206 Maps

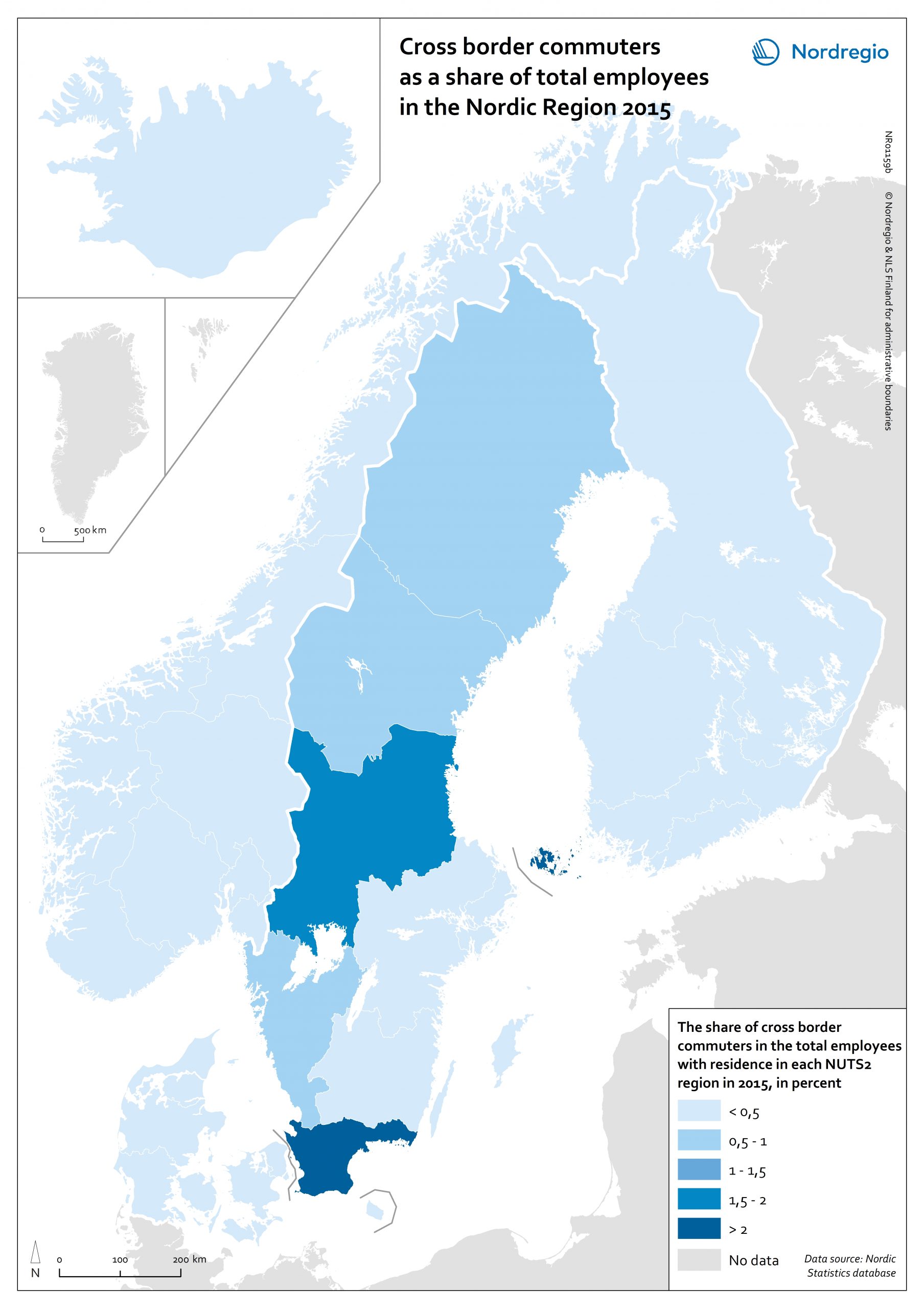

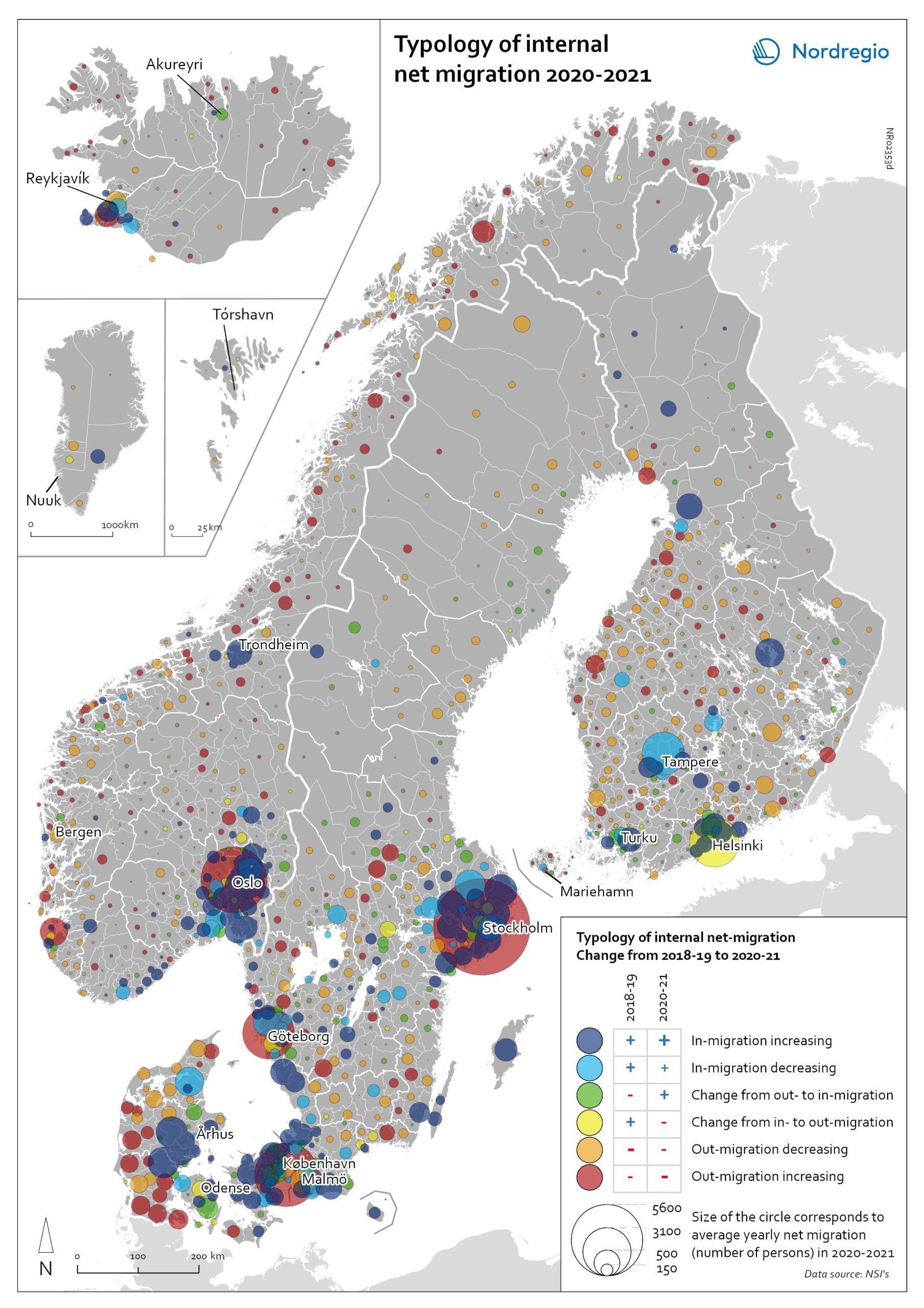

Typology of regional internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration in regions by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019)

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Typology of internal net migration 2020-2021

The map presents a typology of internal net migration by considering average annual internal net migration in 2020-2021 alongside the same figure for 2018-2019. The colours on the map correspond to six possible migration trajectories: Dark blue: Internal net in migration as an acceleration of an existing trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) Light blue: Internal net in migration but at a slower rate than previously (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Green: Internal net in migration as a new trend (net in-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net out-migration compared to 2018-2019) Yellow: Internal net out migration as a new trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + change from net in-migration compared to 2018-2019) Orange: Internal net out migration but at a slower rate than previously (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + decrease compared to 2018-2019) Red: Internal net out migration as a continuation of an existing trend (net out-migration in 2020-2021 + increase compared to 2018-2019) The patterns shown around the larger cities reinforces the message of increased suburbanisation as well as growth in smaller cities in proximity to large ones. In addition, the map shows that this is in many cases an accelerated (dark blue circles), or even new development (green circles). Interestingly, although accelerated by the pandemic, internal out migration from the capitals and other large cities was an existing trend. Helsinki stands out as an exception in this regard, having gone from positive to negative internal net migration (yellow circles). Similarly, slower rates of in migration are evident in the two next largest Finnish cities, Tampere and Turku (light blue circles). Akureyri (Iceland) provides an interesting example of an intermediate city which began to attract residents during the pandemic despite experiencing internal outmigration prior. From a rural perspective there are…

