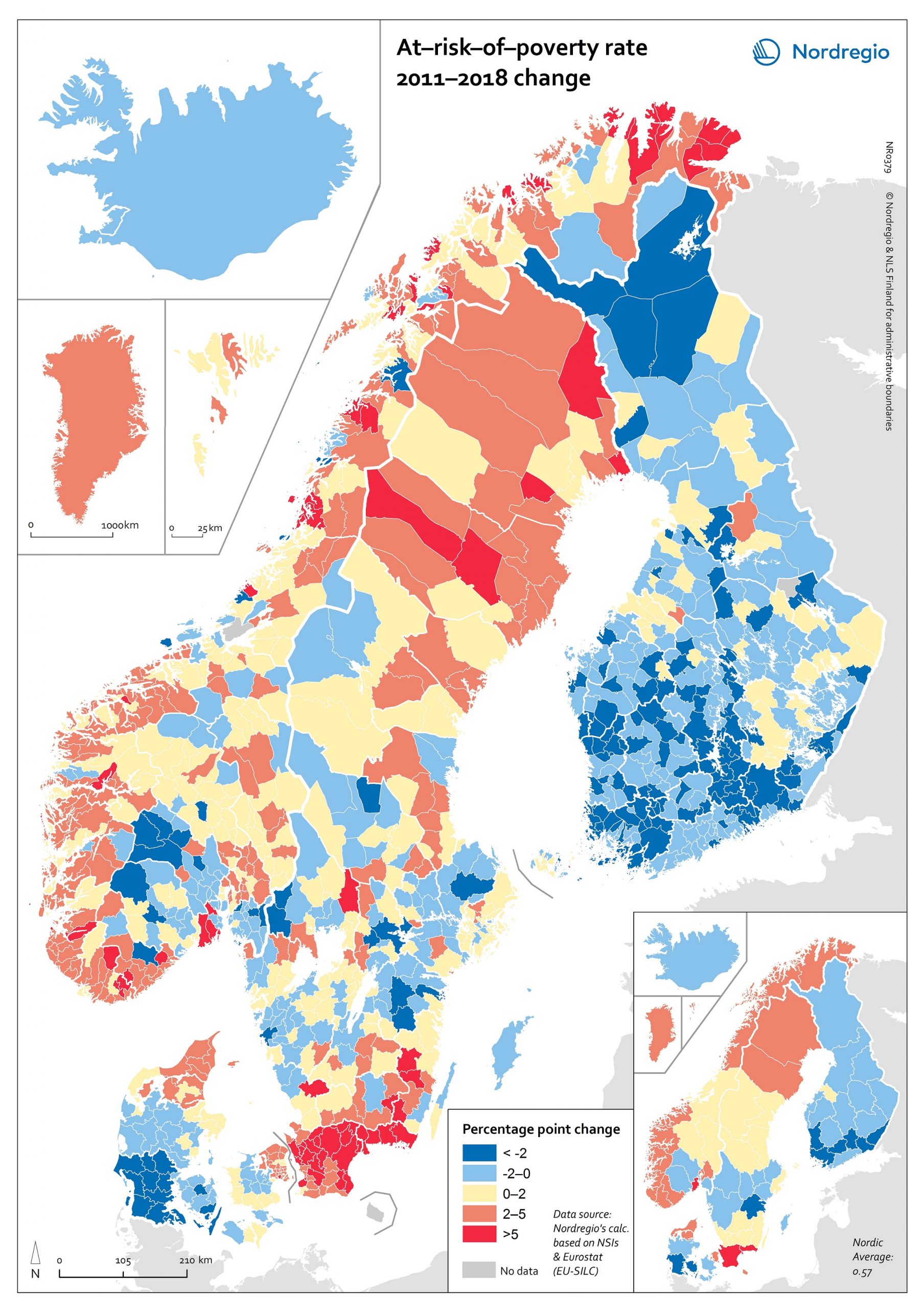

At-risk-of-poverty rate 2011-2018 change

The map shows the “at-risk-of-poverty” (AROP) rate in the Nordic Region. For the period from 2004 to 2018, the AROP rate increased in all Nordic countries except Iceland. This trend was strongest in Sweden. In Finland the AROP rate has been decreasing during the past few years, in line with what has previously been indicated – namely, on account of economic turmoil. This points to one of the weaknesses of using the AROP rate alongside several other measures of inequality. That is, while people have become poorer due to the economic crisis, the at-risk-of-poverty rate has paradoxically gone down. In addition, the AROP rate for Finland is higher in 2018 than it was in 2004. Looking at these trends on a regional level over a period of time (between 2011 and 2018), we can see that the AROP rate has decreased in almost all areas of Finland, whereas the pattern is rath er more varied in the other Nordic countries (we can also see a cohesive area in the south of Denmark where the AROP rate has decreased.) Again, Sweden has the most regions displaying increases in the AROP rate. Finland and Sweden contain the largest differences between the regions with the highest and lowest AROP rate. Hence the greatest regional differences are to be found in Sweden and Finland. Sweden also has the highest average AROP rate. About the At-risk-of-poverty The at-risk-of-poverty rate is a common measure of relative poverty and social inclusion. Most notably, it has been used for monitoring the EU2020 goal of inclusive growth. The at-risk-of-poverty rate is normally defined as “the share of people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfer) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfer.” (Eurostat). The indicator is…

