79 Maps

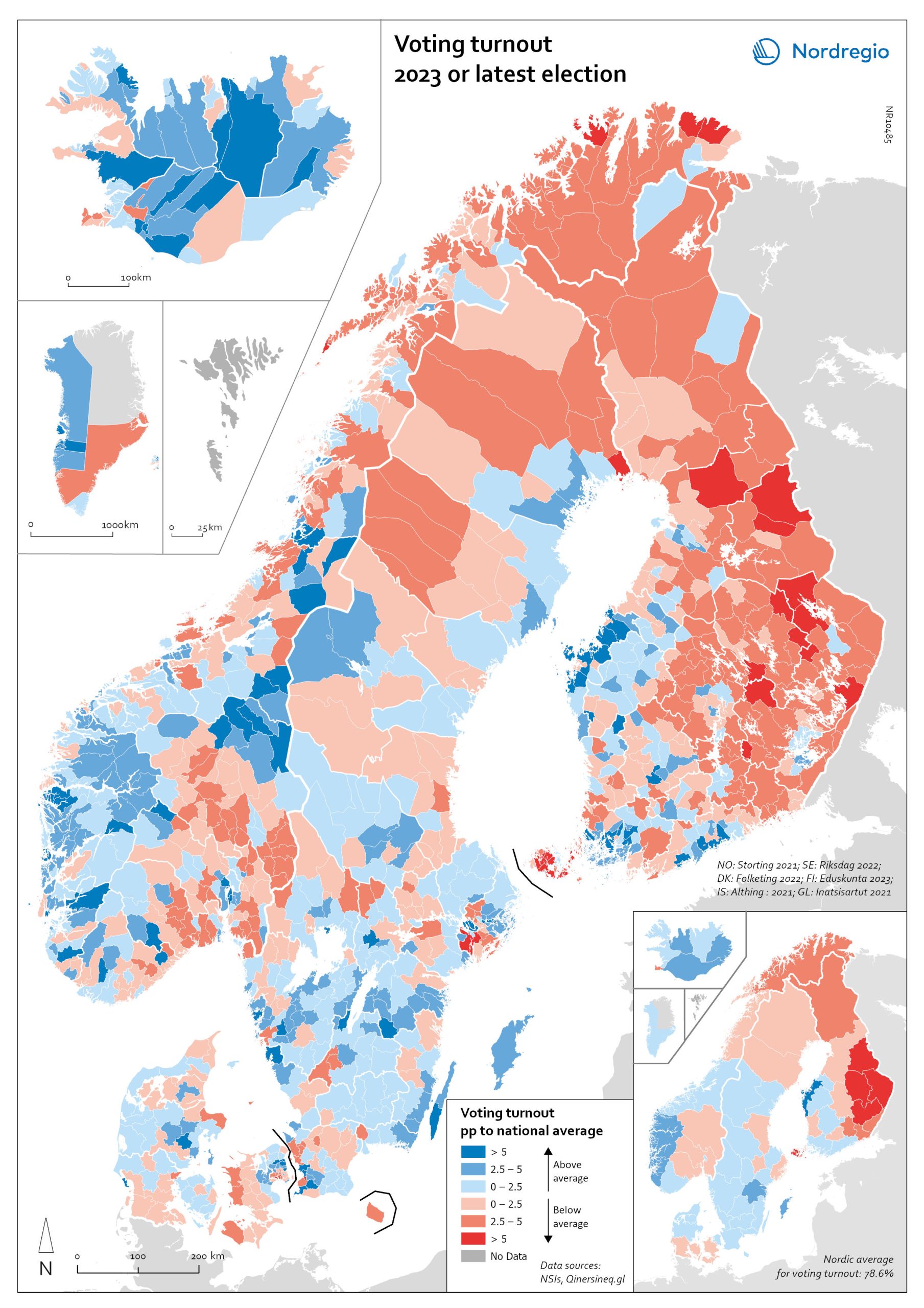

Voting turnout in national elections

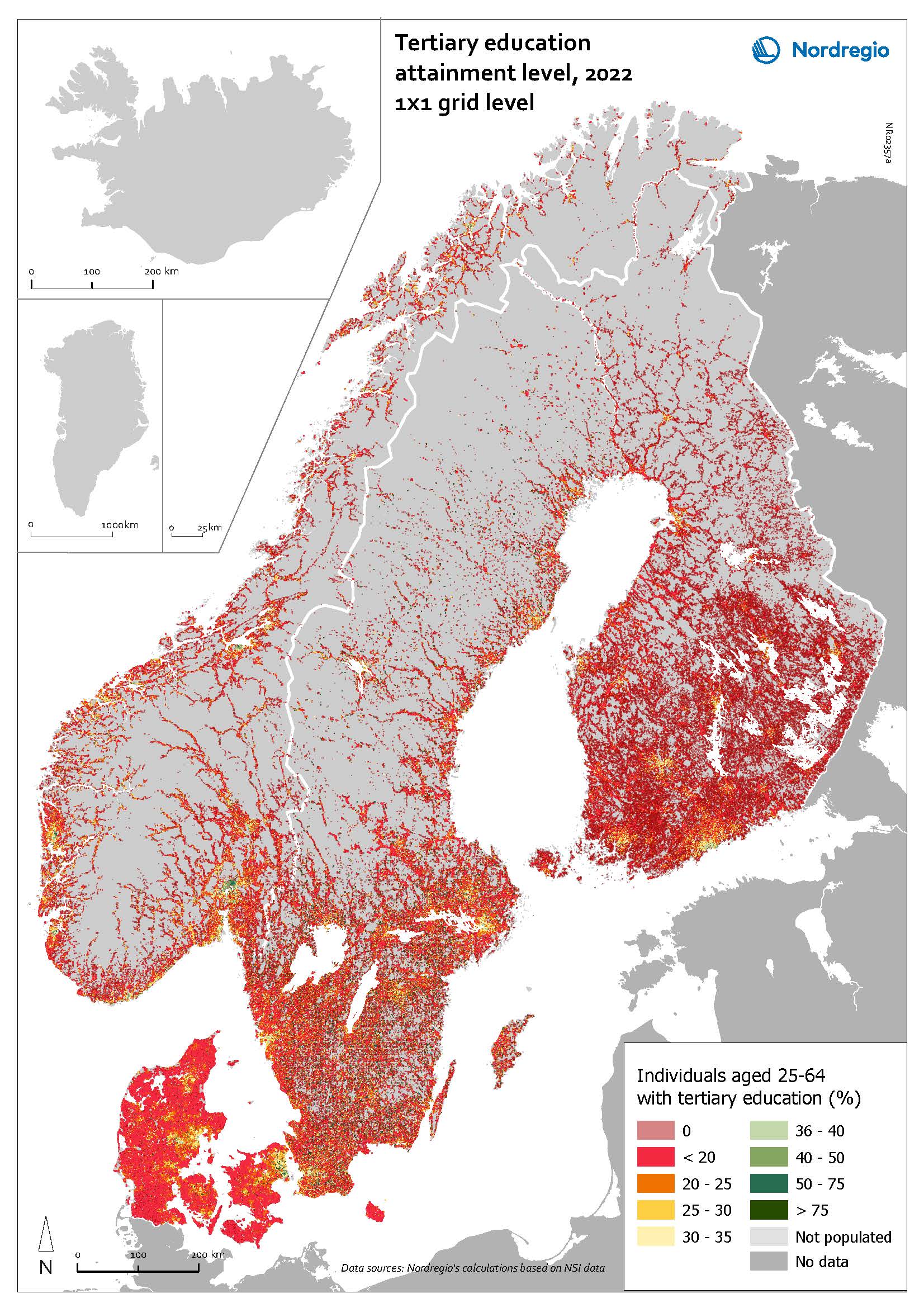

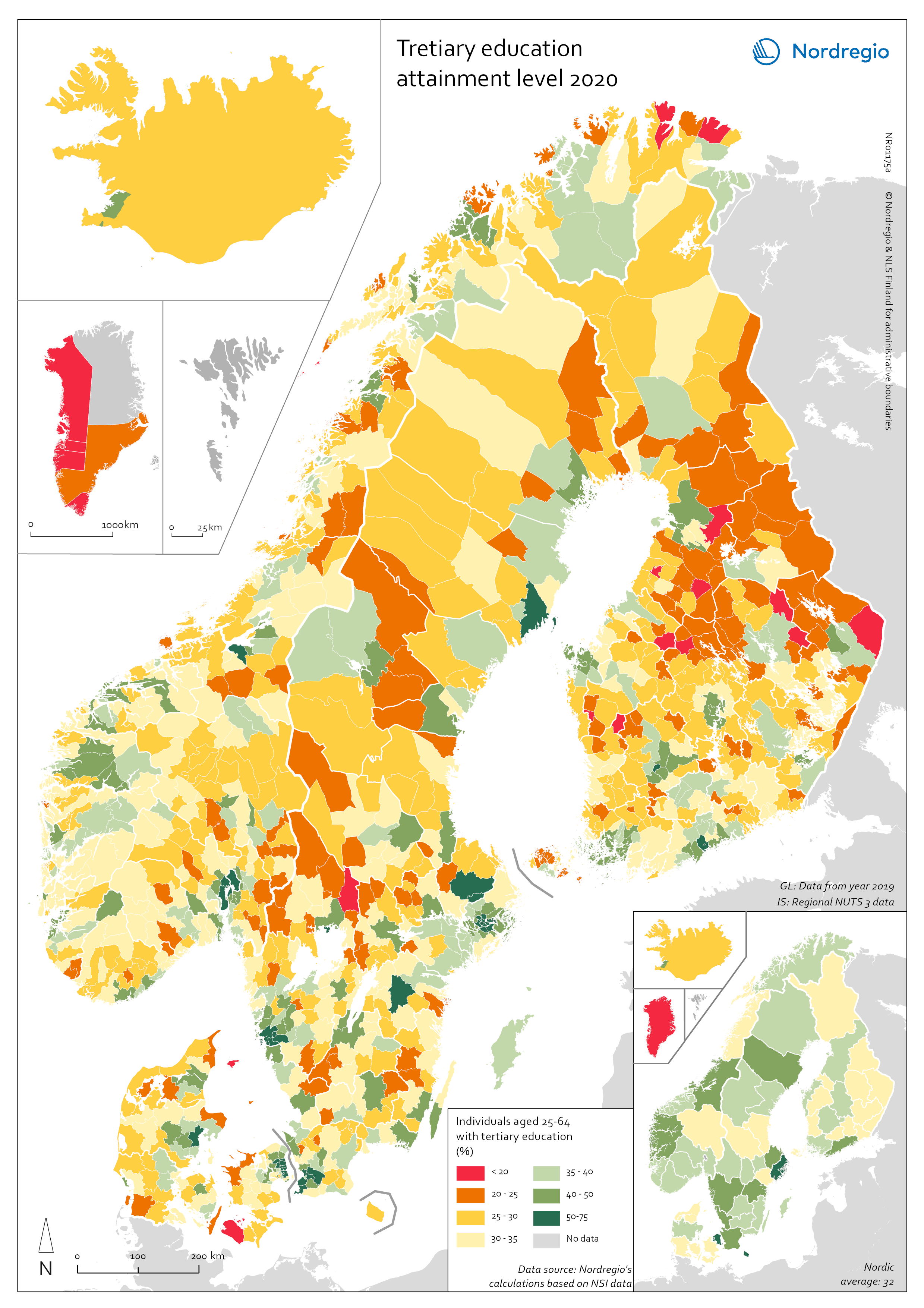

Voting turnout in 2023 (or latest national election). The map illustrates voter turnout as a percentage point relative to national averages, highlighting differences in participation levels between countries. This method removes inter-country differences in participation levels, providing a clearer view of the urban-rural divide. Lower turnout is observed in eastern Finland, northern Sweden, and the more rural parts of Denmark. In Norway, the lowest turnout occurs in the north and in municipalities outside Oslo. Nationally, the highest voter turnouts are in the Faroe Islands (88%), Sweden (84.2%), and Denmark (84.16%). Lower participation rates are found in Iceland (80.1%), Norway (77.2%), Finland (68.5%), and Greenland (65.9%).