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

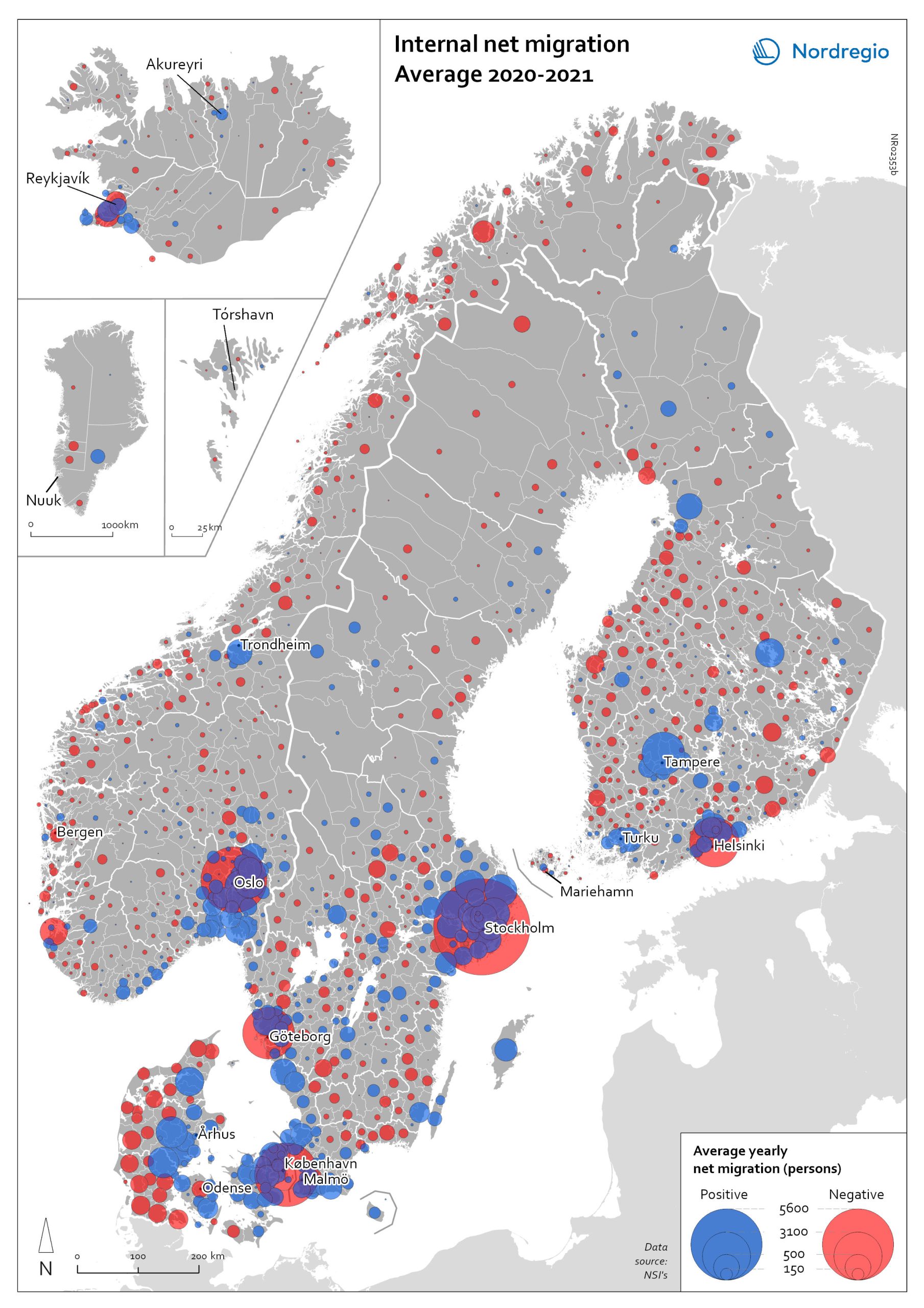

Internal net migration 2020-2021

The map shows the average internal net migration in 2020 and 2021 for Nordic municipalities. Blue dots indicate positive internal net migration (more people moving in than out) and red dots indicate negative internal net migration (more people moving out than in), while the size of the dots represents the extent of the positive or negative trend. Internal migration refers to a change of address within the same country. The map shows substantial outmigration from the Nordic capitals, as well as from Gothenburg and Malmö in Sweden. Alongside increased suburbanisation, the map also provides some evidence of growth in medium-sized cities and smaller cities within commuting distance of larger cities.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