2020 October

- Demography

- Economy

- Nordic Region

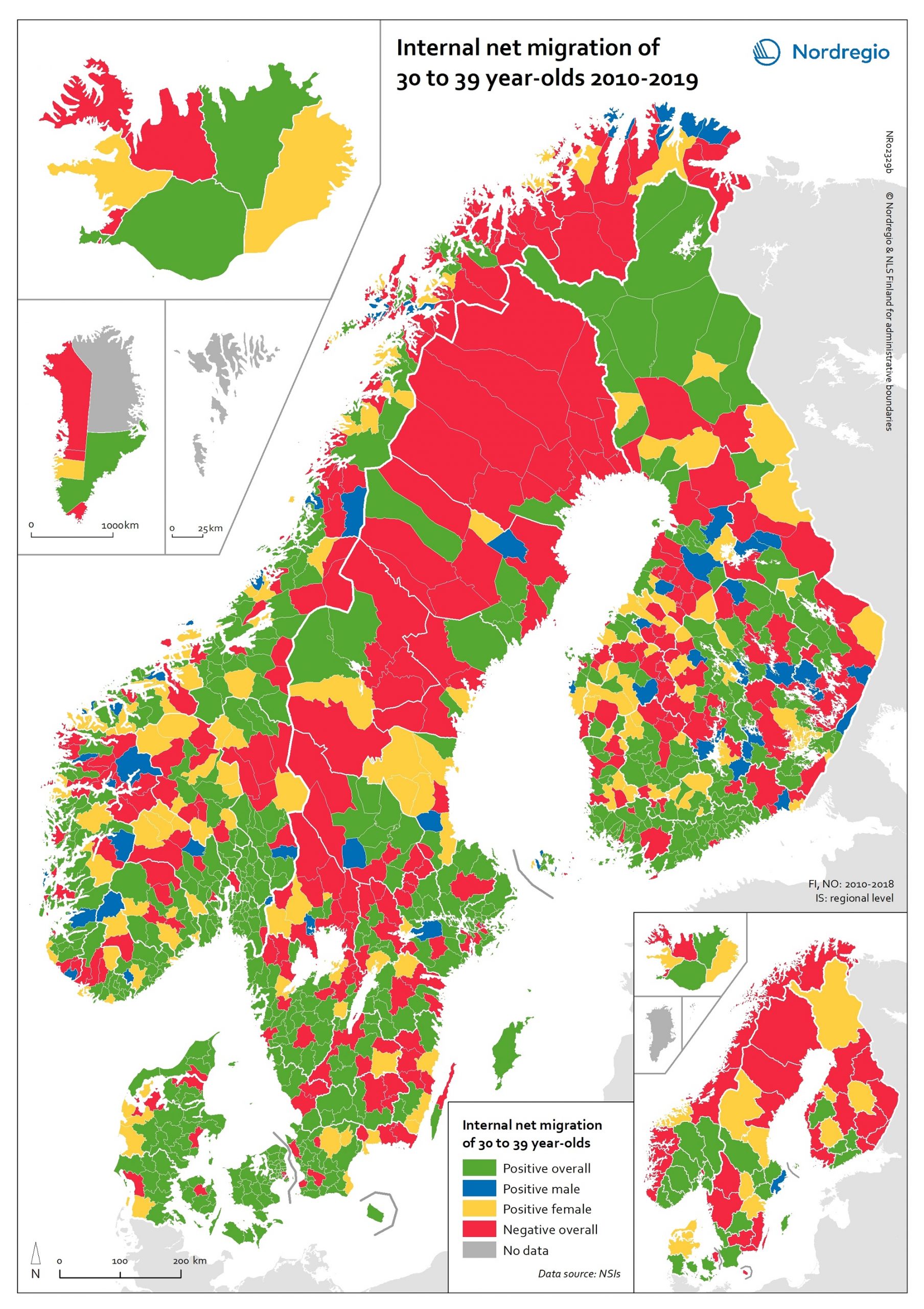

Internal net migration of 30 to 39 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows on 30 to 39-year-olds are of particular interest since it is often assumed that the future of rural regions is dependent upon their capability both to retain their populations and to attract newcomers, returning residents and second home owners. In this context, the map provides a rather positive picture, because a considerable proportion of rural municipalities have experienced positive net migration among females, males, or both sexes across all the Nordic countries. Even so, there is negative net migration among both females and males in many municipalities in northern Sweden, north-eastern Norway and eastern Finland, in addition to several inland municipalities within these countries. Interestingly, there is negative net migration among both sexes across all the capital city municipalities of the Nordic Region. According to the regional map, the capital city regions of Denmark, Iceland and Norway all experienced negative net migration of young people aged 30-39 years between 2010 and 2019. The capital city region of Sweden experienced positive net migration of males and negative net migration of females while the capital city region of Finland experienced positive net migration overall. Despite the majority of peripheral regions experiencing negative net migration of 30 to 39-year-olds during the time period studied, there are also several interesting examples of rural regions which experienced positive female net migration, for example Nordjylland (Denmark), Pohjois-Savo (Finland), Austurland (Iceland), Møre og Romsdal (Norway), and Jämtland (Sweden).