2024 May

- Nordic Region

- Others

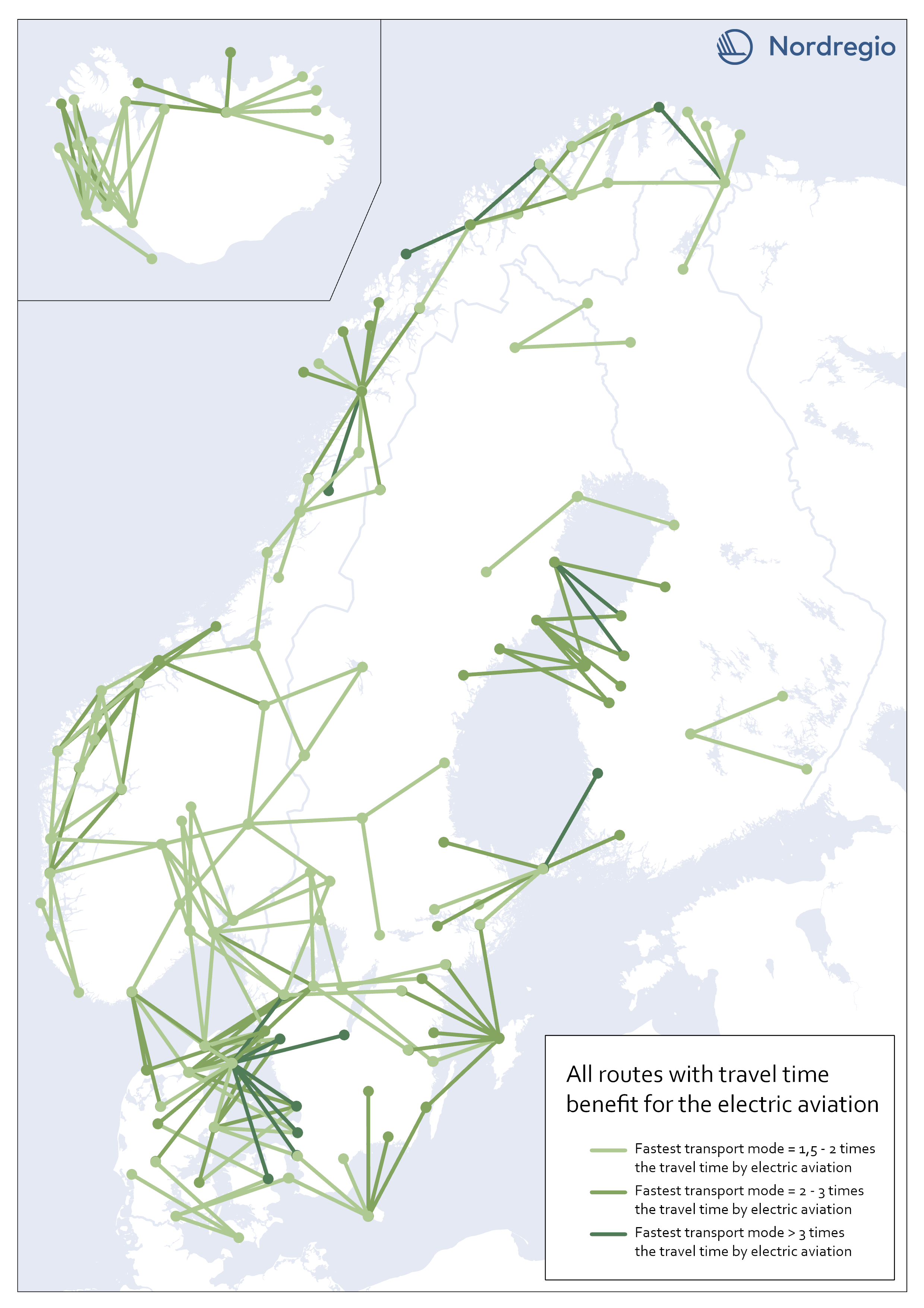

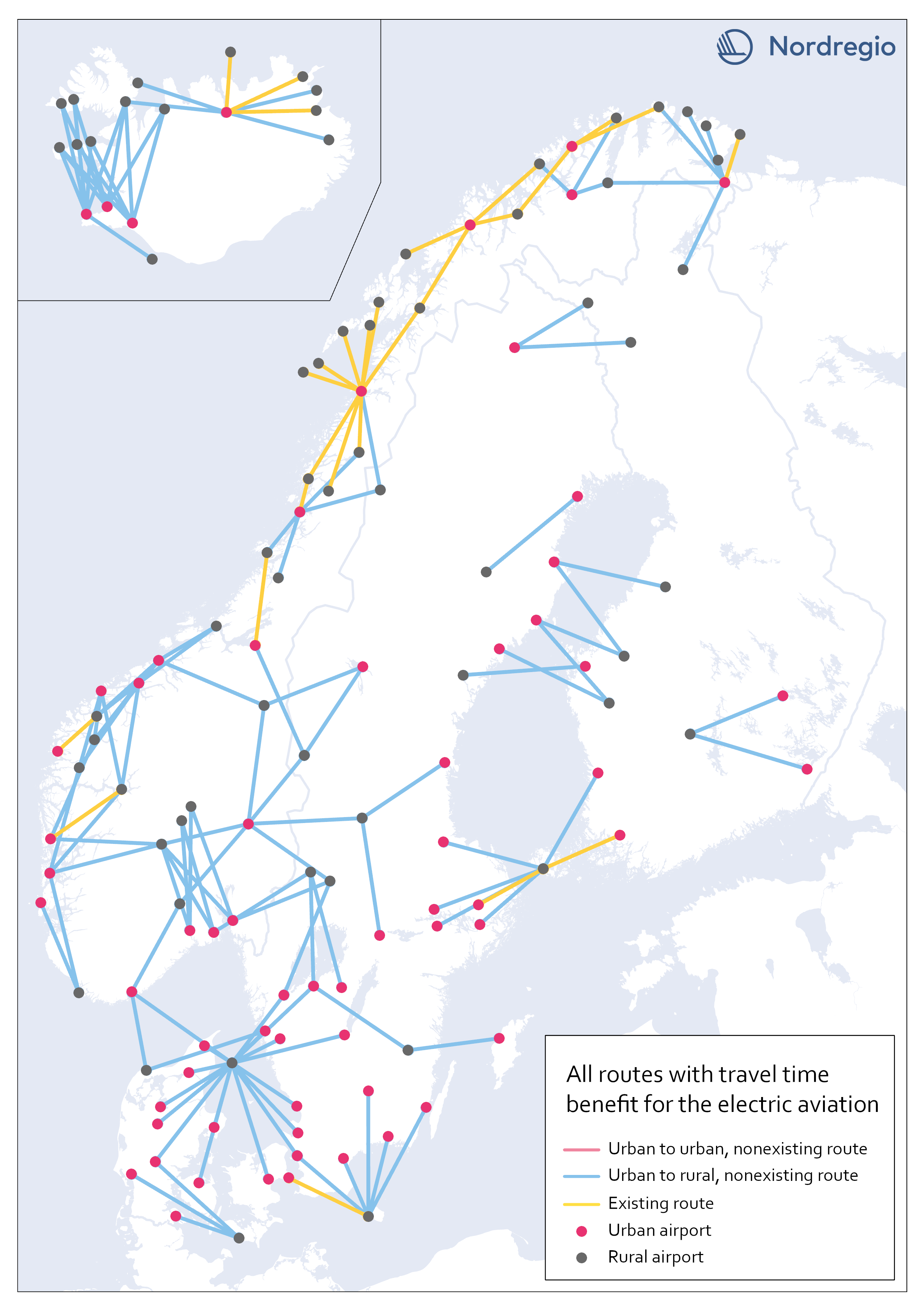

All routes with time benefit for electric aviation

The map shows all routes in our sample with significant travel time benefit for electric aviation. They are 203 in total. A route has a significant travel time benefit if the travel time for both car and public transportation exceeded 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. I.e., if one of the existing transport modes is faster or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation, electric aviation does not have the potential to improve accessibility between the two destinations, according to our analysis.

