65 Maps

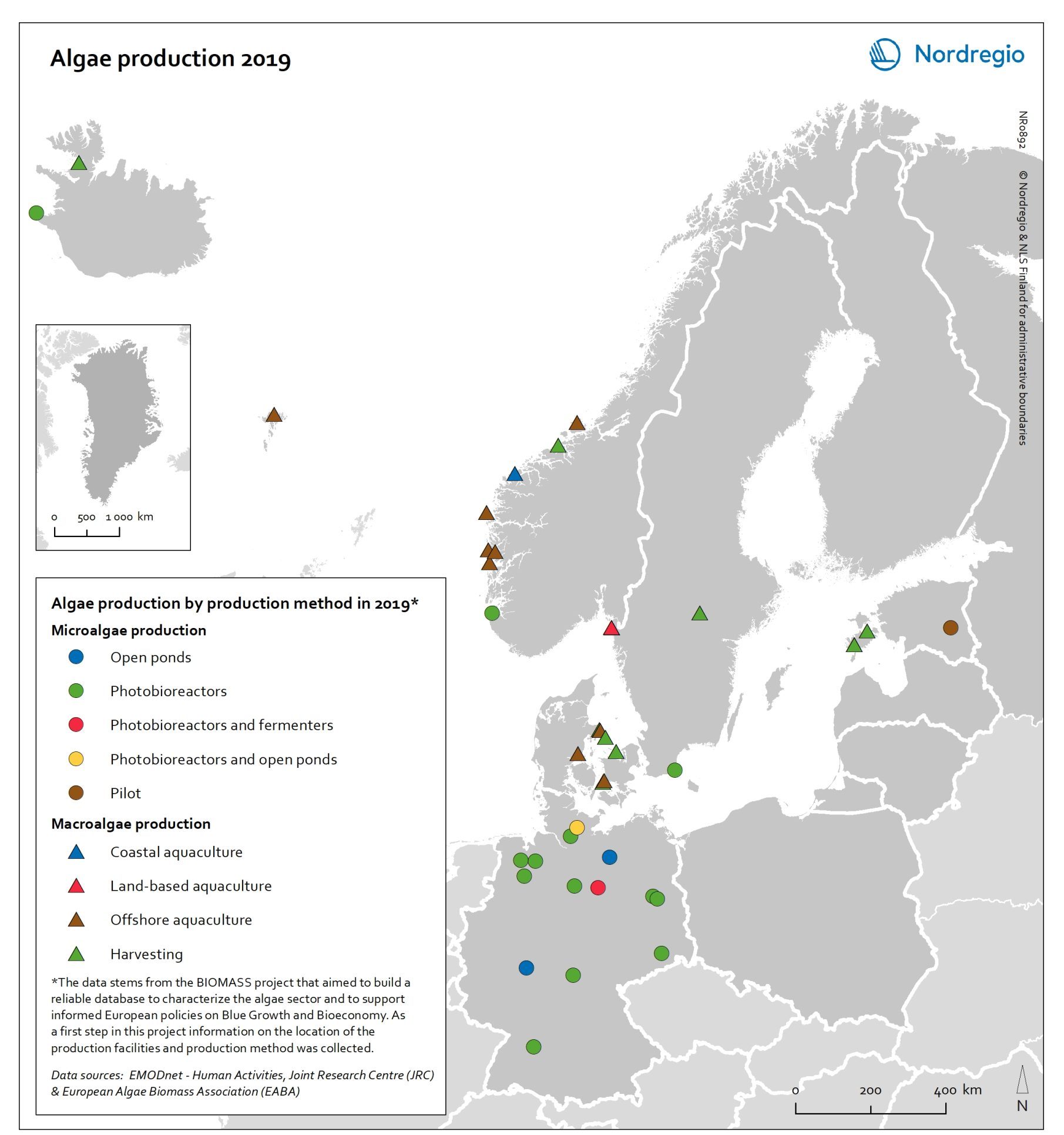

Algae production in 2019

This map shows location of algae production by production method in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2019 Algae and seaweeds are gaining attention as useful inputs for industries as diverse as energy and human food production. Aquatic vegetation – both in the seas and in freshwater – can grow at several times the pace of terrestrial plants, and the high natural oil content of some algae makes them ideal for producing a variety of products, from cosmetic oils to biofuels. At the same time, algae farming has added value in potential synergies with farming on land, as algae farms utilise nutrient run-off and reduce eutrophication. In addition, aquatic vegetation is a highly versatile feedstock. Algae and seaweed thrive in challenging and varied conditions and can be transformed into products ranging from fuel, feeds, fertiliser, and chemicals, to third-generation sugar and biomass. These benefits are the basis for seaweed and algae emerging as one of the most important bioeconomy trends in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea region. The production of algae for food and industrial uses has hence significant potential, particularly in terms of environmental impact, but it is still at an early stage. The production of algae (both micro- and macroalgae) can take numerous forms, as shown by this map. At least nine different production methods were identified in the region covered in this analysis. A total of 41 production sites were operating in Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Germany, and Sweden. Germany has by far the most sites for microalgae production, whereas Denmark and Norway have the most macroalgae sites.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Others