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

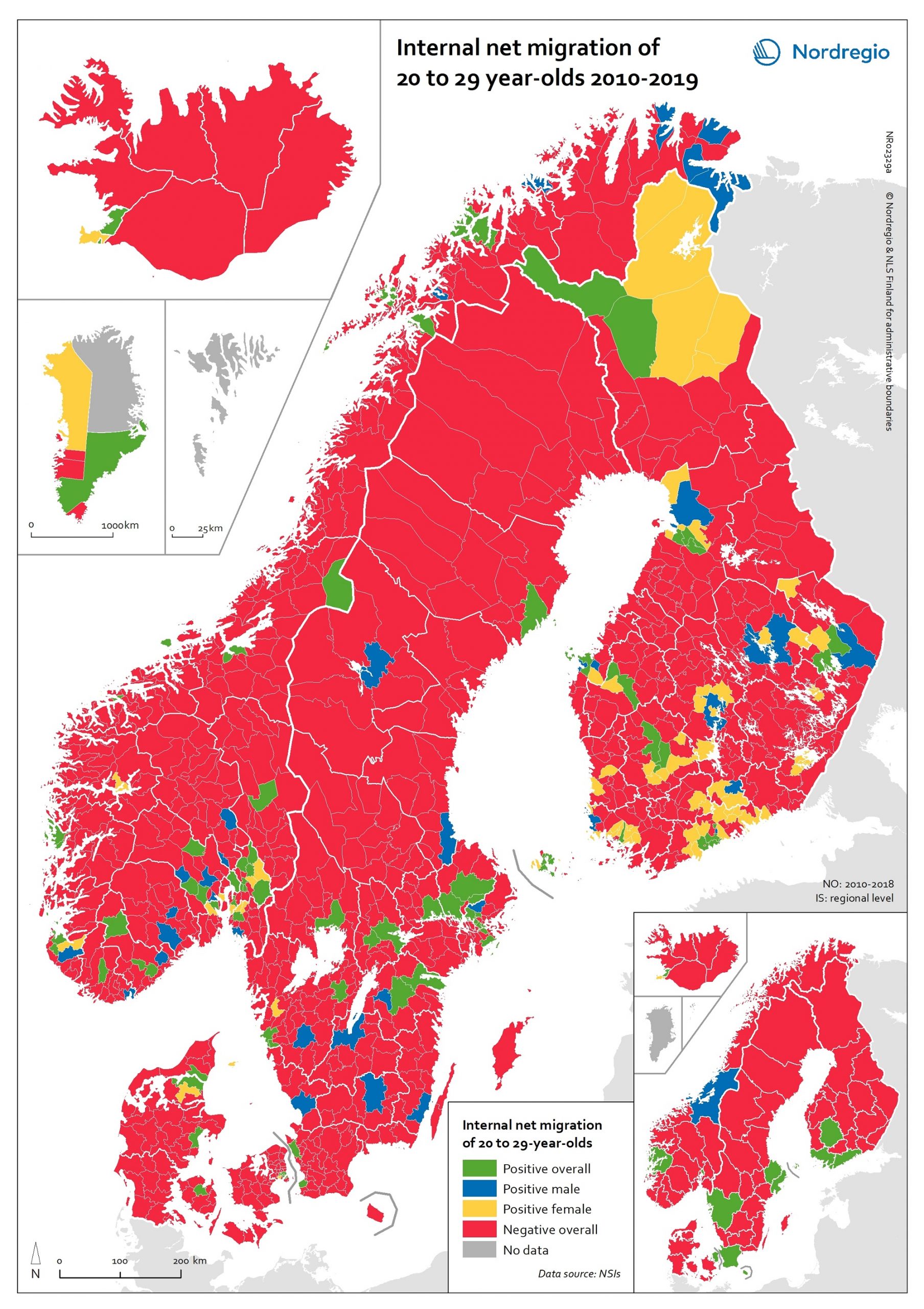

Internal net migration of 20 to 29 years-of-age, by gender, in 2010-2019

This map shows a typology that divides the Nordic municipalities and regions into four migration categories: positive net migration for both males and females (green on the map), positive male net migration (blue on the map), positive female net migration (yellow on the map), and negative net migration for both males and females (red on the map). These migration flows of 20 to 29-year-olds are of interest since there is a particularly high level of internal migration among young adults across the Nordic countries compared to other EU countries. While the map shows that the great majority of municipalities experience negative net migration of young adults in favour of a few functional urban areas and some larger towns, it is possible to observe a number of exceptions to this general rule. The rural municipalities of Utsira, Moskenes, Valle, Smøla, Ballangen and Lierne in Norway have the highest positive net migration rates both for men and women. There are also positive net migration rates for males and females in the peripheral municipalities of Jomala, Kittilä, Lemland and Finström in Finland and Åland. There is positive male net migration but negative female net migration in Gratangen, Loppa, Gamvik, Drangedal and a few other Norwegian rural municipalities, plus Mariehamn in Åland, while several municipalities in remote areas of Finland have positive female net migration but negative male net migration. Some of these patterns may be related to specialised local labour markets, such as fisheries in Loppa, or recreational tourism in Kittilä. In general, the pattern of net migration among young adults is more diverse in Finland (where 72.0% of all municipalities have negative net migration), compared with 84.6% in Norway, 88.9% in Denmark and 89.0% in Sweden. However, it is important to remember that Danish, Finnish and Norwegian municipalities are smaller in size…

2020 October

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Internal net migration as percentage of population 2010–2018

This map shows annual average internal net migration rate at the municipal and regional level in 2010-2018. The map shows the percentage change from internal migration for the period 2010 to 2018. Internal or domestic migration refers to migration between municipalities and regions within the same country. The blue areas on the map show municipalities/regions with positive internal net migration (i.e. more people arriving than departing), the red areas show municipalities/regions with negative internal net migration (i.e. more people departing than arriving) and the yellow areas show municipalities/regions with balanced internal net migration rates (i.e. comparable numbers of people arriving and departing). The trend revealed is that internal migration movements are directed towards larger city regions, with many rural periphery regions losing people. The loss of people in some of these regions is felt especially acutely because of the age selectivity of migration, with young people leaving in large numbers, accelerating the ageing of the population structure in regions with high out-migration. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Change in household disposable income 2011–2017