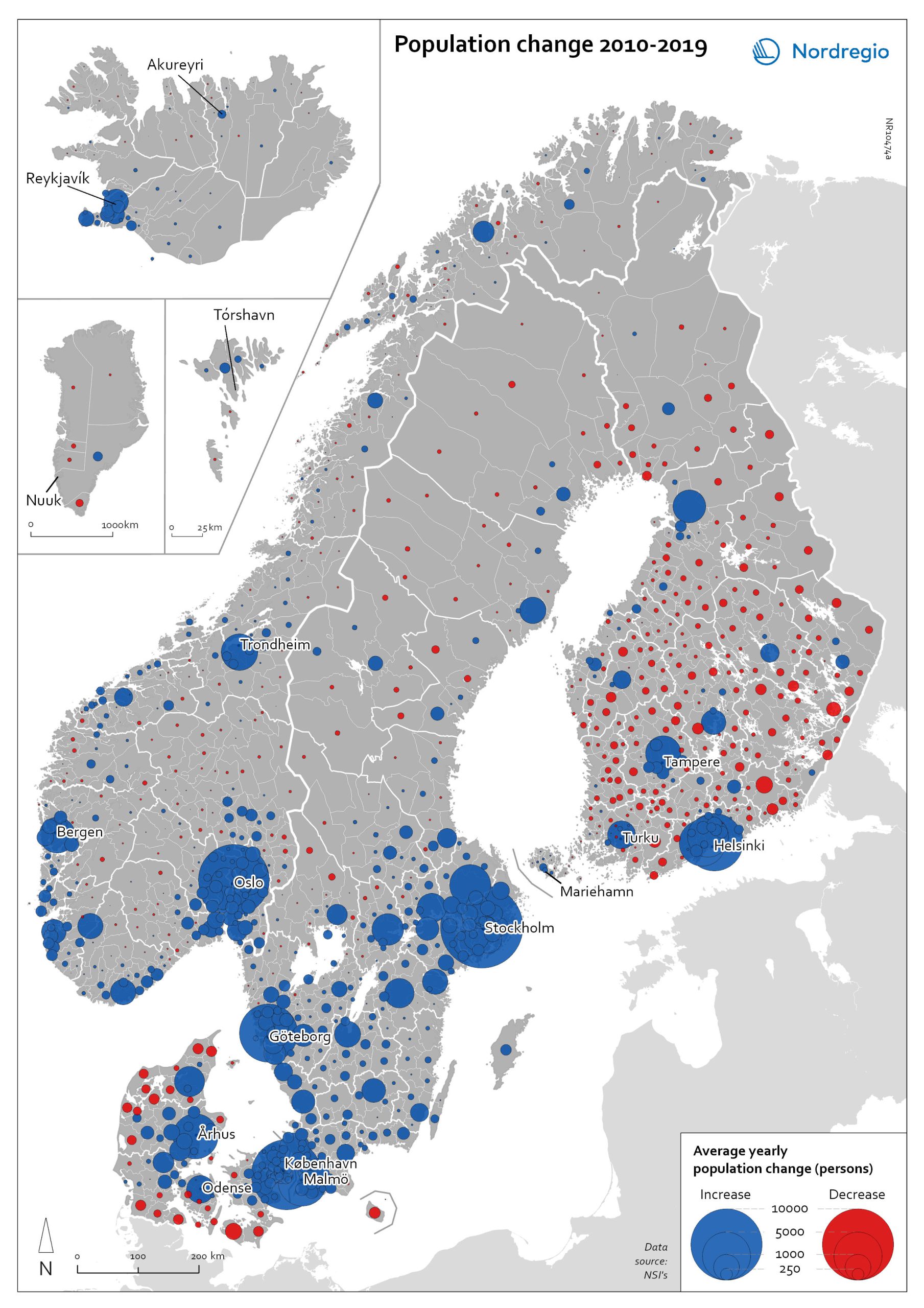

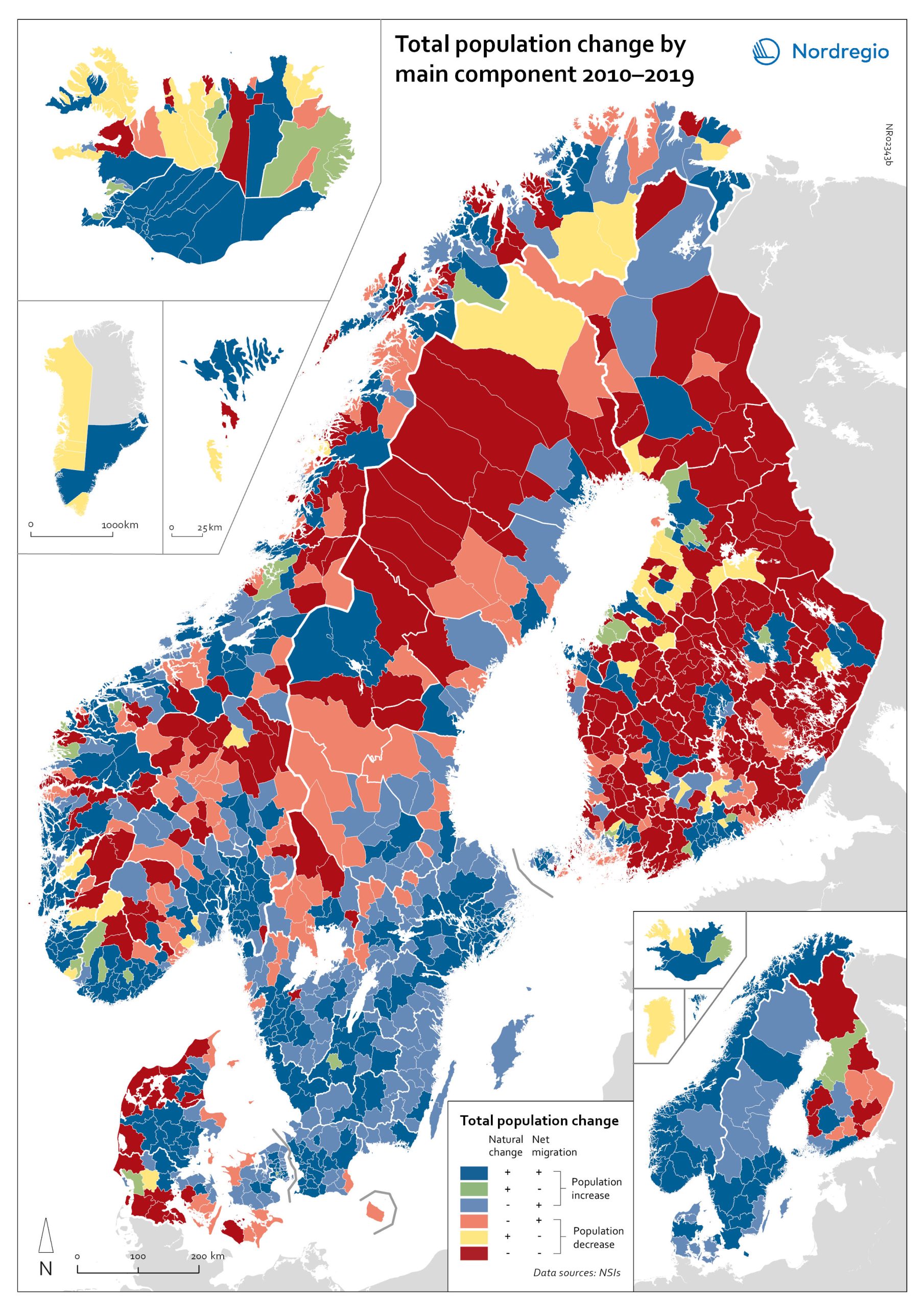

Population change 2010-2019

The map shows the type (positive or negative) and size of population change from 2010 to 2019 in all nordic municipalities. In Finland, Denmark, and Greenland there is a clear pattern of population growth in and around the larger cities and population decline in rural areas. Geographical and administrative differences mean that a much larger number of rural municipalities in Finland are dealing with population decline. Sweden experienced substantial population growth between 2010 and 2019, primarily due to high levels of international immigration. As a result, many rural areas also experienced population growth, particularly in the south of Sweden. However, in the more sparsely populated municipalities in the north of Sweden, the pattern is somewhat similar to that observed in Denmark and Finland, albeit with population decline in lower absolute numbers. Both Iceland and the Faroe Islands experienced substantial growth of their tourism industries within the period. This enabled some rural areas to maintain or even grow their populations. Norway exhibits more balanced population development in general, with a mix of population growth and decline in rural areas throughout the country.

2022 May

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

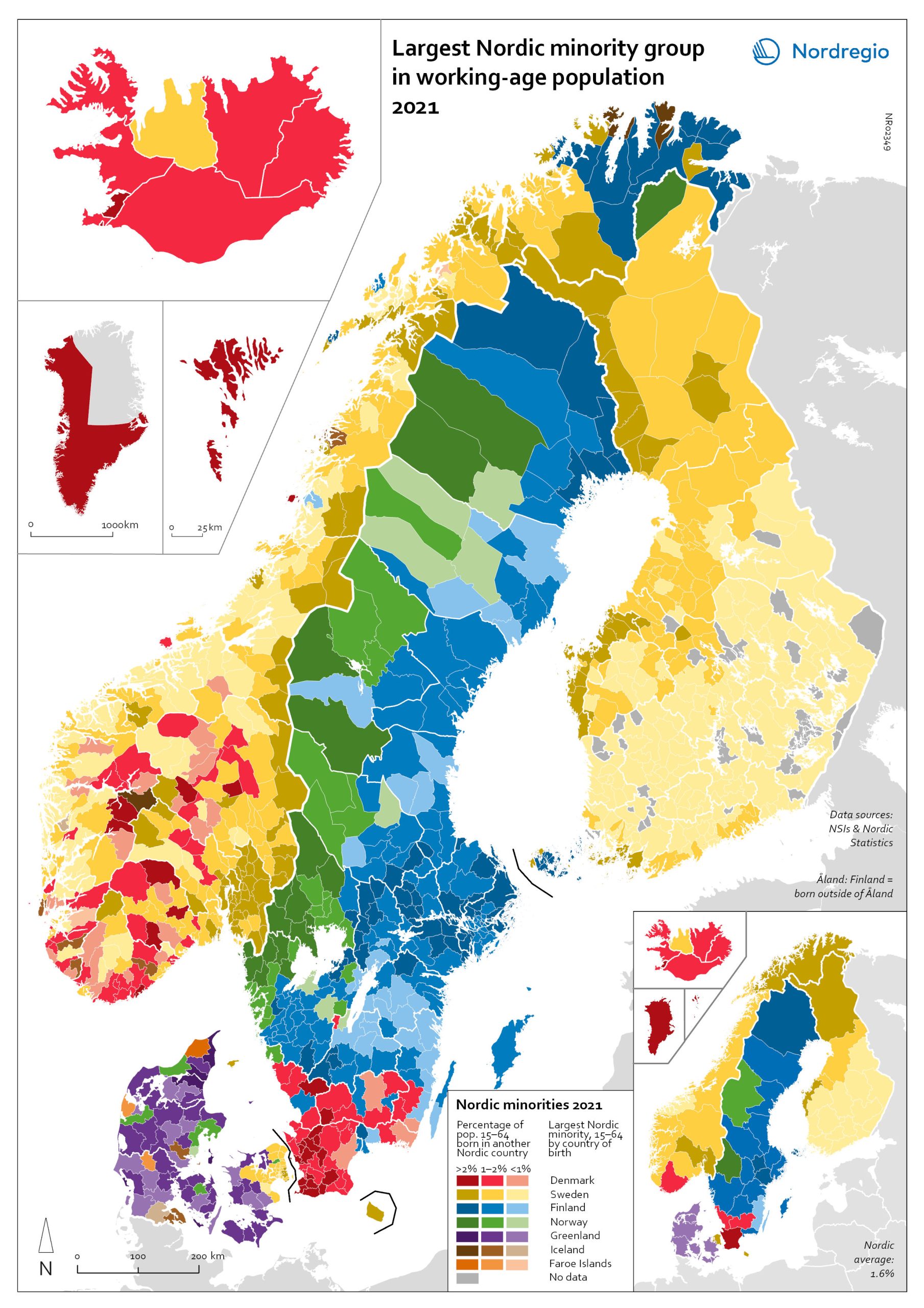

Largest Nordic minority 2021

The map shows the largest Nordic-born minority group at the municipal level among the working-age population (15-64 years old). The intensity of the colour shows the share of the total foreign-born Nordic population, with darker tints indicating a larger percentage than lighter tints. The map illustrates differences at the regional and municipal levels within the countries. For example, while the largest minority in Norway are born in Sweden, those born in Denmark constitute the largest minority Nordic-born group in the southern Norwegian region of Agder. The largest Nordic-born minority in Denmark are those born in Sweden in absolute numbers and in the capital region of Hovedstaden, while the largest minority in all other Danish regions is from Greenland. In Sweden, the largest Nordic-born minority overall are from Finland, but there are also regional differences here: in the regions of Skåne, Halland and Kronoberg, the largest Nordic minority group come from Denmark, and in Värmland and Jämtland-Härjedalen, the largest is Norwegian born. In the cross-border municipalities, this pattern is even more accentuated and made evident in areas such as Haparanda in Sweden (the twin city of Tornio in Finland) where 26.5% of the population is Finnish born. Åland has the highest share of other Nordic nationals, where, for example, 47% of the population in the municipality of Kökar is born in a different Nordic country (including Finnish born). Excluding the municipalities of Åland, Haparanda is the municipality in which Nordic-born minorities make up the highest percentage of the total working-age population.