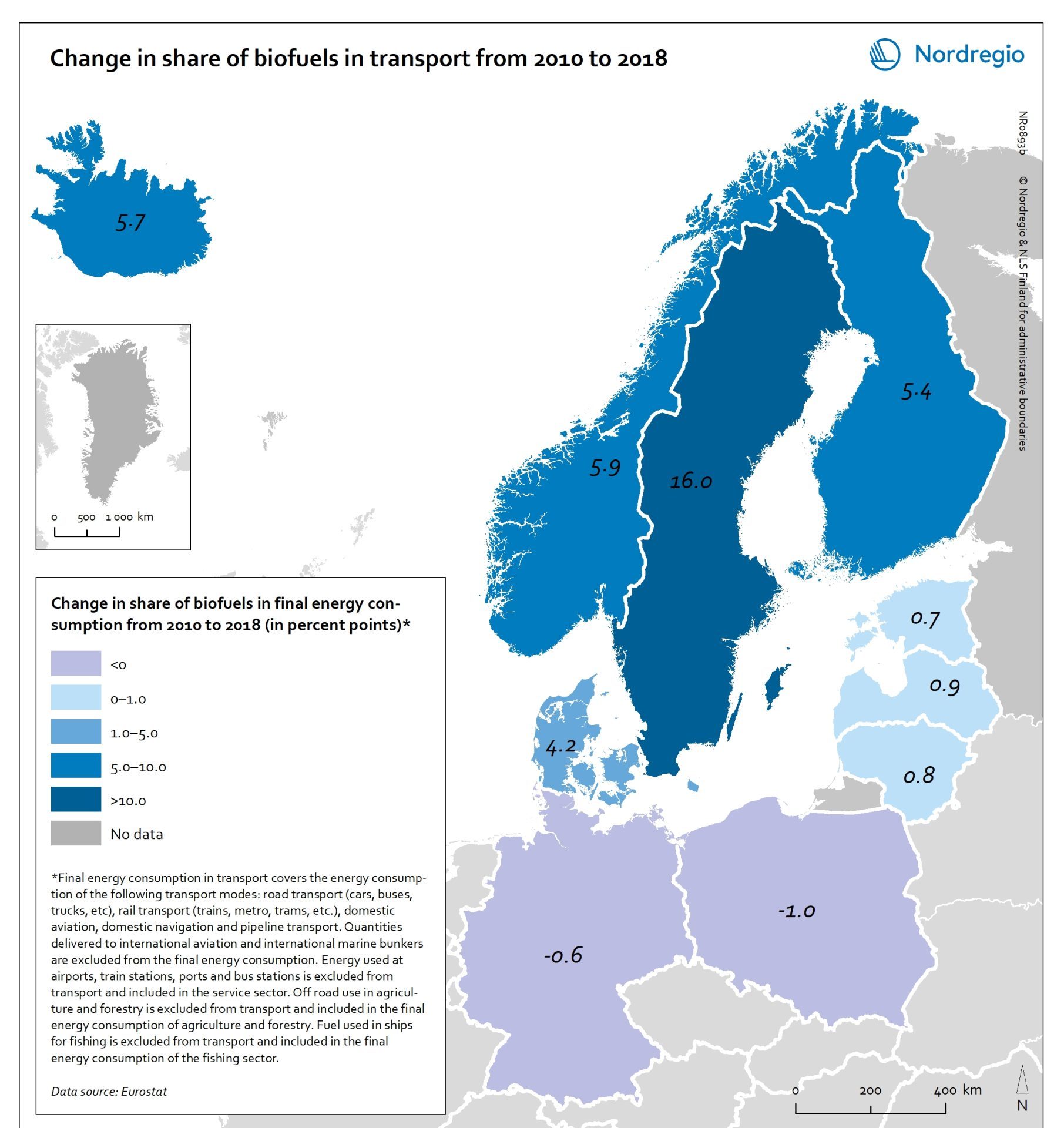

Change in share of biofuels in transport from 2010 to 2018

This map shows change in share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region from 2010 to 2018. Even though a target for greater use of biofuels has been EU policy since the Renewable Energy and Fuel Quality Directives of 2009, development has been slow. The darker shades of blue on the map represent higher increase, and the lighter shades of blue reflect lower increase. The lilac color represent decrease. The Baltic Sea represents a divide in the region, with countries to the north and west experiencing growth in the use of biofuels for transport in recent years. Sweden stands out (16 per cent growth), while the other Nordic countries has experienced more modest increase. In the southern and eastern parts of the region, the use of biofuels for transport has largely stagnated. Total biofuel consumption for transport has risen more than the figure indicates due to an increase in transport use over the period.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