This map shows the change in household disposable income at the municipal level during the period 2011-2017. The blue colours indicate an increase in average household disposable income and the red colours indicate a decrease in average household disposable income. Household disposable income is defined as the sum of the income of a household (i.e. income from employment, net property income, social transfers and social benefits) minus direct taxes and social contributions, with dividends and net interest taken into consideration. The map reveals that a striking difference between the trends in Finland and Åland and those in the rest of the Nordic Region. The average household disposable income has fallen in almost half of the municipalities in Finland and Åland, but increased in all municipalities in Denmark, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Vimpeli, Rautjärvi and Pukkila, all in Finland, are the municipalities which experienced the largest drop in average household income between 2011 and 2017. This negative trend in municipalities in Finland was largely the consequence of a prolonged recession in the early 2010s, when the manufacturing sector was hit by a structural crisis. The situation was exacerbated by out-migration to urban areas and a rise in the unemployment rate in Finland, which peaked in 2015. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Migration

- Nordic Region

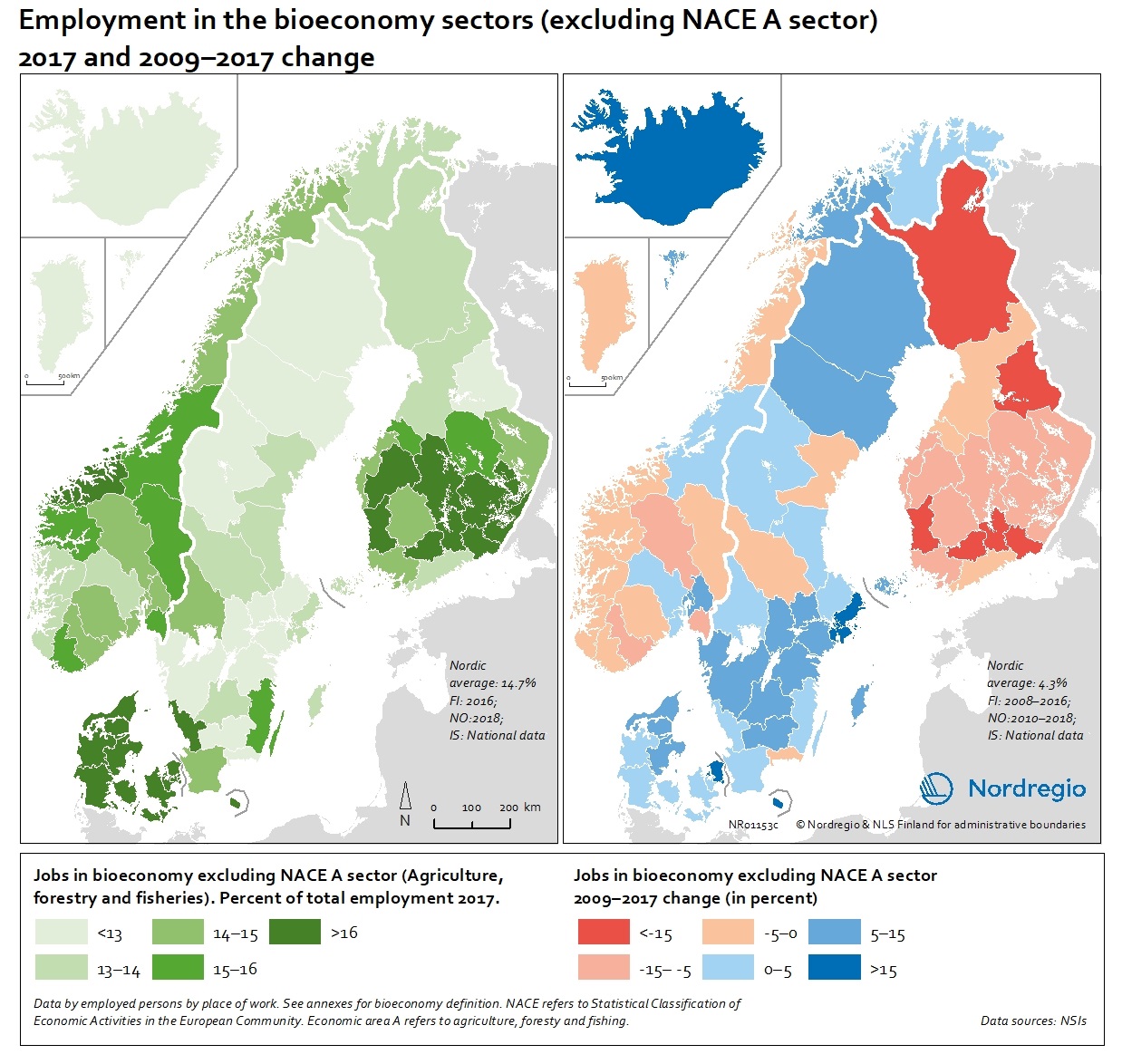

People employed in the bioeconomy excluding NACE sector A in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These maps show the number of jobs in the bioeconomy sectors as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right), excluding the NACE A sectors. The non-NACE-A sectors have seen a more moderate decrease in Finland but a noticeable increase in most parts of Sweden, Denmark and the Faroe Islands and a remarkable increase in Iceland with more than 15% (Figure 9.3). The average increase in the Nordic Region is 4.3% in the non-NACE-A sectors. There are also notable differences within the countries, showing that regional differences matter. In Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, there is a positive trend in most regions, but in Finland, almost all regions are losing jobs in the primary industries. In Norway and Sweden, some regions show positive development while others are in decline. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Internal and international net migration 2010-2018