2022 March

- Demography

- Nordic Region

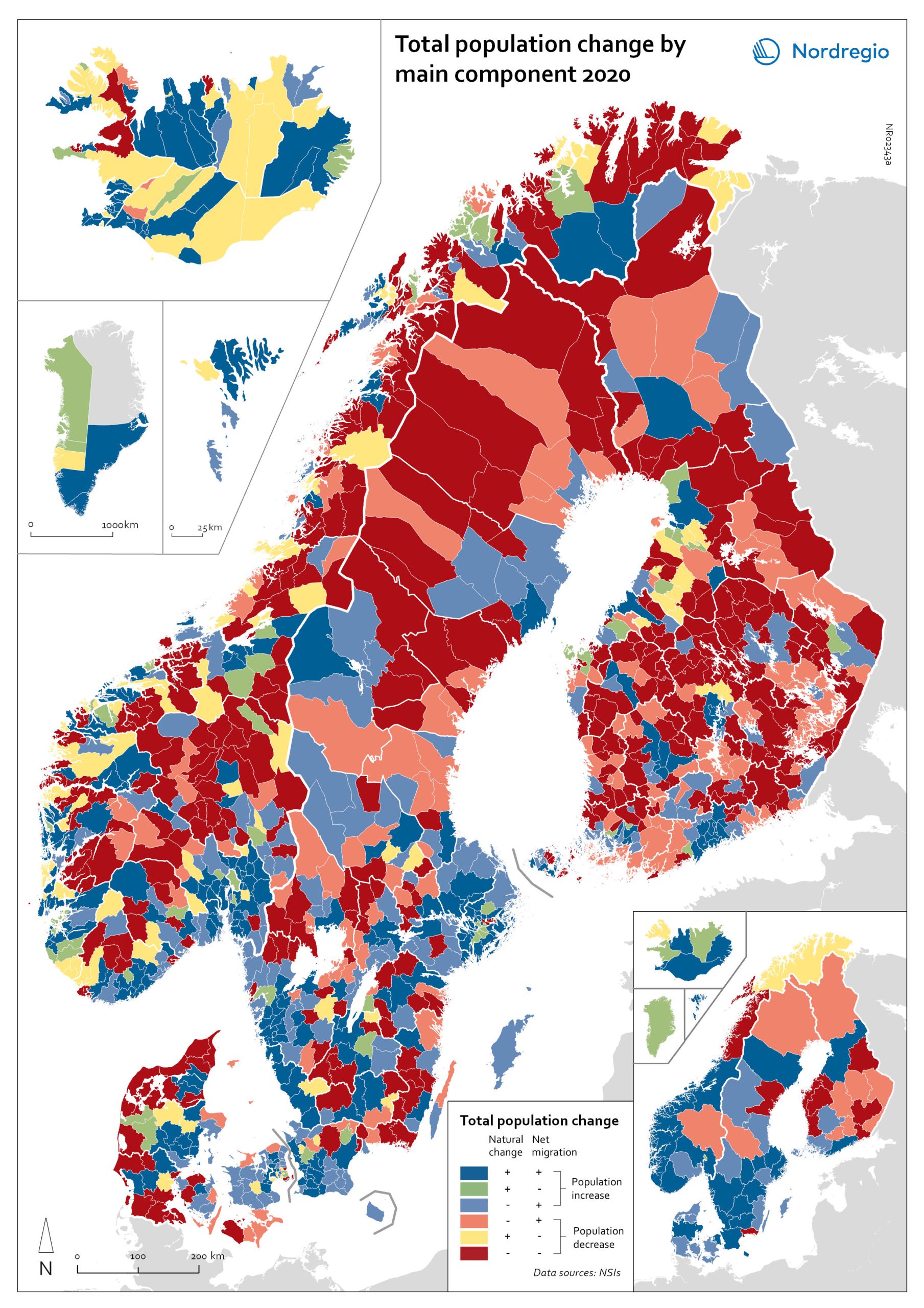

Population change by component 2020

The map shows the population change by component 2020. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2010-2019. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Population change by component 2010-2019

The map shows the population change by component 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing regional and municipal patterns in population change by component in 2020. Regions are divided into six classes of population change. Those in shades of blue or green are where the population has increased, and those in shades of red or yellow are where the population has declined. At the regional level (see small inset map), all in Denmark, all in the Faroes, most in southern Norway, southern Sweden, all but one in Iceland, all of Greenland, and a few around the capital in Helsinki had population increases in 2010-2019. Most regions in the north of Norway, Sweden, and Finland had population declines in 2010-2019. Many other regions in southern and eastern Finland also had population declines in 2010-2019, mainly because the country had more deaths than births, a trend that pre-dated the pandemic. In 2020, there were many more regions in red where populations were declining due to both natural decrease and net out-migration. At the municipal level, a more varied pattern emerges, with municipalities having quite different trends than the regions of which they form part. Many regions in western Denmark are declining because of negative natural change and outmigration. Many smaller municipalities in Norway and Sweden saw population decline from both negative natural increase and out-migration despite their regions increasing their populations. Many smaller municipalities in Finland outside the three big cities of Helsinki, Turku, and Tampere also saw population decline from both components. A similar pattern took place at the municipal level in 2020 of there being many more regions in red than in the previous decade.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