2023 February

- Nordic Region

- Transport

Electric aviation time benefits between urban and rural areas

The map shows all routes between urban and rural areas where electric aviation has significant time benefits compared to other traffic modes. Yellow lines are already served by aviation, while blue color indicates non-existent routes where electric flight would reduce the travel time between destinations. Our motivation for focusing on urban-rural routes was based on the assumption that electric aviation can increase the access for rural areas to public facilities and job opportunities, as well as the possibility of connecting remote areas with national and international transport systems. The result, though, can only be understood in terms of travel time benefits between the areas, and thus reveals little about accessibility to mentioned opportunities. The following are examples of themes to be investigated further within the main project. Identify regional hubs Among others, the project FAIR (2022) has addressed the need to update the flight system to a more flexible aviation network, that meet travelers’ needs with smart mobility. This can be done by identifying demands and establishing regional hubs for electric aviation, which can serve remote and regional areas. The potential of Hamar and Bodö in Norway as regional hubs should be studied more closely.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

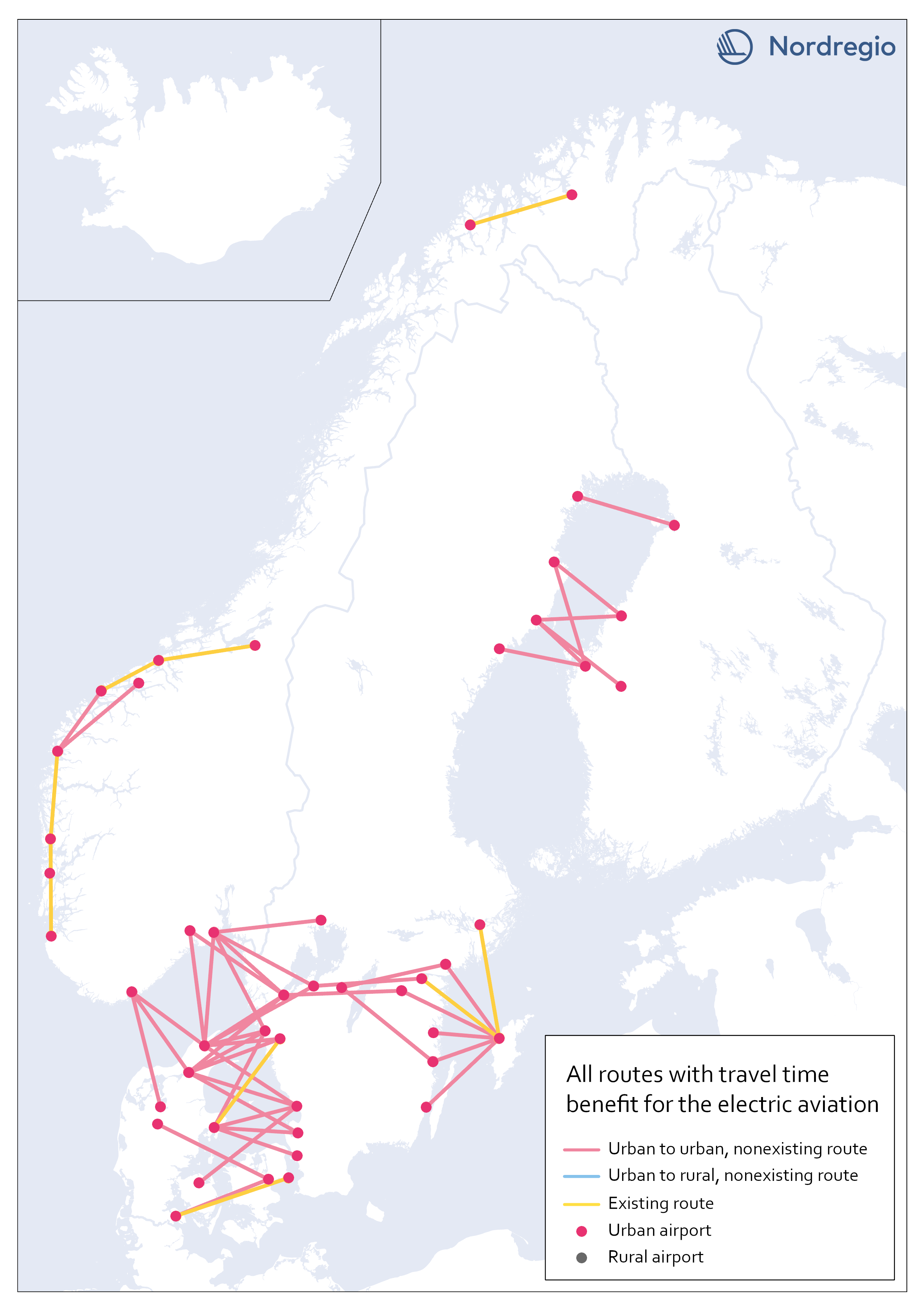

Electric aviation time benefits between urban areas separated by water

The map shows all routes between urban areas separated by water, and where electric aviation has significant time benefits compared to the fastest traffic mode. Yellow lines are already served by aviation, while red color indicates non-existent routes where electric flight would reduce the travel time between destinations. The result is in line with our assumptions, that there is a lack of fast connections between potential labor markets in urban areas, which are geographically close but separated by open water.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

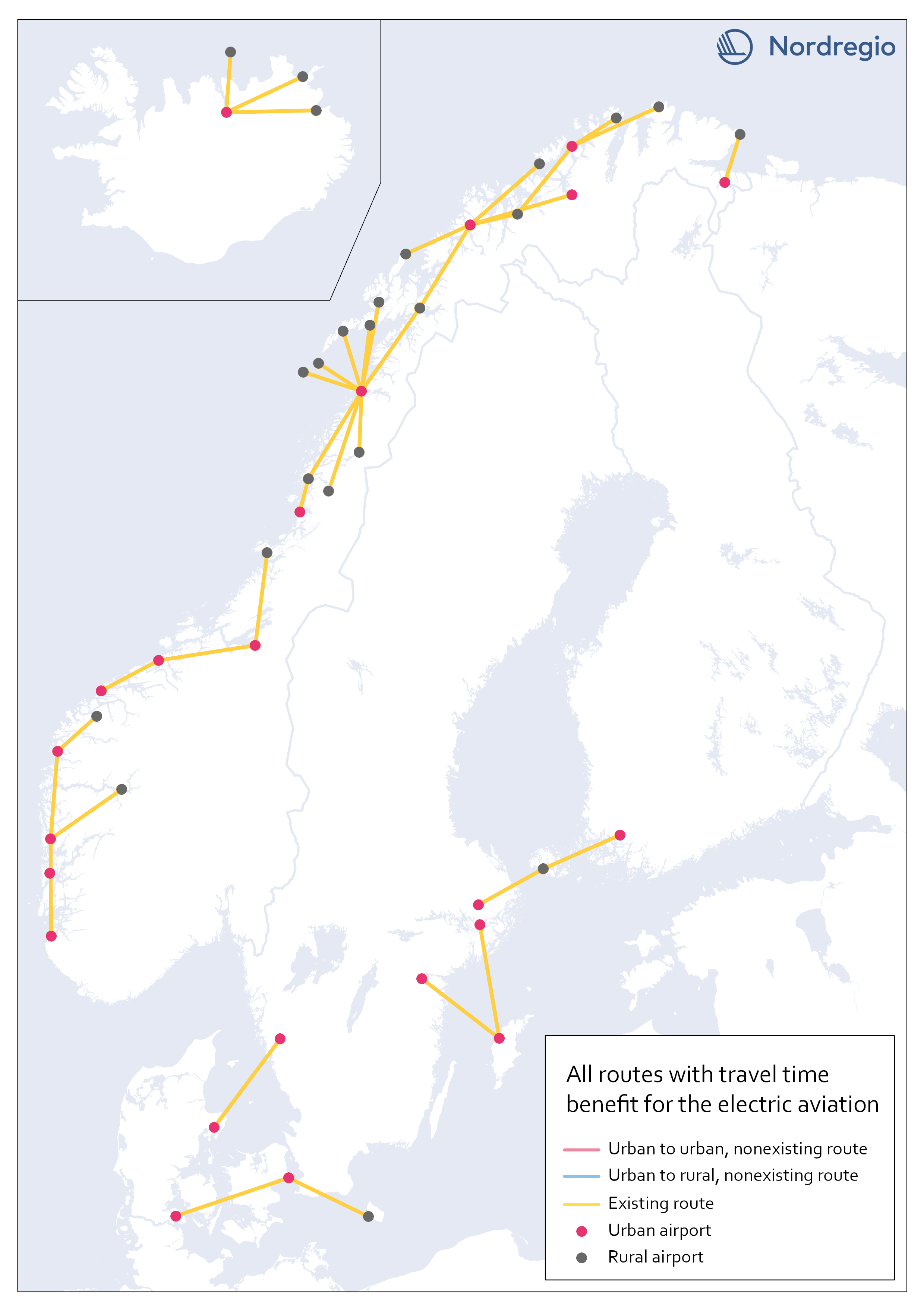

Existing routes with time benefit for electric aviation

The map visualizes all routes with significant travel time benefit, which are already served with commercial flights. Information on existing routes has been obtained from the report Nordic Sustainable Aviation (Ydersbond et al, 2020) and applies to the year 2019. Since then, routes may have been added or removed, which is important to bear in mind in future investigations. However, choosing a later year risk giving equally misleading results, as flights decreased drastically during the pandemic. Statistics for 2019 provide a picture of the demand that existed before the pandemic, which is the latest stable levels that can be obtained. Whether air traffic will ever return to the same levels as before the pandemic is too early to say. The majority of routes are found in Norway, along the coastline, which confirms earlier knowledge that Norway has a more extensive and coherent aviation network than the rest of the Nordic region.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