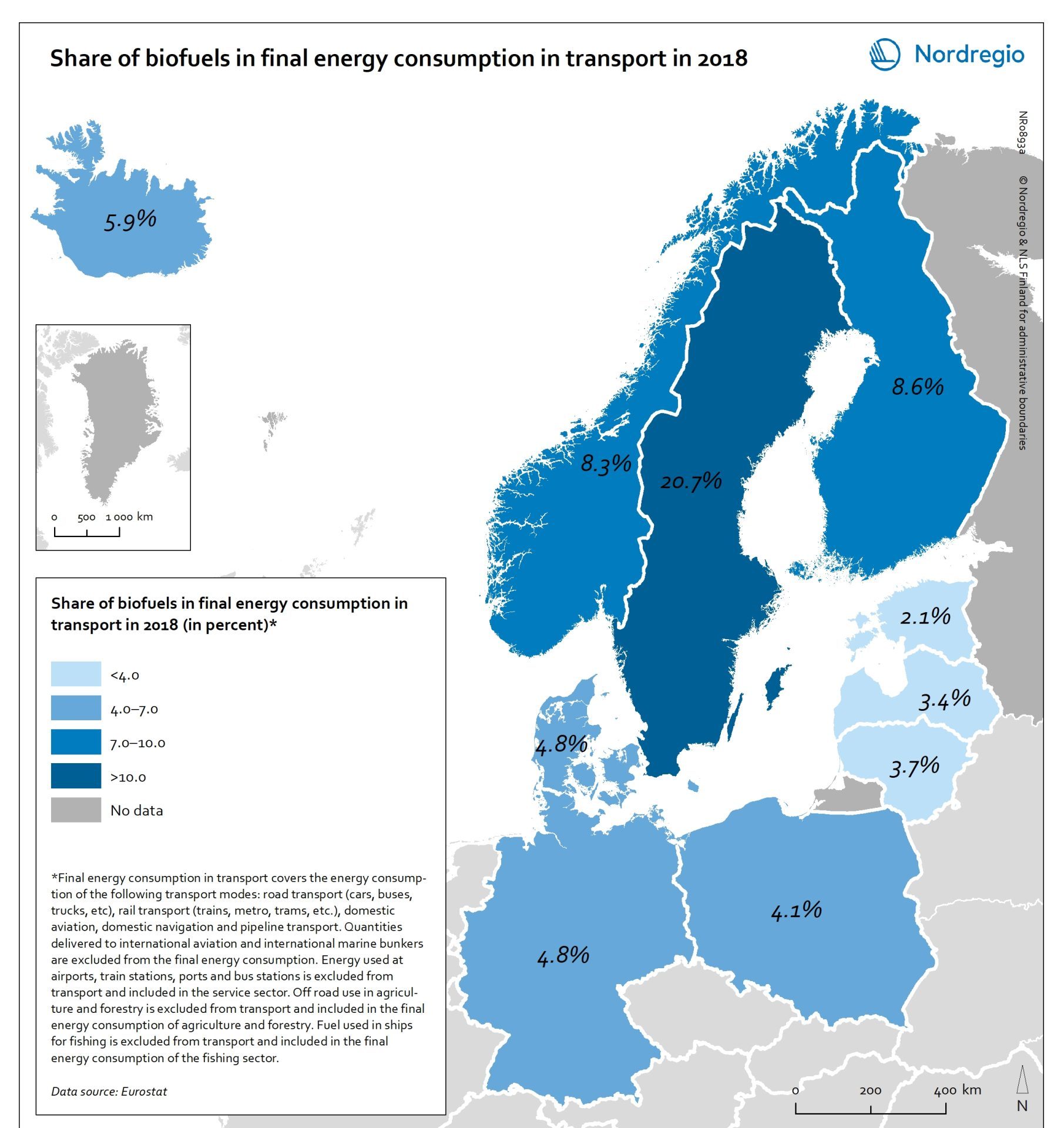

Share of biofuels in transport in 2018

This map shows the share of biofuels in final energy consumption in transport in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2018. There has been considerable political support for biofuels and in the EU, this debate has been driven by the aim of reducing dependency on imported fuels. For instance, 10 per cent of transport fuel should be produced from renewable sources. The darker shades on the map represent higher proportions, and the lighter shades reflect lower proportions. As presented by the map, only Sweden (20.7%) had reached the 10 per cent target in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Region in 2018. Both Finland (8.3%) and Norway (8.3%) were close by the target, while the other countries in the region were still lagging behind, particularly the Baltic countries.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Transport