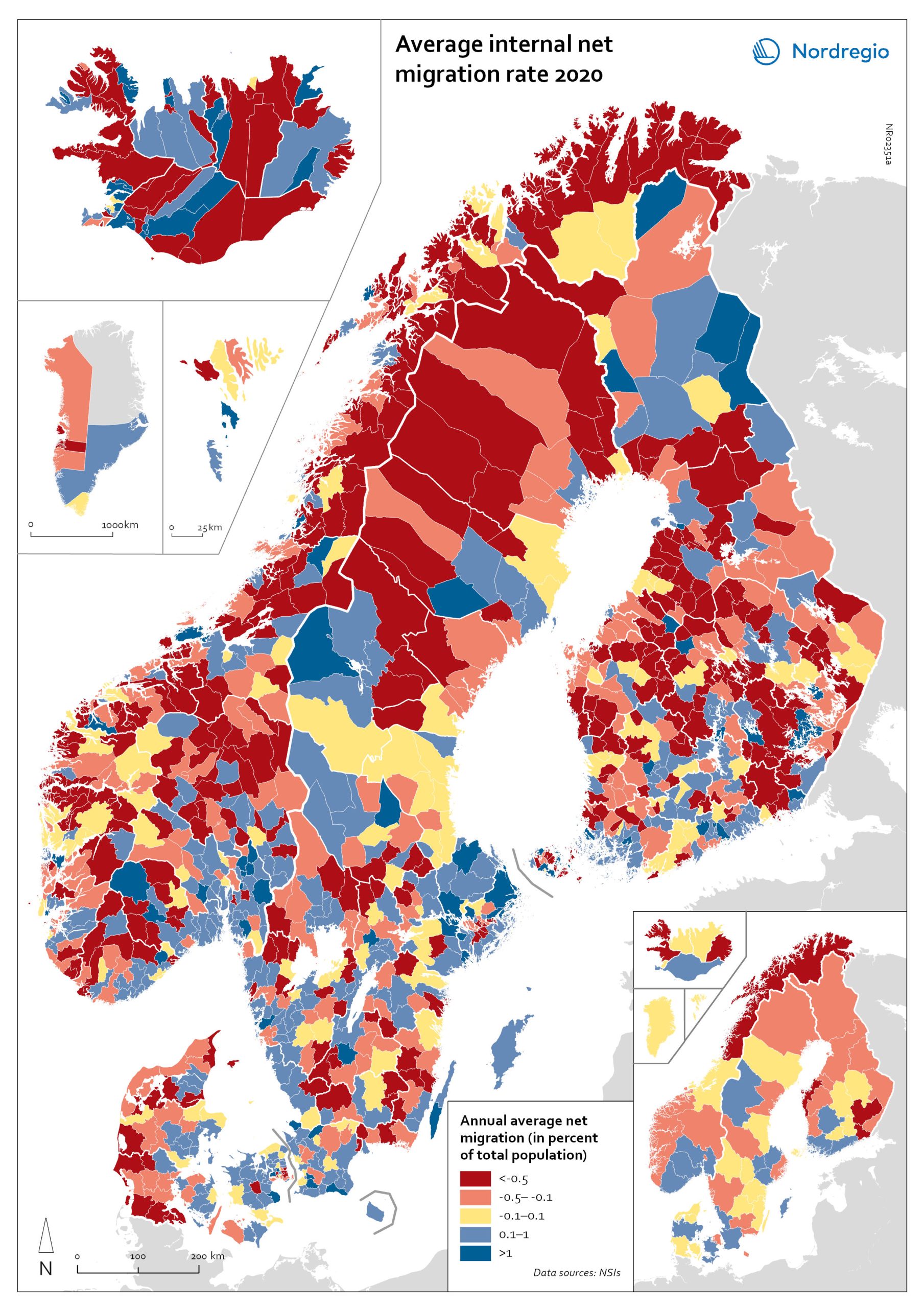

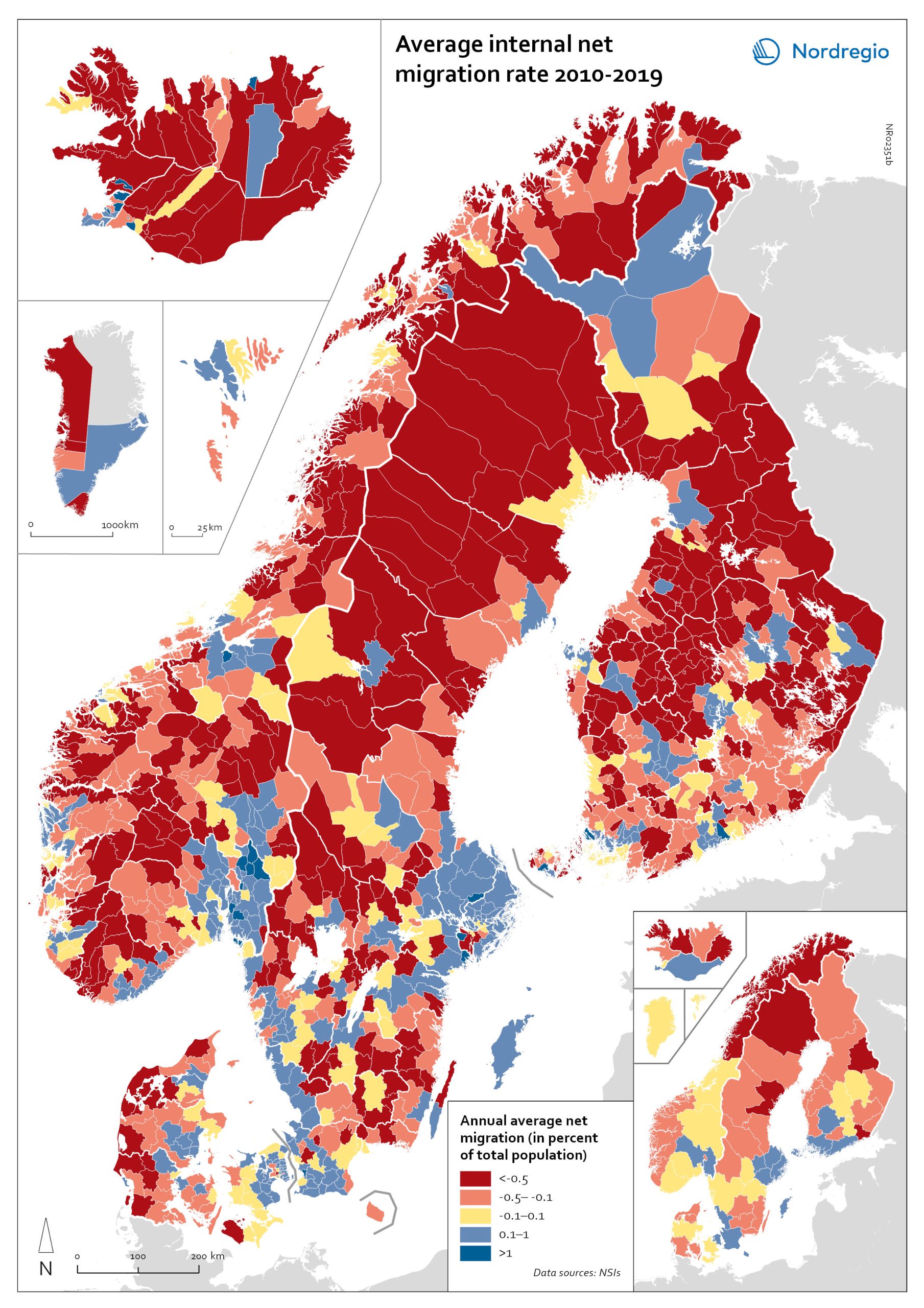

Net internal migration rate 2020

The map shows the internal net migration in 2020. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2010-2019. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who decide to…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Net internal migration rate, 2010-2019

The map shows the annual average internal net migration in 2010-2019. The map is related to the same map showing net internal migration in 2020. The maps show several interesting patterns, suggesting that there may be an increasing trend towards urban-to-rural countermigration in all the five Nordic countries because of the pandemic. In other words, there are several rural municipalities – both in sparsely populated areas and areas close to major cities – that have experienced considerable increases in internal net migration. In Finland, for instance, there are several municipalities in Lapland that attracted return migrants to a considerable degree in 2020 (e.g., Kolari, Salla, and Savukoski). Swedish municipalities with increasing internal net migration include municipalities in both remote rural regions (e.g., Åre) and municipalities in the vicinity of major cities (e.g., Trosa, Upplands-Bro, Lekeberg, and Österåker). In Iceland, there are several remote municipalities that have experienced a rapid transformation from a strong outflow to an inflow of internal migration (e.g., Ásahreppur, Tálknafjarðarhreppurand, and Fljótsdalshreppur). In Denmark and Norway, there are also several rural municipalities with increasing internal net migration (e.g., Christiansø in Denmark), even if the patterns are somewhat more restrained compared to the other Nordic countries. Interestingly, several municipalities in capital regions are experiencing a steep decrease in internal migration (e.g., Helsinki, Espoo, Copenhagen and Stockholm). At regional level, such decreases are noted in the capital regions of Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Stockholm. At the same time, the rural regions of Jämtland, Kalmar, Sjælland, Nordjylland, Norðurland vestra, Norðurland eystra and Kainuu recorded increases in internal net migration. While some of the evolving patterns of counterurbanisation were noted before 2020 for the 30–40 age group, these trends seem to have been strengthened by the pandemic. In addition to return migration, there may be a larger share of young adults who…

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

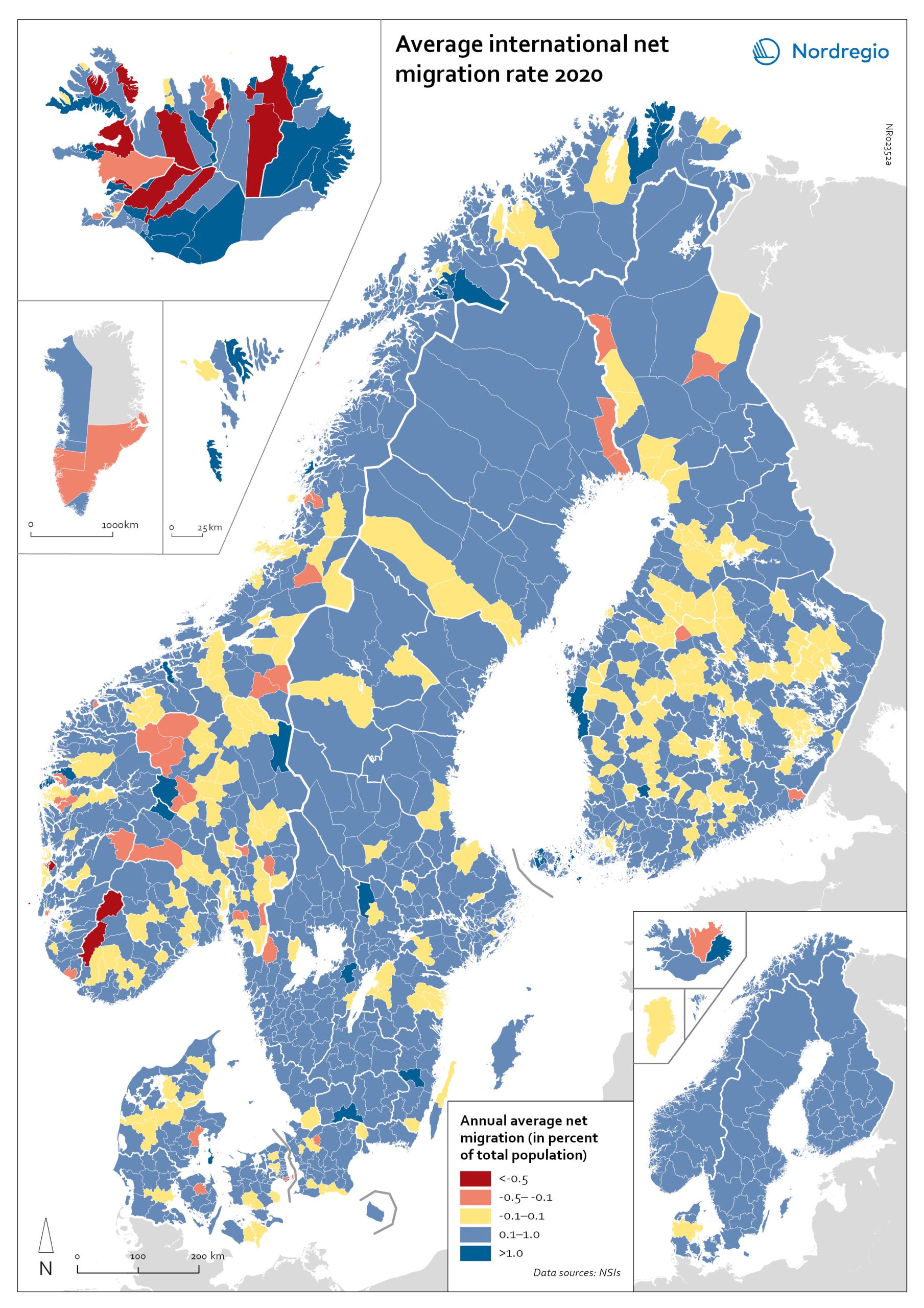

Net international migration rate, 2020

The map shows the international net migration in 2020. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2010-2019. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