This map shows internal and international net migration in 2010-2018. The map shows the combination of domestic migration (left-hand bar) and international migration (right-hand bar), with red indicating net out-migration and green indicating net in-migration, for the 66 regions within the Nordic Region in the period 2010 to 2018. The size of the bar indicates the size of the net flows. All regions have had positive international migration since 2010, which is not surprising given the size of the international migration flows into the Nordic Region in recent years. Overall in the Nordic Region, there were either domestic migration losses and international migration gains or gains from people moving both from elsewhere in the country and from abroad. The gains from international migration far exceeded those of internal migration in almost all regions that experienced net gains from both streams. Due to these different patterns of internal and international migration, nearly all regions are becoming much more diverse in terms of the size of foreign-born populations. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Change in Gini coefficient 2011-2017

This map shows the change in disposable income Gini index at the municipal level during the period 2011-2017. The blue shades indicating a decrease in income inequality and the red shades indicating an increase in income inequality. The figure reveals that the situation is very different across the municipalities and countries of the Nordic Region. Income inequality increased between 2011 and 2017 in the vast majority of municipalities across the Nordic Region. The greatest increases are found in rural areas in both Norway and Sweden. These increases are largely explained by an increase in income for households that already had a high income in 2011. However, income inequality decreased in almost a quarter of the municipalities in the Nordic Region during the same period. These municipalities are mainly located in Finland and Åland. The narrowing of the household income gap in many municipalities across Finland is mainly due to the prolonged economic recession in the early 2010s combined with demographic changes (e.g. out-migration and ageing). Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Migration