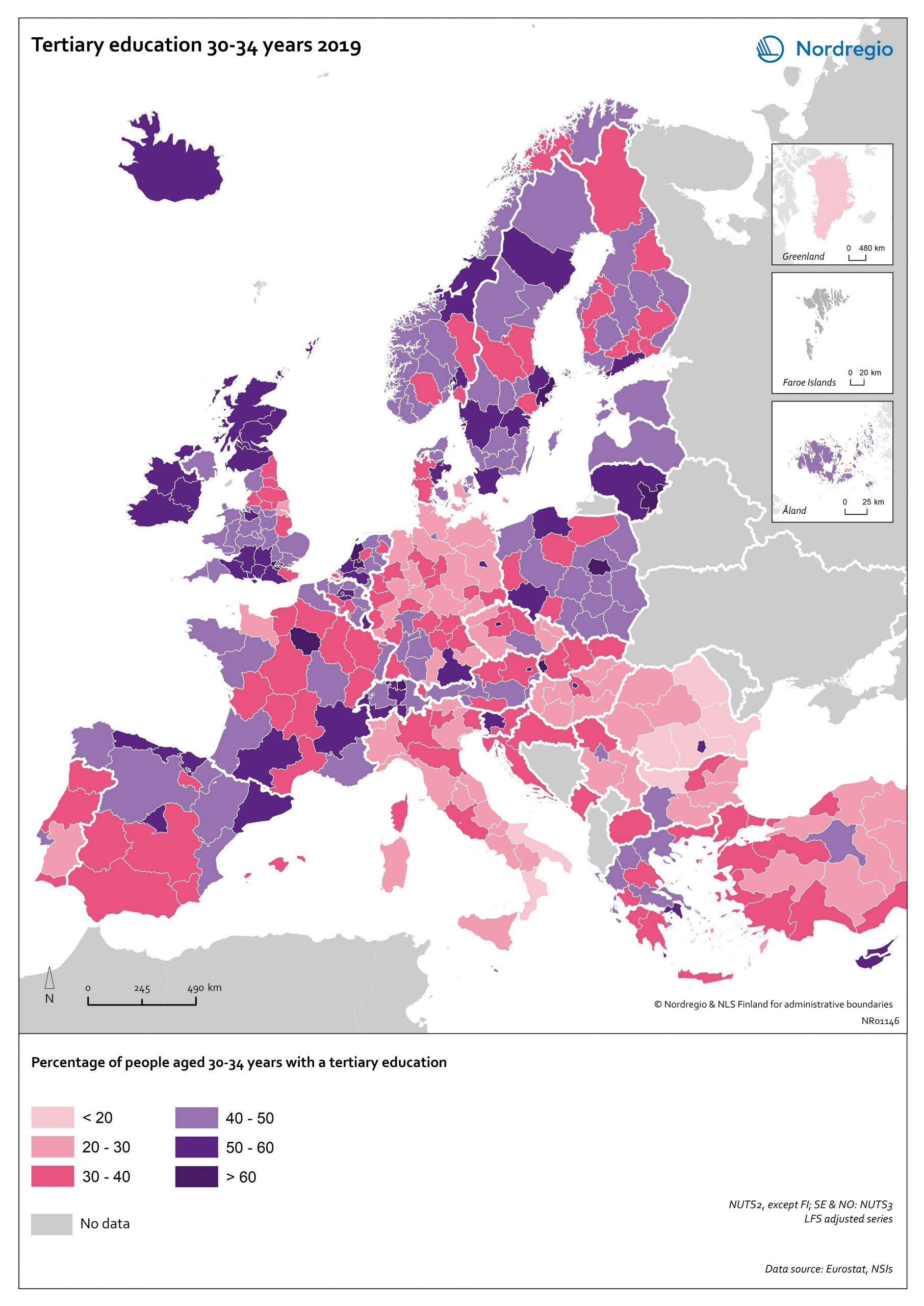

Tertiary education attainment level of 30- to 34-year-olds 2019

The map shows the proportion of the population aged 30-34 years old, who had a tertiary education at the European level in 2019. Purple shades indicate higher proportions, and pinkish shades reflect lower proportions. It is common to show the education attainment for the age group 30-34 since it is an age group where most people have finalised their studies. The focus on this age group makes it easier to see recent trends and outcomes of policies. Overall, over 40% of Europeans aged 30-34 years old had a tertiary education in 2019. Young people in the Nordic countries are among the most educated, with approximately half of 30 to 34-year-olds achieving a tertiary education across all Nordic countries. The highest proportions can be found in the capital regions. Stockholm is particularly noteworthy, with over 60% of 30 to 34-year-olds having had a tertiary education. Regions with prominent universities also stand out – for example, Skåne, Uppsala, Västerbotten and Västra Götaland (Sweden), Trøndelag (Norway) and Østjylland (Denmark).

2020 October

- Baltic Sea Region

- Demography

- Europe

- Nordic Region

- Others

Early leavers from education and training 2016

This map shows the percent of early school leavers in the Nordic Region (NUTS 2 level) and Baltic states in 2016, calculated as the total number of individuals aged 18-24 having a lower secondary education as the highest level attained and not being involved in further education or training. The numbers in each region indicate the proportion of females per 100 males. The yellow/red shading indicates the percent of early school leavers in 2016. The lighter the colour the lower the percentage of early school leavers in 2016. The grey colour indicates no data. Early school leaving is of concern in the Nordic Region to varying degrees. From a pan-European perspective, the Danish (7.2%), Swedish (7.4%) and Finnish (7.9%) averages all fall below the EU average (10.7%) and are in line with the Europe 2020 target of below 10%. The Norwegian average (10.9%) remains slightly above the target but is comparable to the EU average. The average rate of early school leaving in Iceland (19.8%) is substantially higher than the other Nordic countries and the EU average. There is both a spatial and a gender dimension to this problem. The spatial dimension of early school leaving is highlighted in this map, which shows rates of early school leaving in the Nordic Region at the NUTS 2 level. The map highlights the comparatively high rates in Norway, particularly in the north. It is worth noting that, although still high in a Nordic comparative perspective, early school leaving rates have decreased in all Norwegian regions since 2012. Rates are also high in Greenland, with a staggering 57.5% of young people aged 18–24 years who are not currently studying and who have lower secondary as their highest level of educational attainment. The map also shows the gender dimension of early school leaving, with…

2018 February

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Gross Regional Product per capita in million PPP 2015