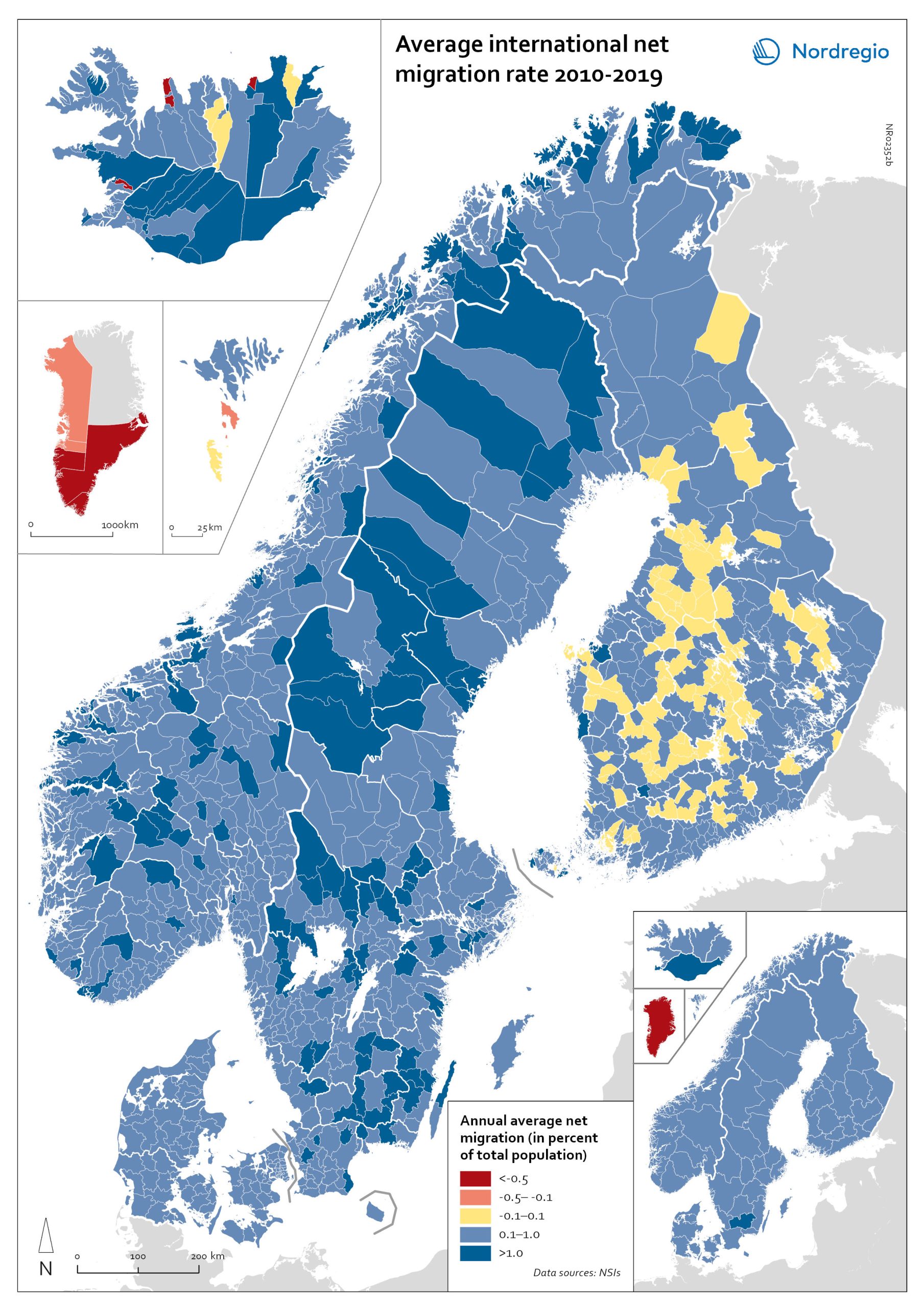

Net international migration rate, 2010–2019

The map shows the annual average international net migration from 2010 to 2019. The map is related to the same map showing net migration in 2020. At regional level, there are only minor changes between the net migration in 2010-2019 and 2020. All regions of Norway, all regions of Sweden except Gotland and Uppsala, and the regions of Österbotten in Finland, Midtjylland in Denmark and Norðurland eystra in Iceland experienced a slight decrease in international net migration I 2020 compared to 2010-2019. There is a more marked increase in net migration in the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the region of Norðurland vestra in Iceland, and a slight increase in the region of Austurland in Iceland. At municipal level, the maps show more changing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and Sweden, several municipalities – both in the capital, intermediate, and rural regions – had lower levels of international net migration in 2020 compared to 2010-2019. In Iceland and Finland, the picture is more balanced, with some municipalities showing a decrease, others an increase. In the Faroe Islands and Greenland, several municipalities/regions had an increase in international net migration.

2022 March

- Demography

- Migration

- Nordic Region

Natural population change in the Nordic Region 2021

The map shows the natural population change in the Nordic Region from January to September 2021 While all Nordic countries except Finland were characterised by positive natural population change during 2021, this growth was often particularly pronounced in and around cities and towns, with their relatively youthful populations. Urban centres and their surrounding areas such as Stockholm and Malmö in Sweden, Oslo and Trondheim in Norway, Espoo and Helsinki in Finland or Aarhus and Copenhagen in Denmark all reported among the highest rates of natural population growth during the first nine months of 2021. Rural regions with their often-older population age structures were more likely to experience natural population decline, a pattern that had already existed prior to the pandemic. Especially in Finland, many rural municipalities reported high natural population decline during the first nine months of 2021, despite increases in the number of births, as shown in the map “Change in the number of births in the Nordics”. In the other Nordic countries, only a few municipalities experienced similarly high levels of natural population decline.

2022 March

- Demography

- Nordic Region

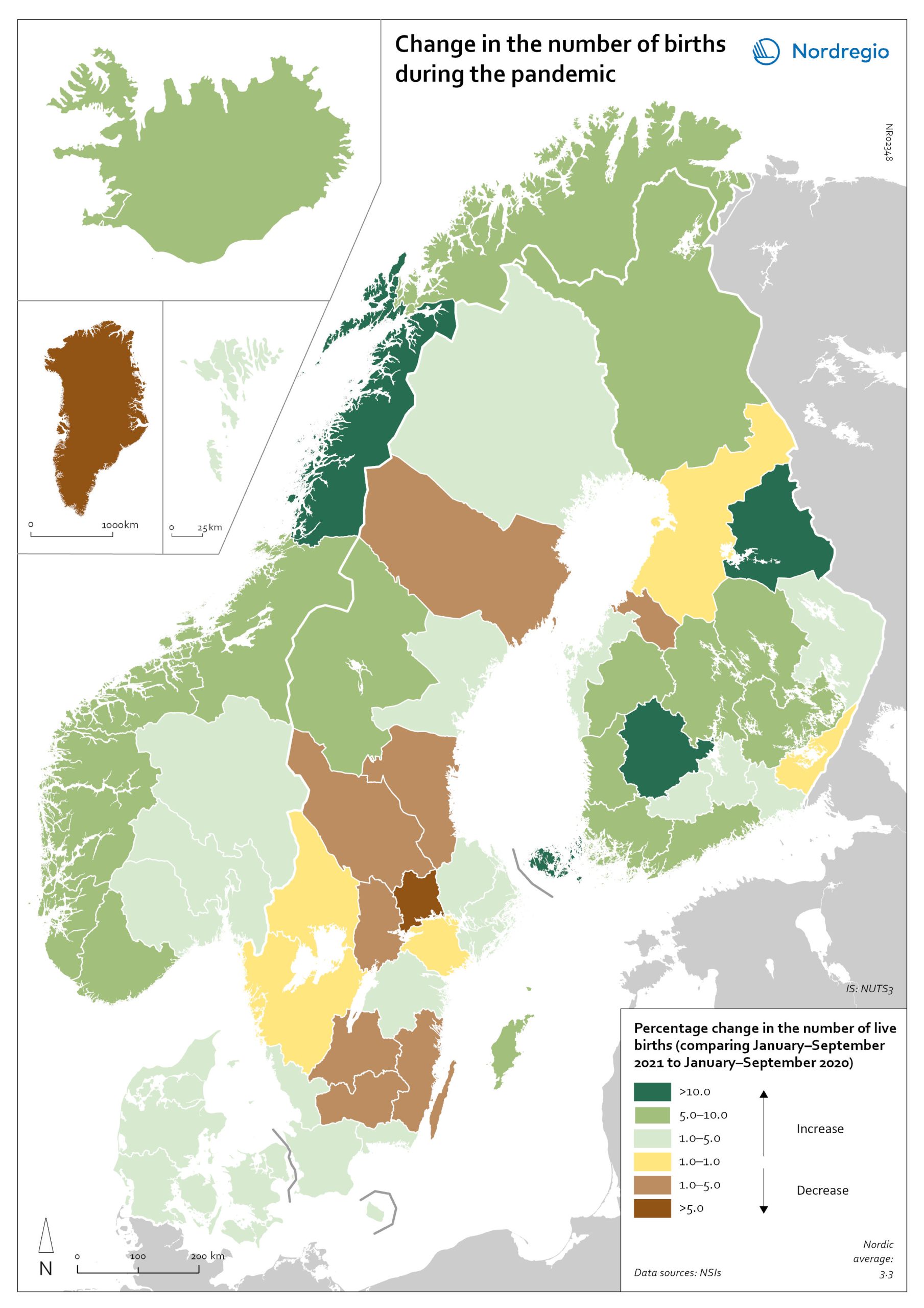

Change in the number of births in the Nordics

The map shows percentage change in the number of live births in Nordic regions, comparing January-September 2021 to the same period in 2020. While most Nordic countries and autonomous territories saw a rise in births during the pandemic, not all regions followed this trend to the same extent. Rural regions stand out as having had both baby booms and baby busts during the pandemic. In Finland, for example, rural regions reported both large increases in births (Kainuu) but also declines (Central Ostrobothnia). In Sweden, only a few regions registered an increase in the number of babies conceived during the pandemic; among those were rural Gotland and Jämtland. Kronoberg and Dalarna, by contrast, reported a drop of more than 3% in the number of births.