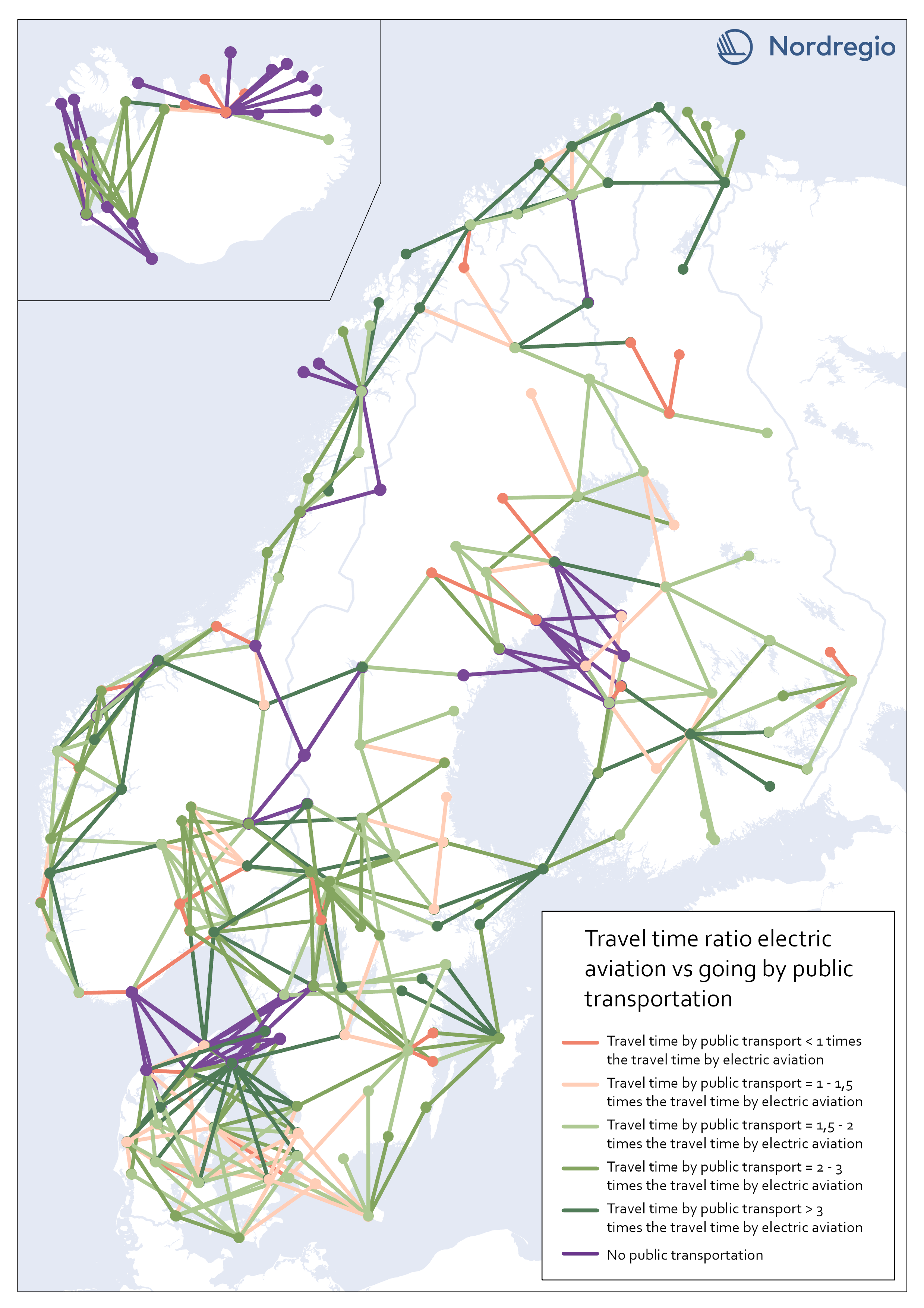

Travel time ratio – electric aviation vs public transportation

This map shows the travel time calculations for electric aviation versus travelling by public transportation. Routes represented by any nuance of green, are routes with significant travel time benefits for electric aviation in comparison with public transportation. The darker the nuance of green, the larger time benefit for electric aviation. The beige color represents routes where the travel time for public transportation is the same or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. The red color represents routes where public transportation is faster than electric aviation. Purple lines represent routes where no public transportation is available. These were also routes where we could see significant time benefits for electric aviation. The number of changes when commuting with public transport may have a negative impact on perceived accessibility. In this accessibility analysis, however, we stay with the same criteria for public transport as for travel by car. For future research, the number of changes when commuting by public transport could be considered in the comparison.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

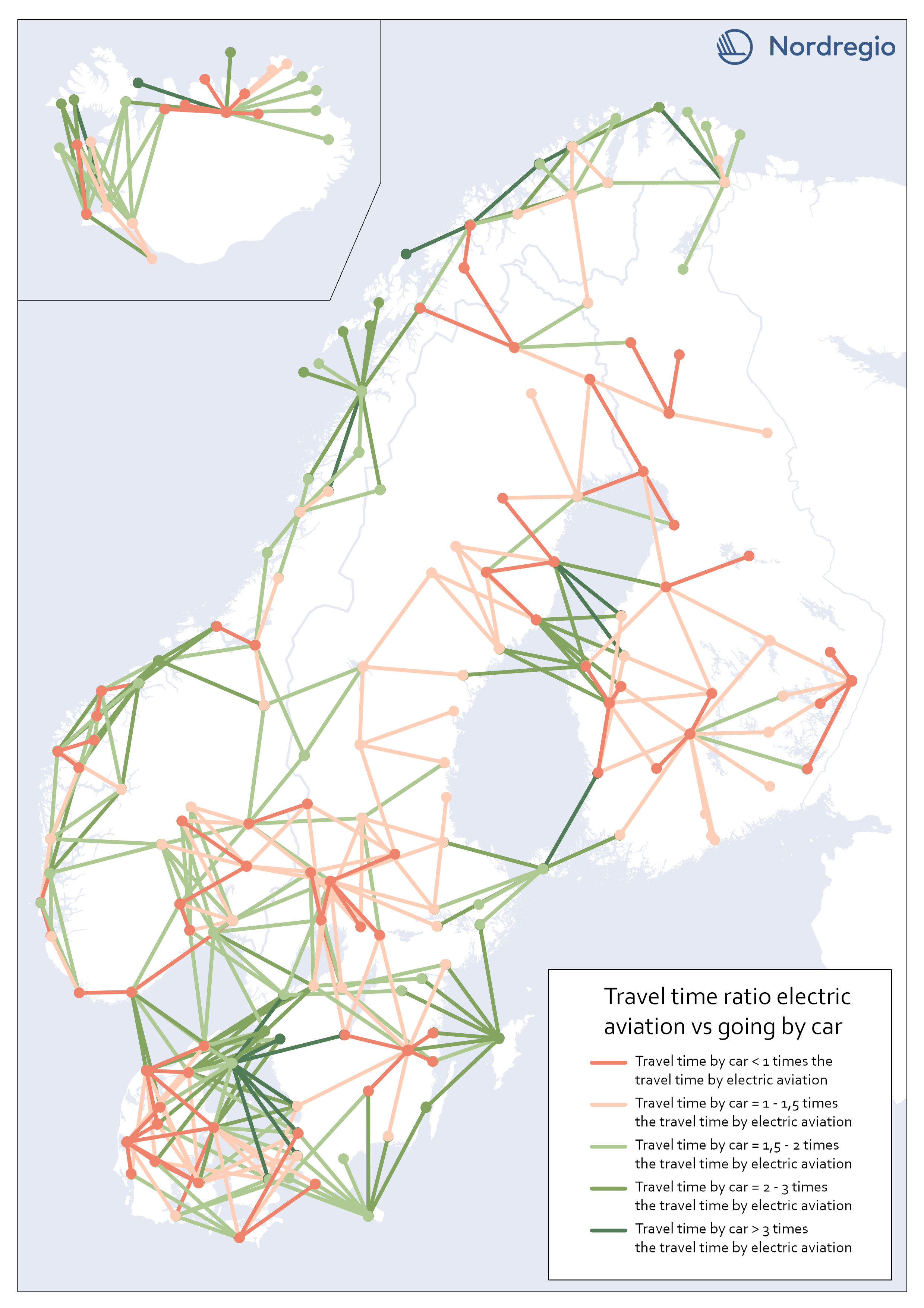

Travel time ratio – electric aviation vs car

This map shows the travel time calculations for electric aviation versus traveling by car. Routes represented by any nuance of green, are routes with significant travel time benefits for electric aviation in comparison with car. The darker the nuance of green, the larger time benefit for electric aviation. The beige color represents routes where the travel time for car is the same or up to 1,5 times the travel time for electric aviation. The red color represents routes where car is faster than electric aviation.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