- Nordic Region

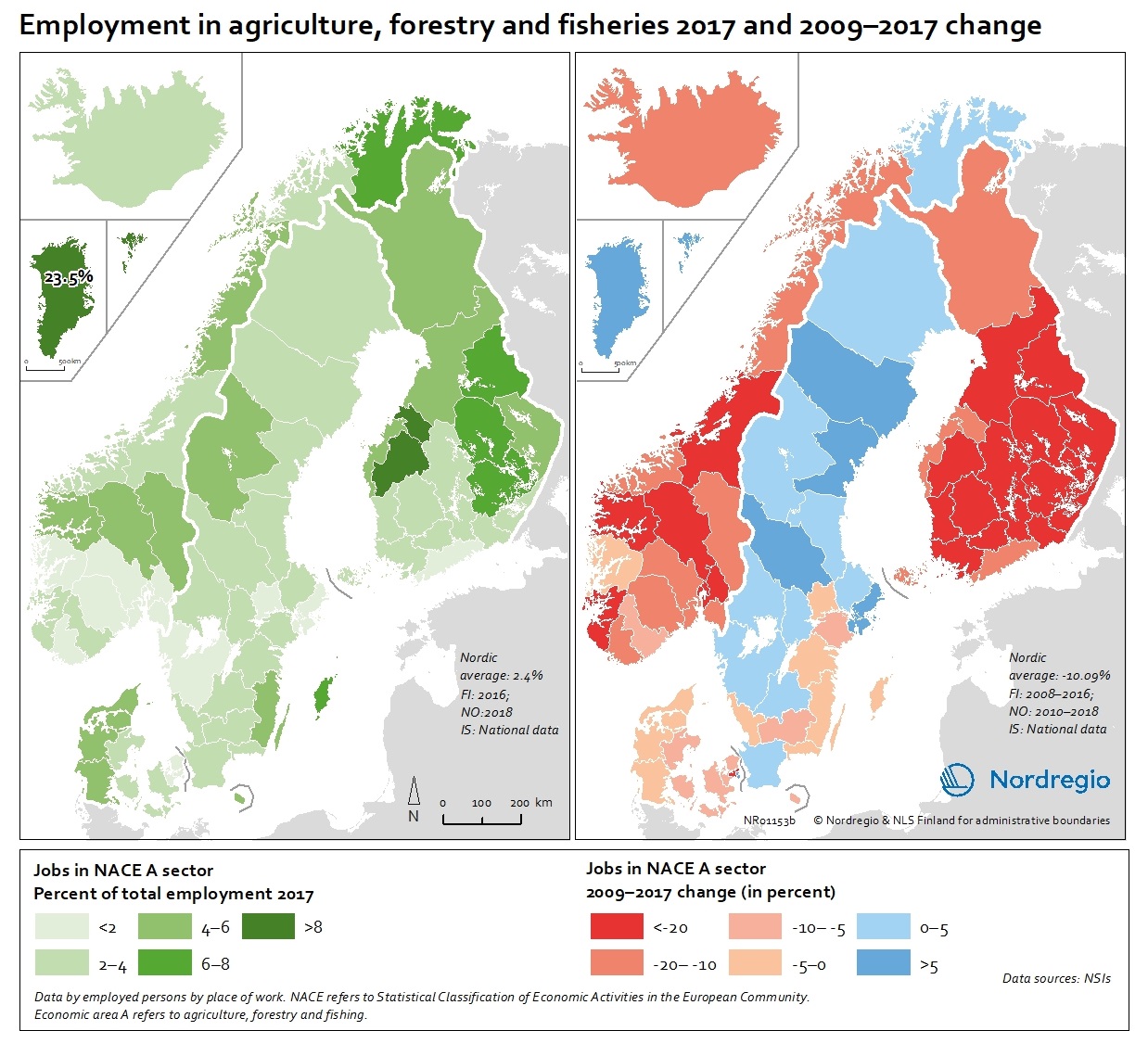

People employed in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors (NACE Sector A) in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These map show the number of jobs in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors (NACE A sectors) as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right). The map (left) indicates ranges of people employed in agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors between below 2% to above 8%, with the highest proportion being in Greenland with 23.5% in 2017. In the EU-28, the overall proportion of the total workforce with jobs in the NACE-A sectors is an average of 4.6%. Overall, the NACE-A sectors show a sharp decline in employment (right map), particularly in Finland, Iceland and Norway (except northern Norway), where the decline was up to 20% between 2009 and 2017. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Total population change by main component 2010-2018

This map shows total population change by main component at the municipal and regional level in 2010-2018. The two components of population change are natural change and net migration. As the map shows, all regions in Denmark, Norway and Sweden experienced population increase due to either a combination of natural increase and net migration or through net migration alone between 2010-2018. In Iceland, all regions experienced both positive natural increase and positive net migration, except for Vestfirðir and Norðurland vestra, which experienced population decline despite experiencing more births than deaths over the period. The regional picture in Finland was more varied, with population decline most pronounced in the east and the north. At the municipal level, the highest overall population growth can be found mostly in the capital regions and bigger cities (e.g. Tampere and Turku in Finland), Central Jutland (Denmark), coastal areas of Norway, southern Iceland, southern Sweden, the northern municipalities of the Faroe Islands and Sermersooq Municipality (Greenland), which contains the capital of Nuuk. The highest overall population decline can be found mostly in the western and southern parts of Denmark, the majority of Finnish municipalities and most inland municipalities in northern Sweden. While the map shows a snapshot of population change for one decade, these trends of population increase in urban regions and municipalities and decline and ageing in periphery regions and municipalities have been underway for some time and are expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

People employed in the bioeconomy including NACE sector A in 2017 and 2009-2017 change