2022 March

- Demography

- Nordic Region

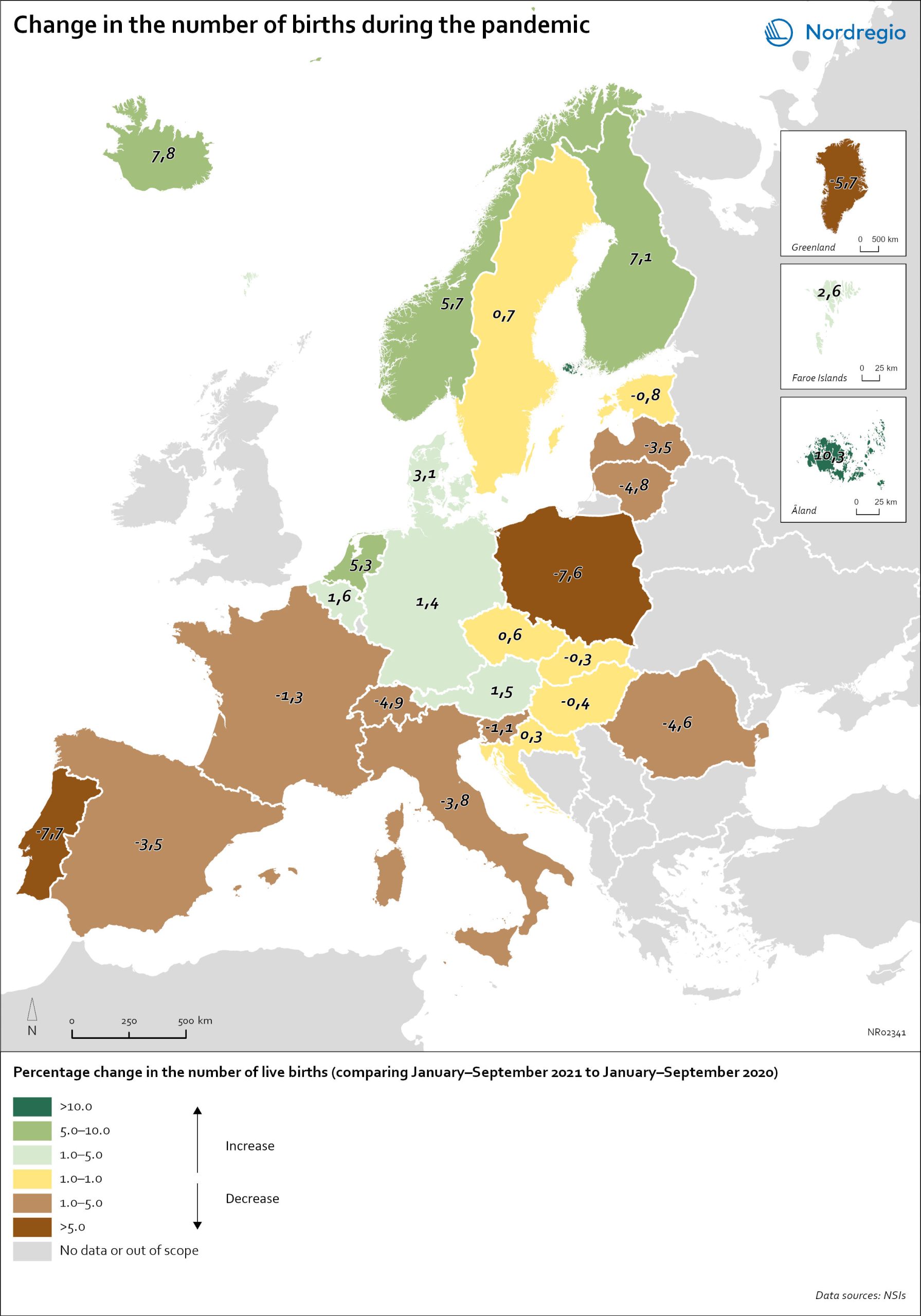

Change in the number of births in Europe

The map shows the number of births during the first nine months of 2021 (January to September) compared to the number of births during the same months in 2020. The babies born during the first nine months of 2021 were conceived between the spring and winter of 2020 when the first waves of the pandemic affected Europe. Babies born during the first nine months of 2020 were conceived in 2019 (i.e., before the pandemic). The map therefore compares the number of births conceived before and during the pandemic. At the time of writing, it seems as if both baby boom and baby bust predictions have been correct, with developments playing out differently across countries. In many Southern and Eastern European countries, such as Spain, Italy or Romania, the number of births declined by more than 1% during the first nine months of 2021. In Portugal and Poland, but also Greenland, drops in the number of births were particularly sharp with more than 5% fewer babies born in 2021. In several of these “baby bust” countries, these decreases in fertility came on top of already low fertility rates. Spain, Italy, Portugal and Poland, for instance, all already had a total fertility rate (TFR) of less than 1.5 children per woman before the crisis. These values are substantially below the so-called ‘replacement ratio’ of 2.1 children per woman, which is necessary to maintain population size. In these countries, existing demographic challenges have thus been aggravated during the pandemic.

2022 March

- Demography

- Europe

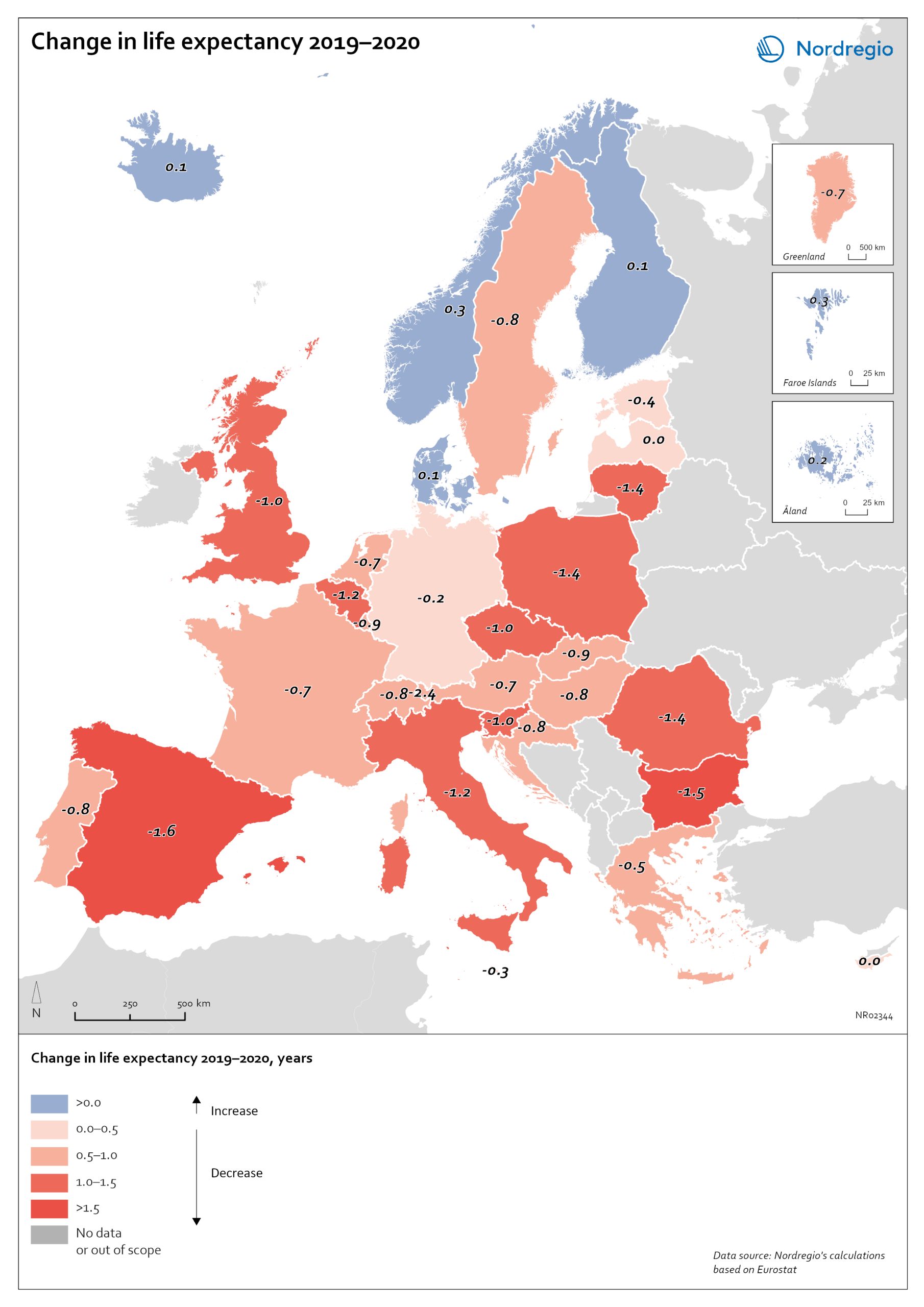

Change in life expectancy 2019–2020 by country in Europe

The excess mortality has affected overall life expectancy at birth across Europe. In 2019, prior to the start of the pandemic, Spain, Switzerland, and Italy had the highest life expectancy in Europe, followed closely by Sweden, Iceland, France, and Norway. Finland and Denmark had slightly lower levels but were still at or above the EU average (Eurostat, 2021). Life expectancy across the EU as a whole and in nearly all other countries has been steadily increasing for decades. Declines in life expectancy are rare, but that is indeed what happened in many countries in Europe during the pandemic in 2020. One study of upper-middle and high-income countries showed that life expectancy declined in 31 of 37 countries in 2020. The only countries where life expectancy did not decline were New Zealand, Taiwan, Iceland, South Korea, Denmark and Norway. The largest falls were in Russia and the United States. The high excess mortality in Sweden in 2020 has had an impact on life expectancy. In Iceland, Norway, Finland, Denmark and the Faroe Islands, life expectancy went up for both sexes in 2020 (data not yet available for Greenland and Åland). In Sweden, life expectancy fell by 0.7 years for males from 81.3 years to 80.6 and for females by 0.4 years from 84.7 to 84.3 years. The steeper decline in life expectancy for males is consistent with the larger number of excess deaths among males. Thus, compared to other Nordic countries, the adverse mortality impact of the pandemic has been greater in Sweden. However, when comparing Sweden to the rest of Europe, it is the Nordic countries, other than Sweden, which are exceptional. The trend among countries in Europe is for a fall in life expectancy in 2020. The largest declines were in countries in southern and eastern Europe. Italy and…