This map shows the gross regional product per capita in million purchasing power parity (PPP) in all Nordic and Baltic Regions in 2015. The green tones indicate regions with a gross regional product per capita above the EU28 average. The darker the tone the higher the gross regional product per capita. The brown/yellow shading indicates regions with a gross regional product per capita below the EU28 average. The darker the tone the lower the gross regional product per capita. In economic development terms, the Nordic Region continues to perform well in relation to the EU average. Urban and capital city regions still show high levels of GDP per capita reflecting the established pattern throughout Europe. Stockholm, Oslo, Helsinki, Copenhagen and the western Norwegian regions are among the wealthiest in Europe, again confirming that the capital regions and larger cities are the strongest economic centres in the Nordic Region. In addition to these urban regions, some others also display high levels of GRP per capita. What is interesting is that in the aftermath of the economic crisis some second-tier city regions, such as Västra Götaland with Gothenburg in Sweden, are now also displaying fast growth rates as indeed are some less metropolitan regions in the western part of Denmark. These regions display GRP per capita levels which correspond to, or even exceed, those of most metropolitan regions in Europe. most of the central and eastern parts of Finland remain below the EU average.

2018 February

- Baltic Sea Region

- Economy

Saaʹmijânnam – Borders: 1949

The map shows the Skolt Sámi Land and the borders of national states in 1949. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. During the Second World War, the Skolt Sámi land was the stage of violent acts of war. After the war, borders were again redrawn. The Soviet Union took the Petsamo area from Finland. The Skolt Sámi of Petsamo were given new settlement areas in north eastern Finland. In Norway and the Soviet Union, the Skolt Sámi remained an invisible minority. In all three countries, there was very little space for the Sámi. It took decades before the human rights of the Sámi received any attention. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – Borders: 1920

The map shows the Skolt Sámi Land and the borders of national states in 1920. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. The borders through the Skolt Sámi Land were redrawn after the First World War. Newly independent Finland obtained the Petsamo area and thereby access to the Arctic Ocean. The Skolt Sámi living in that area became citizens of Finland instead of Russia. In Norway, the Skolt Sámi suffered from Norwegianization. On the Russian side, the Skolt Sámi were persecuted due to Stalin’s minority group policies. It became difficult to follow seasonal migration routes, a typical of the Skolt Sámi way of life. The Skolt Sámi of Suenjel area were the only ones able to carry out this traditional lifestyle. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

- Migration

Saaʹmijânnam – Borders: 1826

The map shows how the borders of the national states in 1826 divided the Skolt Sámi Land. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. Drawing the borders in 1826 has had a dramatic effect on the Skolt Sámi. Neiden and Pasvik areas were divided between Norway and Russia. The Skolt Sámi lost extensive parts of their living areas and their rights. They became citizens of two countries. Due to a growing number of immigrants, the competition for resources and land increased. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – the History: The monastery of Petsjenga and the fortress of Kola

The map shows the historical Skolt Sámi Land, the monastery of Petsjenga and the fortress of Kola. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. The Russian tsar gave Skolt Sámi areas to the monastery of Petsjenga in 1556. The monastery operated a very successful business in reindeer herding, cooking salt and fishing. Petsjenga and Muetke sijdds were repressed under the monastery’s rule. The tsar had placed his officials at the fortress of Kola, in order to look after his interests in the northern areas. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

- Others

Saaʹmijânnam – the History: Taxation and borders in 14th century

The map shows some of the borders in 14th century around the Skolt Sámi Land. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. In 1326, the treaty of Novgorod led to the Sámi being taxed twofold. The Sámi areas were under pressure from both the east and the west. Karelian and Norwegian settlements spread to the north. Karelians collected taxes from the Sámi, as they themselves were obliged to pay taxes to Novgorod. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – the History: Assumed distribution of ethnic groups around year 500

The map shows the assumed distribution of ethnic groups in Northern Europe around year 500. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps), Martin Skulstad, Rethink. and Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design) and Christian Carpelan (reconstruction of the areas). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – the Community: Location of the Skolt Sámi sijdds with water bodies and elevation