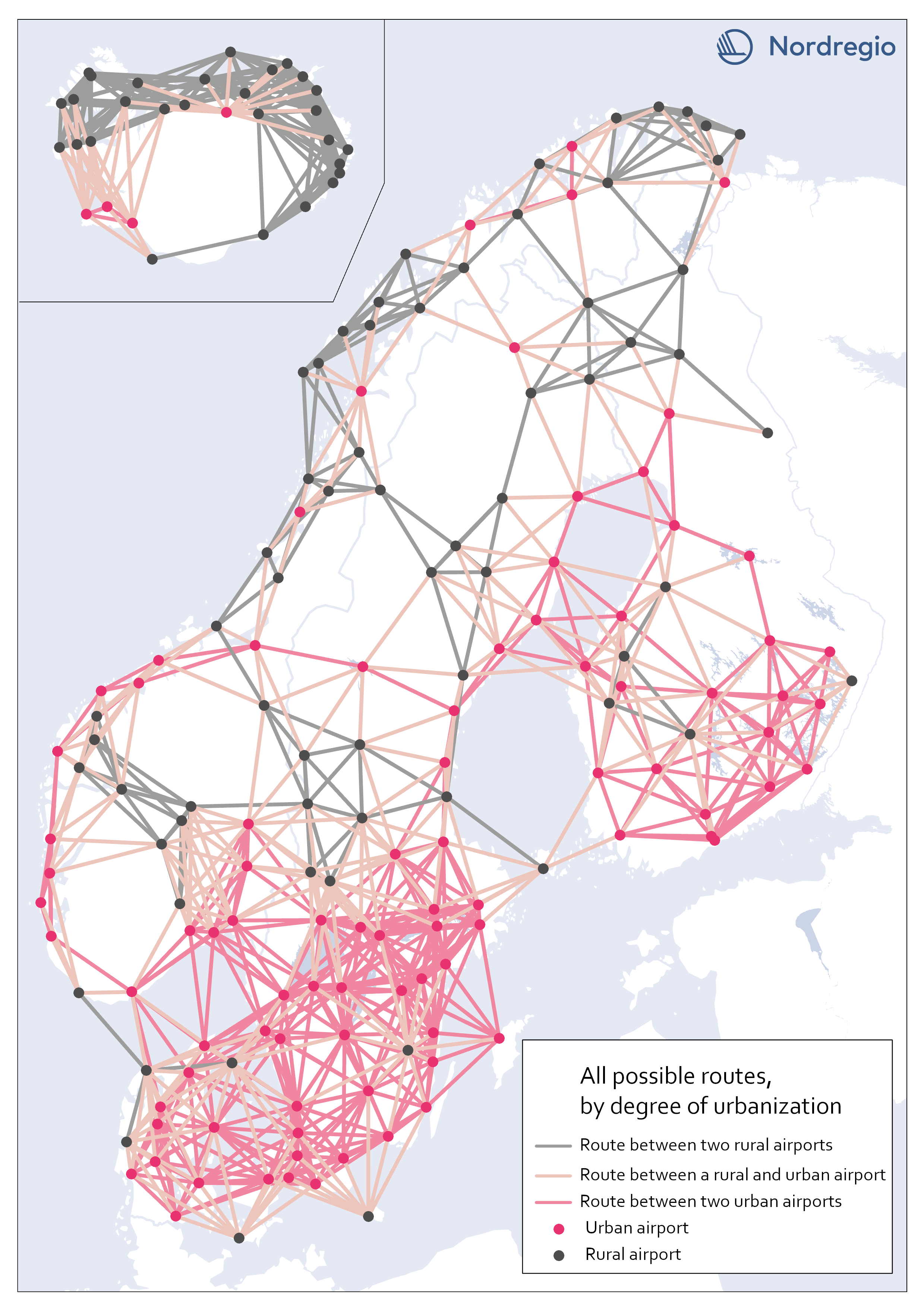

All possible electric aviation routes by a degree of urbanisation

The map shows all routes with a maximum distance of 200 km divided into three categories, based on the airports’ degree of urbanization: Routes between two rural airports, routes between one rural and one urban airport and routes between two urban airports. The classification is based on the new urban-rural typology. We restricted the analysis to routes between rural and urban areas as well as routes between urban areas that are separated by water. Those are 426 in total. We based our criteria on the assumption that accessibility gains to public services and job clusters can be made for rural areas, if better connected to areas with a high degree of urbanization. Because of possible potential to link labor markets between urban areas on opposite sides of water urban to urban areas that cross water are also included. This is based on previous research which has shown the potential for electric aviation to connect important labor markets which are separated by water, particularly in the Kvarken area (Fair, 2022). Our choice of selection criteria means that we intentionally ignore routes where electric aviation may have a potential to reduce travel times significantly. There might also be other important reasons for the implementation of electric aviation between the excluded routes. Between rural areas, for example, tourism or establishing a comprehensive transport system in the Nordic region, constitute reasons for implementing electric aviation. Regarding routes between urban areas over mainland, the inclusion of more routes with the same rationale as above – that significant time travel benefits could be gained between labor markets with electric aviation (for example between two urban areas in mountainous regions where travel times can be long) – can be motivated. Some of those routes can be important to investigate at a later stage but are outside the…

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

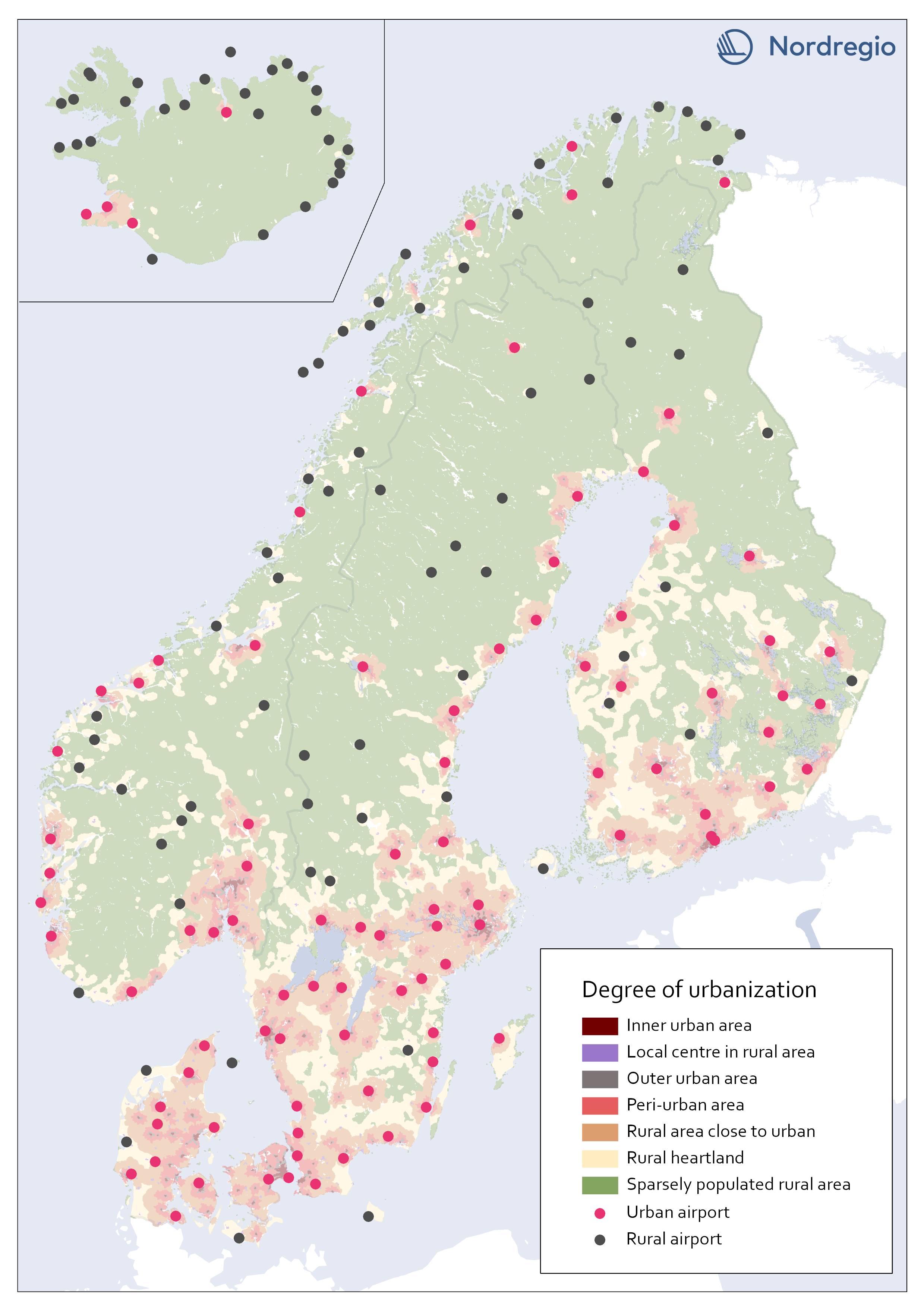

All airports in the Nordic region by a degree of urbanisation

This map classifies all airports by a degree of urbanisation. The classification is based on the new urban-rural typology. We classified all airports localized within any of the top five urbanization classes (Inner urban area, Local center in rural area, Outer urban area, peri-urban area, or Rural area close to close to urban) as Urban. All other airports, localized within the bottom two classes (Rural heartland or Sparsely populated rural area) were classified as Rural. No adjustments were made based on the proximity of the airports to urban areas. During the process we considered adjustments in the categorization based on the airports’ potential catchment area from a close urban area. For example, one can assume that Gällivare Lappland airport in the north of Sweden, has its main catchment area from Gällivare which is classified as a local center in rural area (i.e. Urban). The airport, though, is localized within the category Rural heartland. Yet, we decided to let the typology determine to which category each airport belong.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

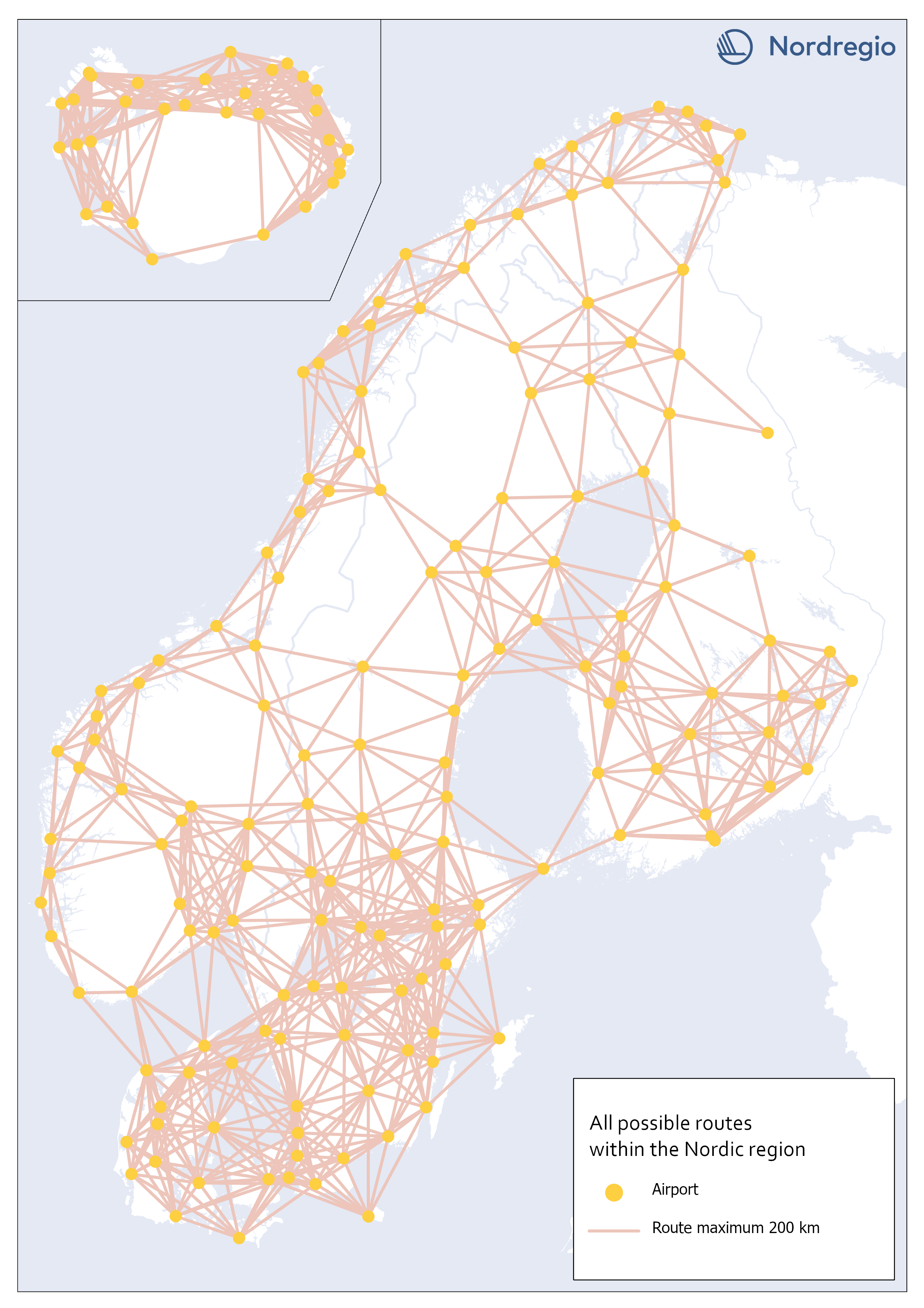

All possible electric aviation routes, max 200km, within the Nordic region

This map shows all possible electric aviation routes of a maximum distance of 200 kilometres within the Nordic region. First generation electric aviation will have a limited range due to battery capacity. According to the report Nordic Sustainable Aviation, routes up to 400 kilometers constitute an initial market for electric airplanes in the Nordic region. However, also shorter distance routes under 200 km, where cruise speed is less important and in sparsely populated regions where passenger volumes are very small, will be the focus (Ydersbond et al, 2020). The first generation of aircrafts that rely solely on electric power have a defined maximum range of 200 km (Heart Areospace, 2022). For this accessibility study, we only included routes of a maximum distance of 200 kilometers. This selection gave us 1001 possible routes in total.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