These maps show the number of jobs in the bioeconomy sectors as a share of the total employment in 2017 (left) and 2009-2017 change (right). The share of jobs in the bioeconomy varies from below 15% to above 22.5%. For instance, in the western regions of Denmark, the central and southern regions in Finland, Greenland and some mid and northern regions of Norway, over 22.5% of the working population is employed in the bioeconomy. At the same time, most regions in mid-Norway, in all Finnish and some Danish regions witnessed negative development in jobs in the bioeconomy. In Greenland, Iceland, Faroe Islands, Sweden, Northern Norway and other parts of Denmark the situation is very different and the number of jobs in the bioeconomy has increased. These proportions should also be seen in relation to the increase in total number of jobs17 in most regions in the Nordic countries except for the Finnish regions and Åland where there is a decline in most regions. Read the digital publication here.

2020 February

- Economy

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Population change in Arctic settlements

The map provides an overview of the population change in Arctic settlements with 500 inhabitants or more during the period 2000 to 2017. The purple underlaying layer shows the extent of permafrost across the Arctic. The circles indicate settlements with 500 inhabitants or more and are proportional to the total population in 2017. Blue tones indicate population growth between 2000 and 2017, while red tones indicate population decline. Four zoomed-in maps show areas with high settlement density – Arctic Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Alaska. In Alaska, population increased in the largest settlements between 2000 and 2017. The population decline in small settlements located far from the two large cities – Anchorage and Fairbanks – has been caused by outmigration, which has cancelled out the positive natural population growth. In the Canadian Arctic, most people live in a few settlements. Similar to Alaska, the population increased in the largest settlements and decreased in small settlements. Most of the smaller settlements in Arctic Fennoscandia have witnessed a population decline between 2000 and 2017, except in Norway. The dominant pattern in Fennoscandia is a population growth in larger settlements and a population decline in surrounding smaller settlements. This is similar to the pattern observed in the other Nordic Arctic countries – Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands. New inhabitants settled in the capitals (Reykjavik, Nuuk, and Torshavn) and regional centres, from both domestic and international locations, while settlements in sparsely populated areas are becoming less attractive to incomers. In the Russian Arctic, the regions can be divided into the oil and gas areas of the Khanty-Mansi and Yamal-Nenets, and other areas. The population is growing in the oil and gas areas and declining slowly in the others. Over 75% of the settlements have been shrinking throughout the 21st century, mainly because…

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

- Migration

Infant mortality rate in the Arctic

The map shows the infant mortality rate in the Arctic regions in 2012-2016. The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths per 1 000 live births of children under the age of one year. Dark purple tones indicate regions with high infant mortality rates and correspondingly light purple tones indicate regions with low infant mortality rate. In Chukotka (Russian Federation) and Nunavut (Canada) the infant mortality was notably higher than the overall Arctic average: about 20 infant deaths per 1 000 live births. Regions with lowest infant mortality rate were Troms (Norway, 1,8), Iceland (2,0), Lapland (Finland, 2,0), Norrbotten (Sweden, 2,5), and the Yukon (Canada, 2,9).

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography

Life expectancy in the Arctic

The map shows the life expectancy at birth in the Arctic regions in 2012-2016. Dark brown tones indicate regions with high life expectancy and correspondingly light brown tones indicate regions with short life expectancy. As one of the UN Sustainable Development indicators for good health and well-being, life expectancy at birth measures the general health status of a population. Life expectancy at the national level is highly correlated to national income indicators such as GDP per capita. In the Arctic region, the life expectancy in 2012-2016 was 74,7 years. Regional differences are partly due to specific lifestyles, but also to the local environment, as well as the politics and institutions that influence the local economy, access to local services and care, general educational levels. In Iceland (82.5 years), Quebec (82,2 years) (Canada), Faroe Islands (82,1 years), as well as in Troms and Nordland (Norway), Norrbotten (Sweden), and Lapland (Finland), the life expectancy was the longest. Shortest life expectancy was in Chukotka (62,8 years) (Russian Federation). In general, life expectancy was shorter in the Russian Arctic than in the other Arctic regions because of the high mortality rates, especially among the working age population. The Russian Arctic had much higher rates of deaths from external causes (including accidents, murders, and suicide) than other countries. Moreover, the difference between males’ and females’ life expectancy was significantly higher in the Russian Arctic than in other Arctic regions.

2019 March

- Arctic

- Demography