The map shows the location of the seven Skolt Sámi sijjds. The word sijdd refers both to a geographic area and to the people who use it. The Skolt Sámi are an indigenous people with a unique culture and history. In the past, the Skolt Sámi knew exactly which areas belonged to their sijdd. If necessary, the borders of the sijdd could be redrawn by oral agreements. There were strong social ties between the Skolt Sámi areas. Marriages across sijdds were common. In some places, this sijdd system continued until World War II. In the past, the Skolt Sámi moved between several dwelling sites throughout the year. During winter, all the families of the sijdd moved to a common winter settlement. The Skolt Sámi lived on fishing, hunting and gathering. They also kept some reindeer and sheep. The resources of the sijdd were considered collective property, however movables and buildings were owned by individuals. This map shows the water bodies (lakes and rivers) according to their historical extent and location, before they were dammed up or given new courses during the 20th century. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – the Community: Location of the Skolt Sámi sijdds

The map shows the location of the seven Skolt Sámi sijjds. The word sijdd refers both to a geographic area and to the people who use it. The Skolt Sámi are an indigenous people with a unique culture and history. In the past, the Skolt Sámi knew exactly which areas belonged to their sijdd. If necessary, the borders of the sijdd could be redrawn by oral agreements. There were strong social ties between the Skolt Sámi areas. Marriages across sijdds were common. In some places, this sijdd system continued until World War II. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main project page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

Saaʹmijânnam – the Community: Location of the Skolt Sámi Land

The map shows the location of the Skolt Sámi Land. The Skolt Sámi Land is the home area for the indigenous Skolt Sámi people. The Skolt Sámi are an indigenous people with a unique culture and history. Starting in 1826, various state borders were drawn through the Skolt Sámi homeland. Today, at least a thousand people can claim Skolt Sámi ancestry. Most of them are citizens of Norway, Finland and Russia. The Skolt Sámi Land is located in an area which today is divided between Norway, Finland and Russia. The map was produced for the exhibition Saaʹmijânnam – The Skolt Sámi Land in Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum in Neiden, Norway. The map is the result of a collaboration between Äʹvv Skolt Sámi museum (responsible for the reconstruction of the Skolt Sámi areas and the exhibition), Yngvar Julin (concept of maps and exhibition architect), Nordregio (base maps) and Rethink. and illustrator Ruth Thomlevold (graphic design). Back to the main page.

2018 January

- Administrative and functional divisions

- Arctic

NEET rate for young people 18-25 years in 2016

Share of young people aged 18-25 years neither in employment nor in education and training in 2016 There are a range of reasons why a young person may become part of the “NEETs” group, including (but not limited to): complex personal or family related issues; young people’s greater vulnerability in the labour market during times of economic crisis; and the growing trend towards precarious forms of employment for young people. Successful reengagement of these young people with learning and/or the labour market is a key challenge for policy makers and is vital to reducing the risk of long-term unemployment and social exclusion later in life. The map highlights two Polish regions, Podkarpackie and Warminsko-Mazurskie, as having the highest NEET rates in the BSR. High rates can also be found in several other Polish regions as well as the Northern and Eastern Finland Region. The lowest NEET rates in the Baltic Sea Region can be found in the Norwegian Capital Region, followed by several regions in Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

2017 June

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

Youth unemployment rate in 2016

The map highlights two Polish regions, Podkarpackie and Lubuskie, as having the highest youth unemployment rates in the BSR. Several other regions in Poland, along with regions in Northern Finland, Central Sweden and the southernmost Swedish region of Skåne, have also been rather severely hit by youth unemployment. The lowest youth unemployment rates can be found in several Russian regions, among them St. Petersburg, and in regions in Northern Germany and Northern Norway.

2017 June

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

Tertiary education among working-age population, change 2010-2015

The Nordic countries, as well as Estonia and Lithuania, have had among the highest levels of tertiary education in Europe in recent years. This map demonstrates that many regions, particularly those in Poland, are catching up. Several Lithuanian and Latvian regions have also had high rates of positive change between 2010 and 2015. The most modest growth rates, between 0 and 1.5 percent change, were experienced in two Estonian regions, one in Denmark and one in Northern Germany. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Brandenburg, in North-Eastern Germany, were the only regions within the Baltic Sea Region to experience a decrease in the share of working-age persons with tertiary level education from 2010-2015.

2017 March

- Baltic Sea Region

- Labour force

- Nordic Region