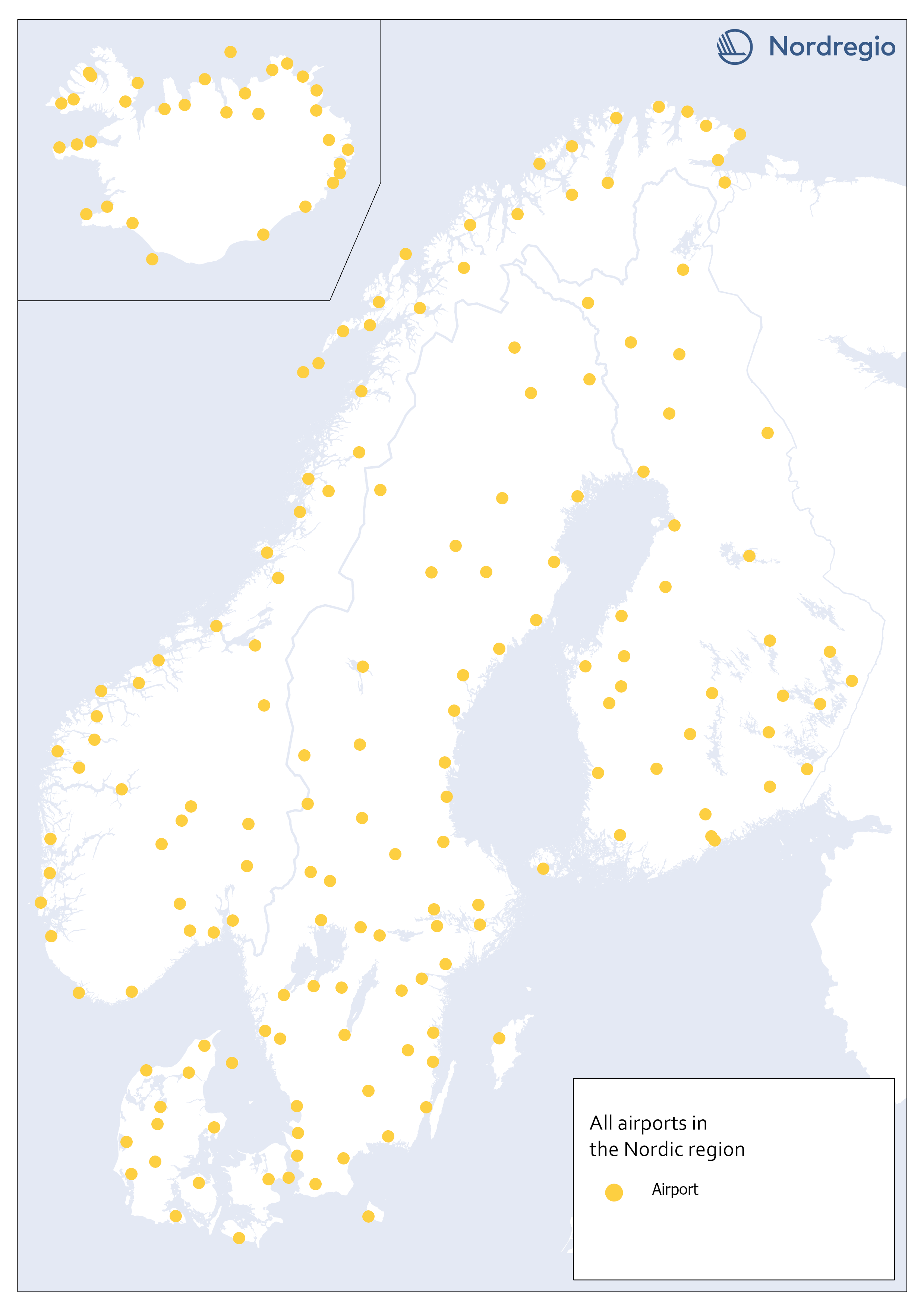

All airports in the Nordic region

This map shows all airports within the geographical scope which may be operated with commercial flight. To limit our selection of airports, we used a combination of two official airport code systems: IATA (International Air Transport Association) and ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization). IATA-codes specify the airport as a part of a commercial flight route. However, the IATA system, is not solely limited to airports. Other locations, such as bus or ferry stations can also apply for an IATA location code, as long it is included in an airline travel chain. The ICAO-code, on the other hand, indicates that the location is an airport, but not necessarily for commercial flights In order to obtain a selection of airports that met our criteria, an airport was included only if it had both an IATA-code and an ICAO-code. Three different sources are used: 1) Swedavia (lists all airports in the Nordics that Swedavia traffics today). This is our main source, but it does not include all existing airports in the Nordic countries. Therefore, we also use two other sources: 2) Avcodes: Airport code database, from which other airports, that are not served by Swedavia, are obtained. 3) Wikipedia. Finally, the listed airports are checked against Wikipedia, to verify if any airports have been missed through the other sources. This selection gave us 186 airports in total.

2023 January

- Nordic Region

- Transport

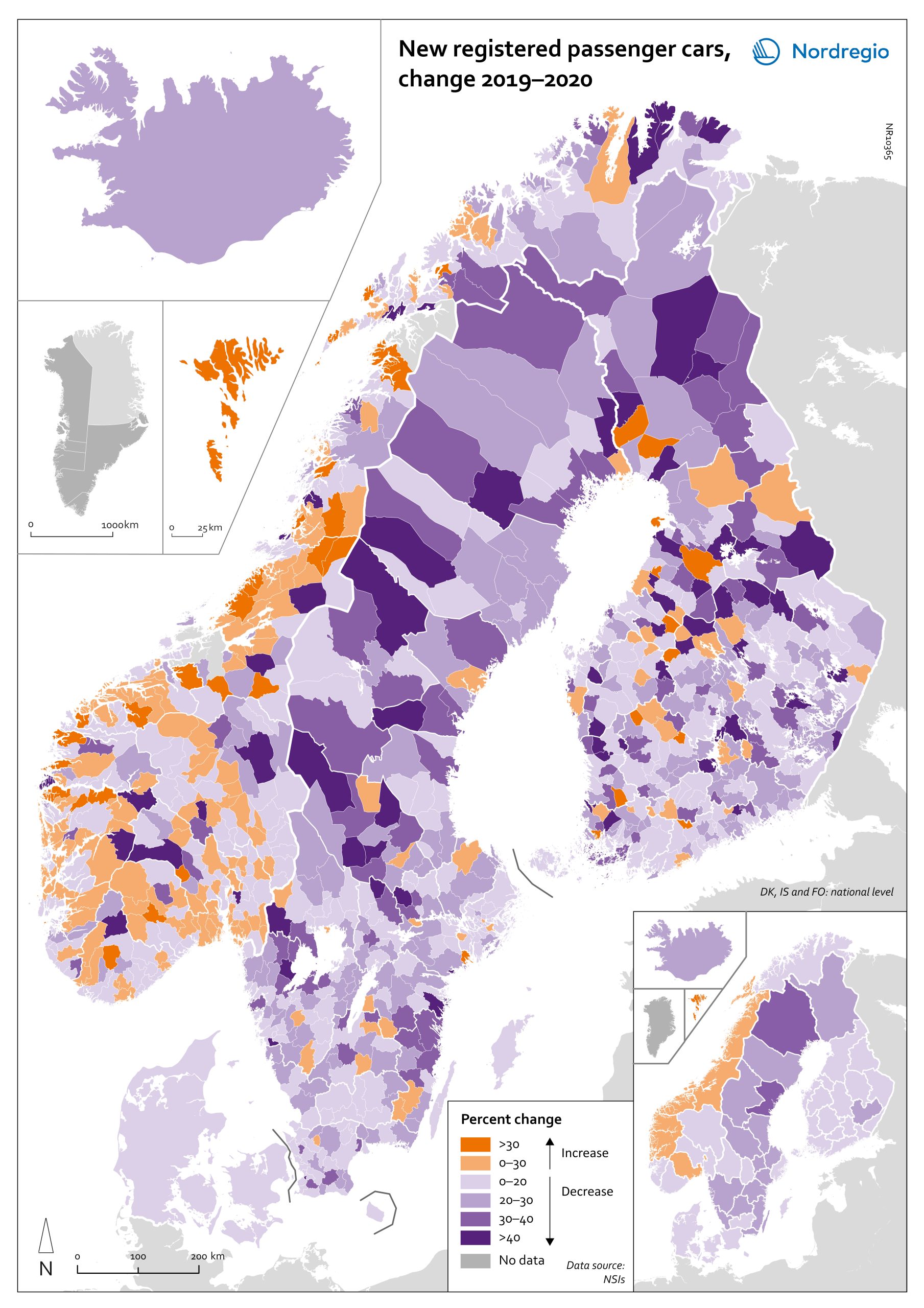

Change in new registered cars 2019-2020

The map shows the change in new registered passenger cars from 2019 to 2020. In most countries, the number of car registrations fell in 2020 compared to 2019. On a global scale, it is estimated that sales of motor vehicles fell by 14%. In the EU, passenger car registrations during the first three quarters of 2020 dropped by 28.8%. The recovery of consumption during Q4 2020 brought the total contraction for the year down to 23.7%, or 3 million fewer cars sold than in 2019. In the Nordic countries, consumer behaviour was consistent overall with the EU and the rest of the world. However, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Åland, and Denmark recorded falls of 22%–11% – a far more severe decline than Norway, where the market only fell by 2.0%. The Faroe Islands was the only Nordic country to record more car registrations, up 15.8% in 2020 compared to 2019. In Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, there were differences in car registrations in different parts of the country. In Sweden and Finland, the position was more or less the same in the whole of the country, with only a few municipalities sticking out. In Finland and Sweden, net increases in car registrations were concentrated in rural areas, while in major urban areas, such as Uusimaa-Nyland in Finland and Västra Götaland and Stockholm in Sweden, car sales fell between 10%–22%. Net increases in Norway were recorded in many municipalities throughout the whole country in 2020 compared to 2019.