2022 March

- Demography

- Europe

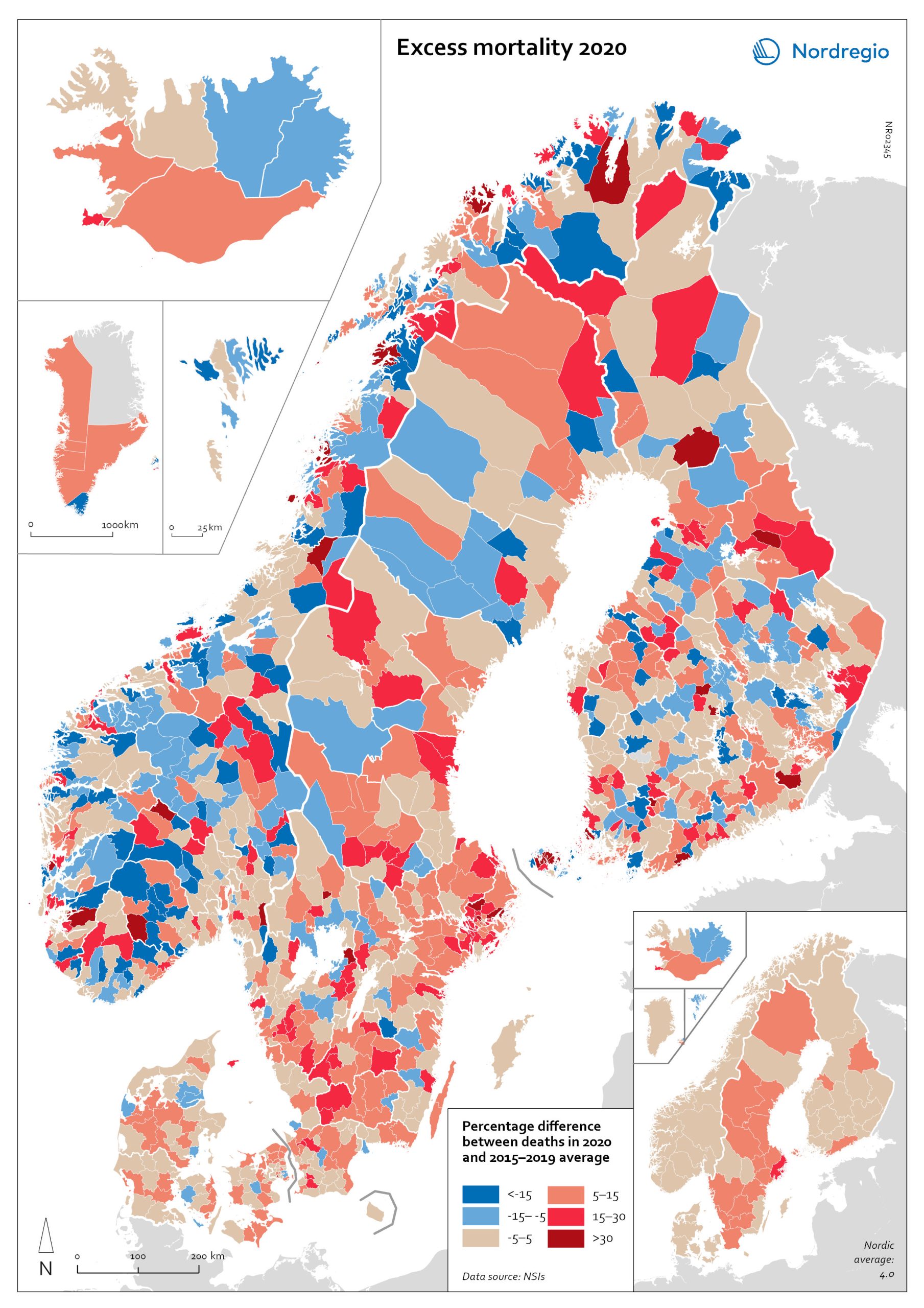

Excess mortality by region

The map shows the relative change in number of deaths in 2020 compared to average 2015-2019. Municipalities in various shades of blue had lower mortality in 2020 than the 2015–2019 average, while municipalities in pink and shades of red had higher mortality. Those in beige are where mortality was mostly unchanged in 2020. In Sweden, many municipalities in the south had excess mortality. Noticeable is a ring of municipalities surrounding Stockholm with excess mortality. During the first two months of the pandemic, March-May 2020, there were 2110 excess deaths in the Stockholm Region (Calderón-Larrañaga, o.a., 2020). Many of these occurred in distant suburbs with high shares of socioeconomically deprived populations (Sigurjónsdóttir, Sigvardsson, & Oliveira e Costa, 2021). There was a disproportionate impact of Covid–19 in Stockholm (Kolk, Drefahl, Wallace, & Andersson, 2021). Denmark had a mix of municipalities with slight excess mortality, slight mortality deficits, or little change, consistent with having very moderate excess mortality overall. Finland showed a similar pattern, with some municipalities recording excess mortality and others mortality deficits. Consistent with having no excess mortality, Norway had many regions with moderate or significant mortality deficits and only a few areas with high amounts of excess mortality. In Iceland, except for one small region near the capital, there was not much difference between the Greater Reykjavík Area and the rest of the country.

2022 March

- Demography

- Nordic Region

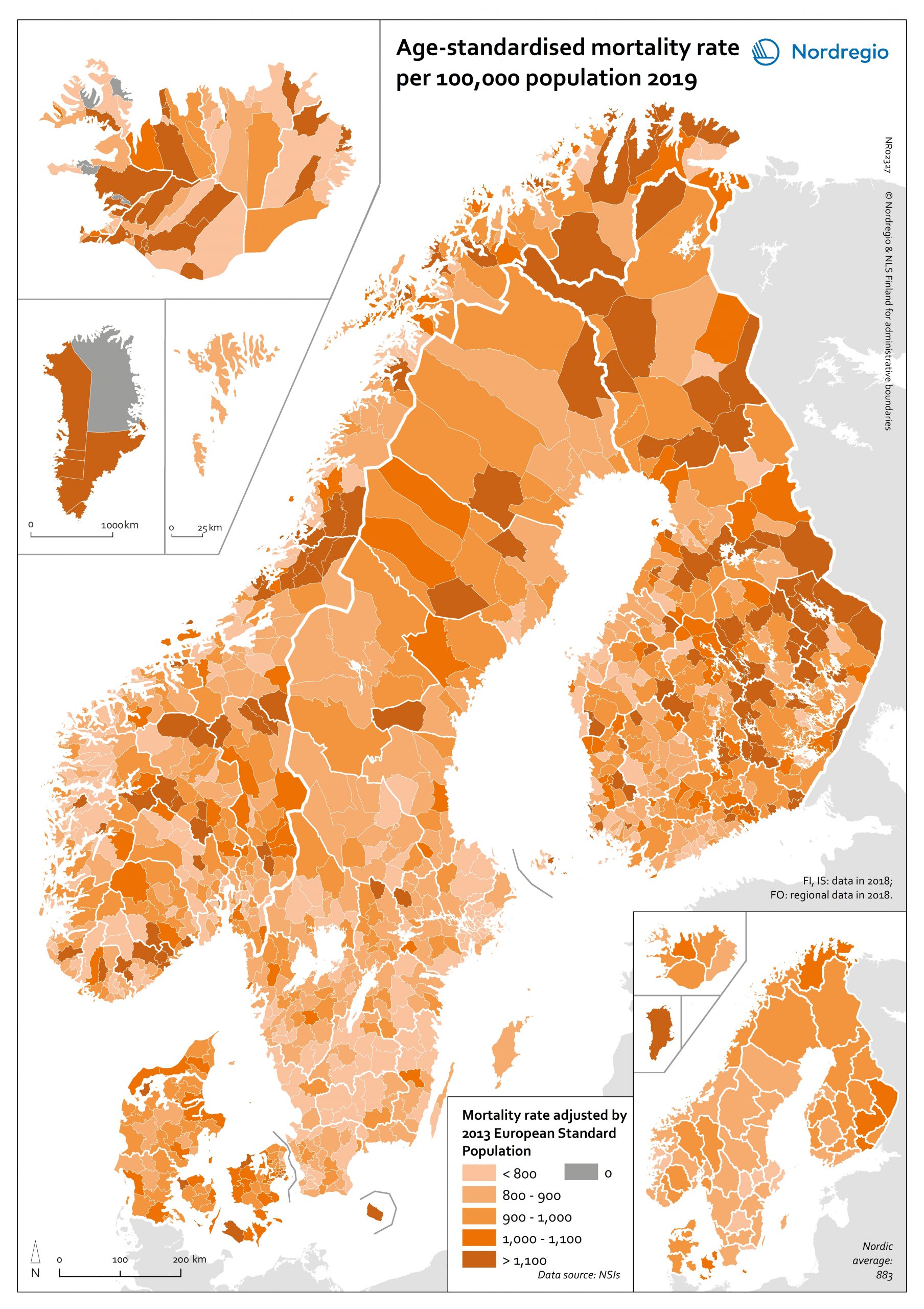

Age-standardised mortality rate 2019

The map shows mortality rate per 100,000 population in 2019 adjusted by 2013 European Standard Population. To compare the relative health status of different population groups, the population’s age distribution needs to be taken into account, because death rates for most diseases generally increase with age (Curtin & Klein, 1995). “Age-standardized mortality rates adjust for differences in the age distribution of the population by applying the observed age-specific mortality rates for each population to a standard population” (World Health Organization, 2020b). In other words, this technique allows comparison between populations with differing age profiles. The populations are thus given the same age distribution structure, so that those differences in mortality which are not due to the ageing of the population can be highlighted. At a national level, there are age-standardised mortality rates higher than the Nordic average (883.0) in Greenland (2,449.2), Denmark (988.6), and Finland (921.7). These statistics show the number of deaths per 100,000 of the population in each country, after removing variations brought about by differing age structures between the three countries. In the calculation of age-standardised mortality rates, we used the European Standard Population in 2013. It is observable that age-standardised mortality rates are lower in capital regions and large cities in all Nordic countries, suggesting a lower level of ill health in these regions. There is a high variation of mortality rates between municipalities in Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. The municipalities having the highest mortality rates tend to be economically disadvantaged, with lower levels of disposable household income and a smaller proportion of people having attained tertiary education. Since the map was created using death data for only one year, it is important to recognise that the number of deaths may vary a good deal from year-to-year in municipalities with a small population.

2021 March

- Demography

- Nordic Region