2022 March

- Economy

- Nordic Region

- Transport

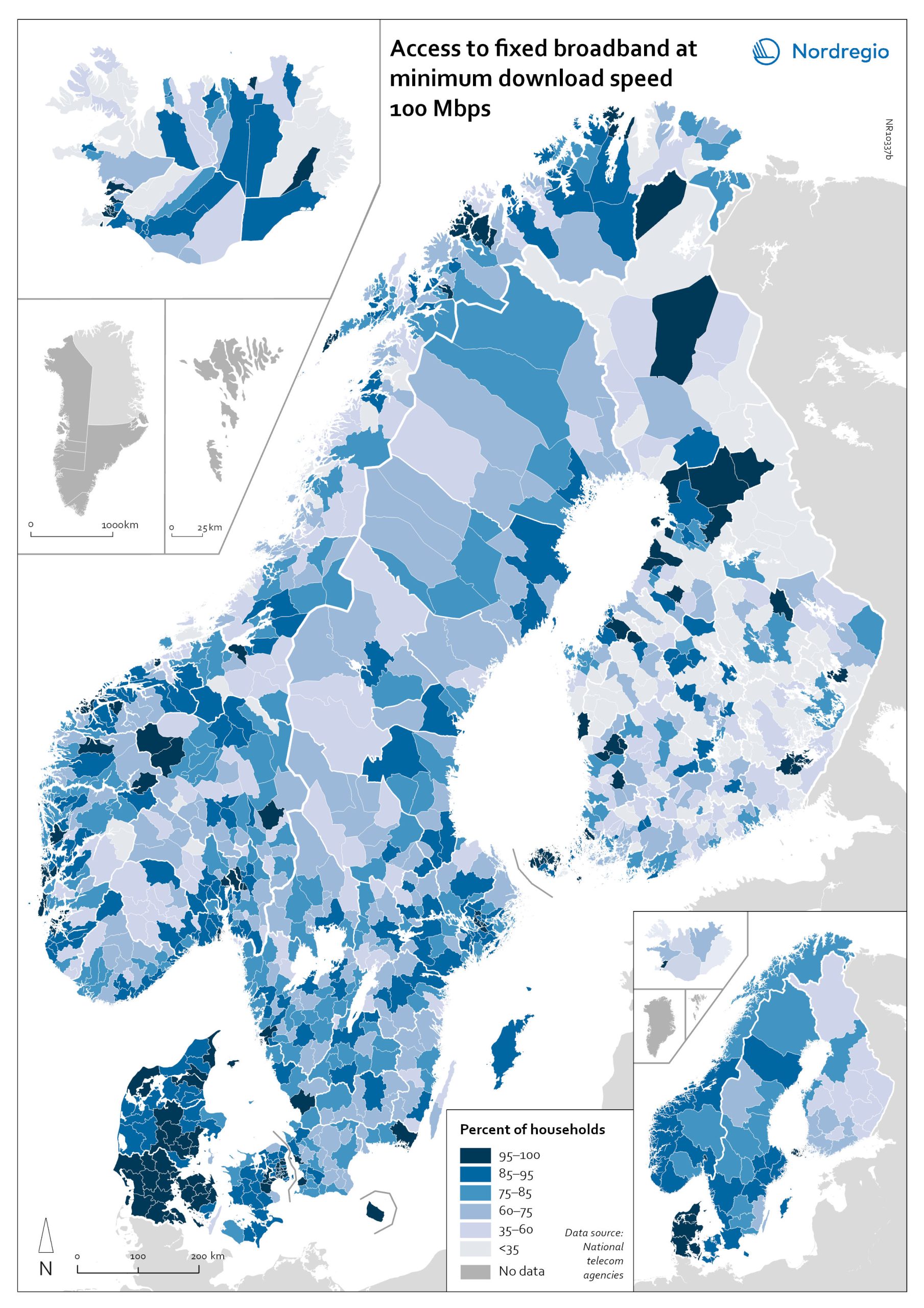

Access to fixed broadband at minimum download speed 100 Mpbs

The map shows the proportion of households that had access to fixed-line broadband with download speeds >100 Mbps (superfast broadband) at the municipal level, with darker colours indicating higher coverage. Overall, Denmark has the highest levels of connectivity, with 92% of municipalities providing superfast broadband to at least 85% of households. In over half (59%) of all Danish municipalities, almost all (>95%) of households have access to this connection speed. The lowest levels of connectivity are found in Finland. This is particularly evident in rural municipalities where, on average, less than half of households (48%) have access to superfast broadband. Connectivity levels are also rather low in some parts of Iceland, for example, the Westfjords and several municipalities in the east. Households in urban municipalities are still more likely to have access to superfast broadband than households in rural or intermediate municipalities, but the gap appears to be closing in most. This is most evident in Norway, where the average household coverage for rural municipalities increased by 31% between 2018 and 2020. By comparison, average household coverage for urban municipalities in Norway increased by only 0.7%. In the archipelago (Åland Islands, Stockholm and Helsinki), general broadband connectivity is good; however, some islands with many second homes still have poor coverage.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Others

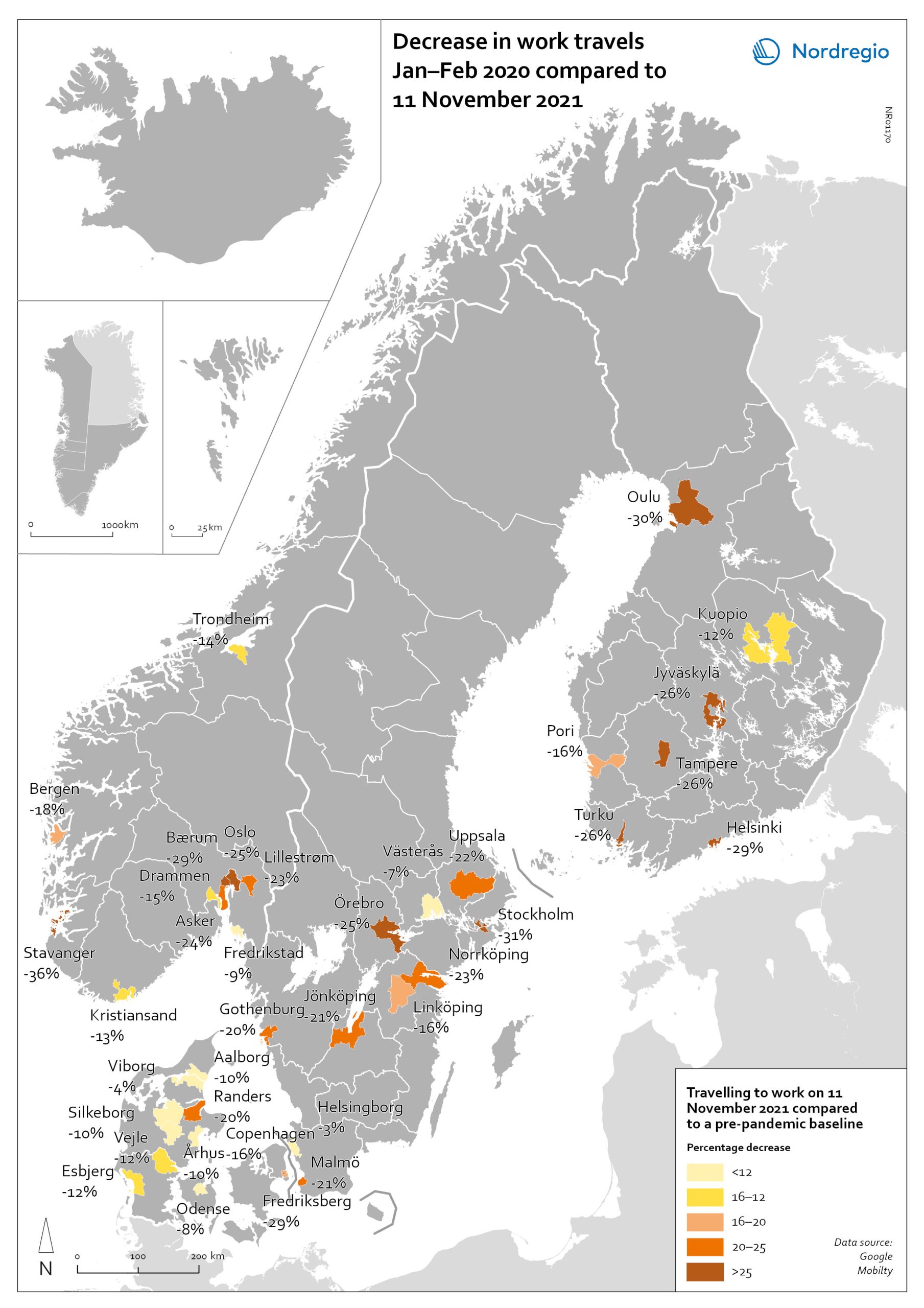

Change in work travels Jan-Feb 2020 compared to Nov 2021

The map shows changes in number of people travelling to work in the Nordic municipalities with the biggest populations comparing November 2021 to a pre-pandemic baseline. The map compares the average number of people who travelled to work on a weekday in January and February 2020 with the number of people who travelled to work on 11 November 2021 in the ten largest cities of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The date was selected as the reference date as it is considered to be a relatively typical Thursday. It also represents a point when few movement restrictions were in place in the Nordic countries. As can be seen from the map, all of the municipalities highlighted recorded a fall in work-related travel on 11 November compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. It was biggest in Stavanger (-36%), followed by Stockholm (-31%), Oulu (-30%), Bærum (adjacent to Oslo) (-29%), Frederiksberg (adjacent to Copenhagen) (-29%) and Helsinki (-29%). In general, the decrease was highest around the capital regions and larger cities, but there were exceptions, for example, Jyväskylä (-26%), Örebro (-25%), Jönköping (-21%), and Randers (-20%). Several large municipalities also stood out because their patterns did not change so much, for example, Helsingborg (-3%) and Västerås (-7%) in Sweden; Viborg (-3%) and Odense (-8%) in Denmark.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

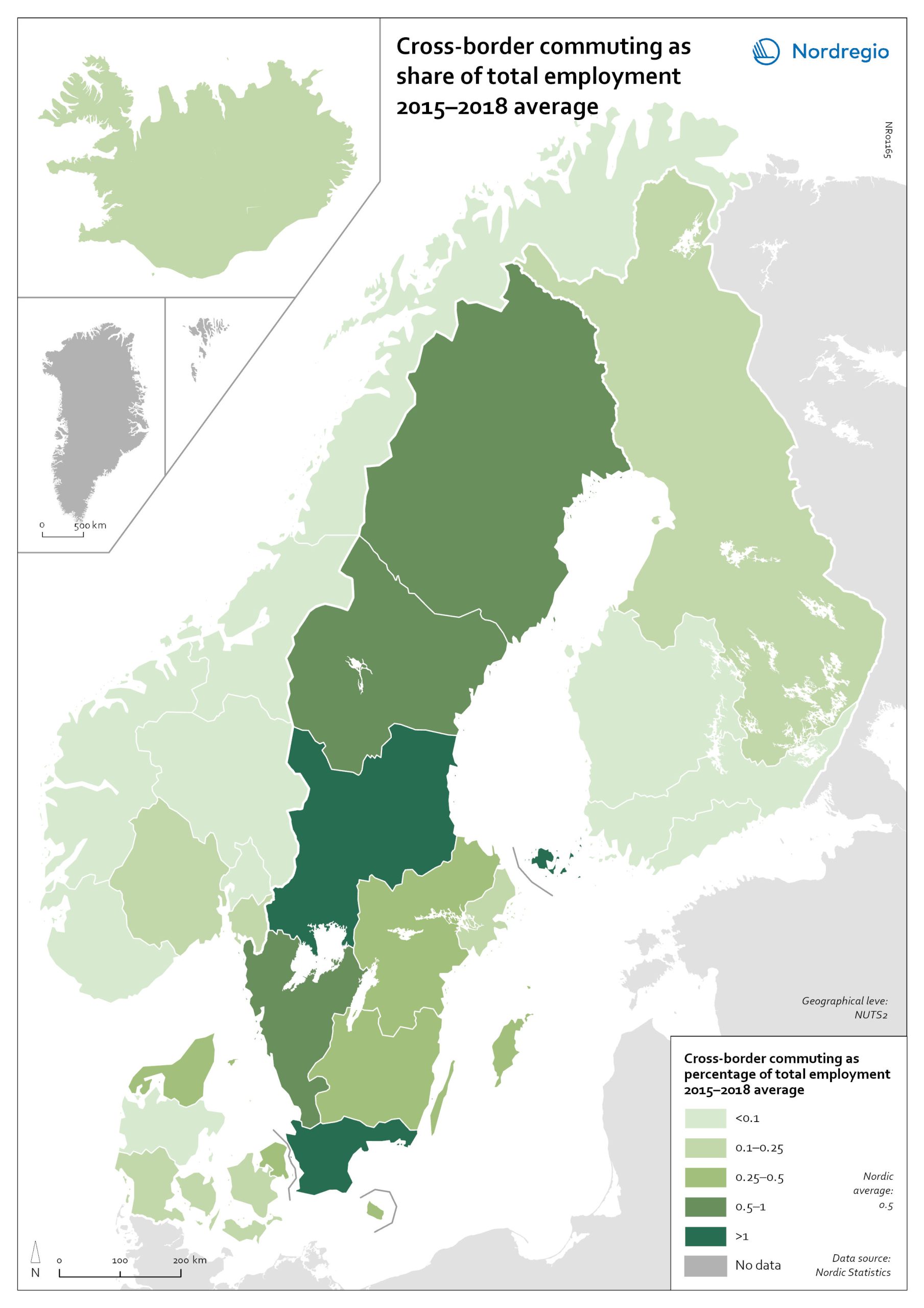

Cross-border commuting as share of employment

The map illustrates the average share of employees who commuted to another Nordic country between between 2015 and 2018 in Nordic regions (NUTS 2). Between 2015 and 2018, an average of approximately 49,000 people held a job in a Nordic country in which they were not residents. This indicates that, on average, 0.5% of the Nordic working-age population commuted to a job in another Nordic country. This is below the EU27 average of 1%, with the highest numbers found in Slovakia (5.1%), Luxembourg (2.8%) and Estonia (2.6%). Some of these people cross borders daily. Others work in another country by means of remote working combined with occasional commuting across borders. Within the Nordic Region, the largest cross-border commuter flows are in the southernmost parts of Sweden, regions in the middle of Sweden and in Åland, where more than 1% of the working population commutes to another Nordic country. However, there may be individual municipalities where cross-border commuting is substantially higher. For example, the employment rate in Årjäng Municipality, Sweden, increases by 15 percentage points when cross-border commuting is taken into account. These municipalities are not reflected on NUTS 2 level when averages are calculated. In terms of absolute numbers in 2015, the highest numbers of commuters were from Sweden: Sydsverige (16,543), Västsverige (7,899) and Norra Mellansverige (6,890). The highest number of commuters from a non-Swedish region were from Denmark’s Hovedstaden (2,583). Due to legislative barriers regarding the exchange of statistical data on cross-border commuting between the Nordic countries, more recent data is not available.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

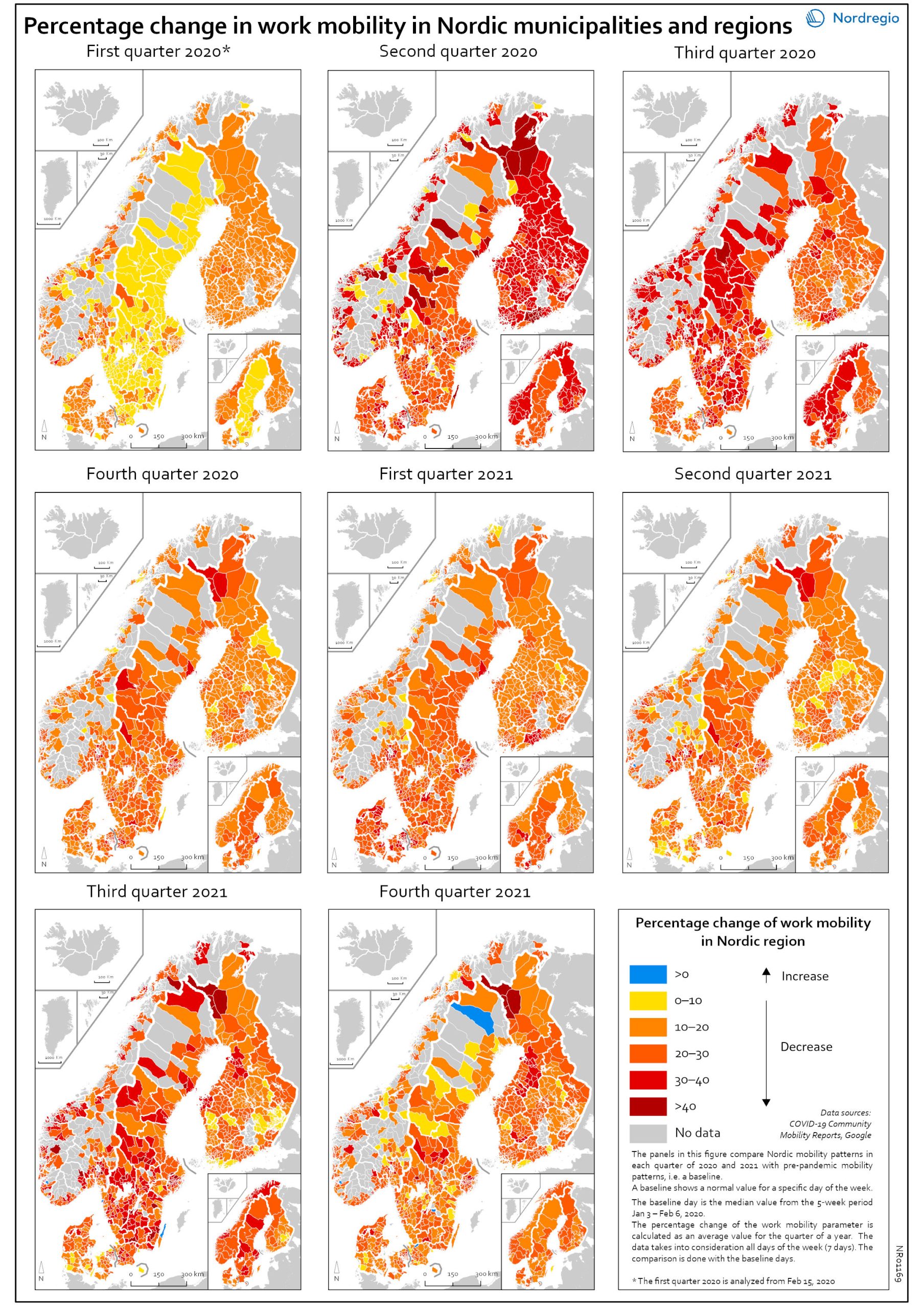

Work mobility per municipality and region by quarter

The map shows the percentage change for work mobility in Nordic regions and municipalities compared to a pre-pandemic baseline. The maps compare Nordic mobility patterns in each quarter of 2020 and 2021 with a pre-pandemic baseline. Based on Google data, the panels illustrate the impact of national restrictions and how those restrictions hampered work mobility. As the restrictions were both national and regional in nature, some regions and municipalities were more affected than others. The darker areas in the map show that work mobility decreased the most Q2 and Q3 2020 and in Q3 2021. The panels also show that mobility decreased later in Sweden than in the other Nordic countries. However, the decrease in Q3 in both 2020 and 2021 may partly be explained by the summer vacation months, when work mobility tends to decrease anyway. In Q4 2021, the overall situation seems to improve, although the pattern is mixed. In a few municipalities the situation is almost back to pre-pandemic baseline while in most municipalities, there is still less mobility in the labour market compared to the pre-pandemic situation.

2022 March

- Labour force

- Nordic Region

- Transport

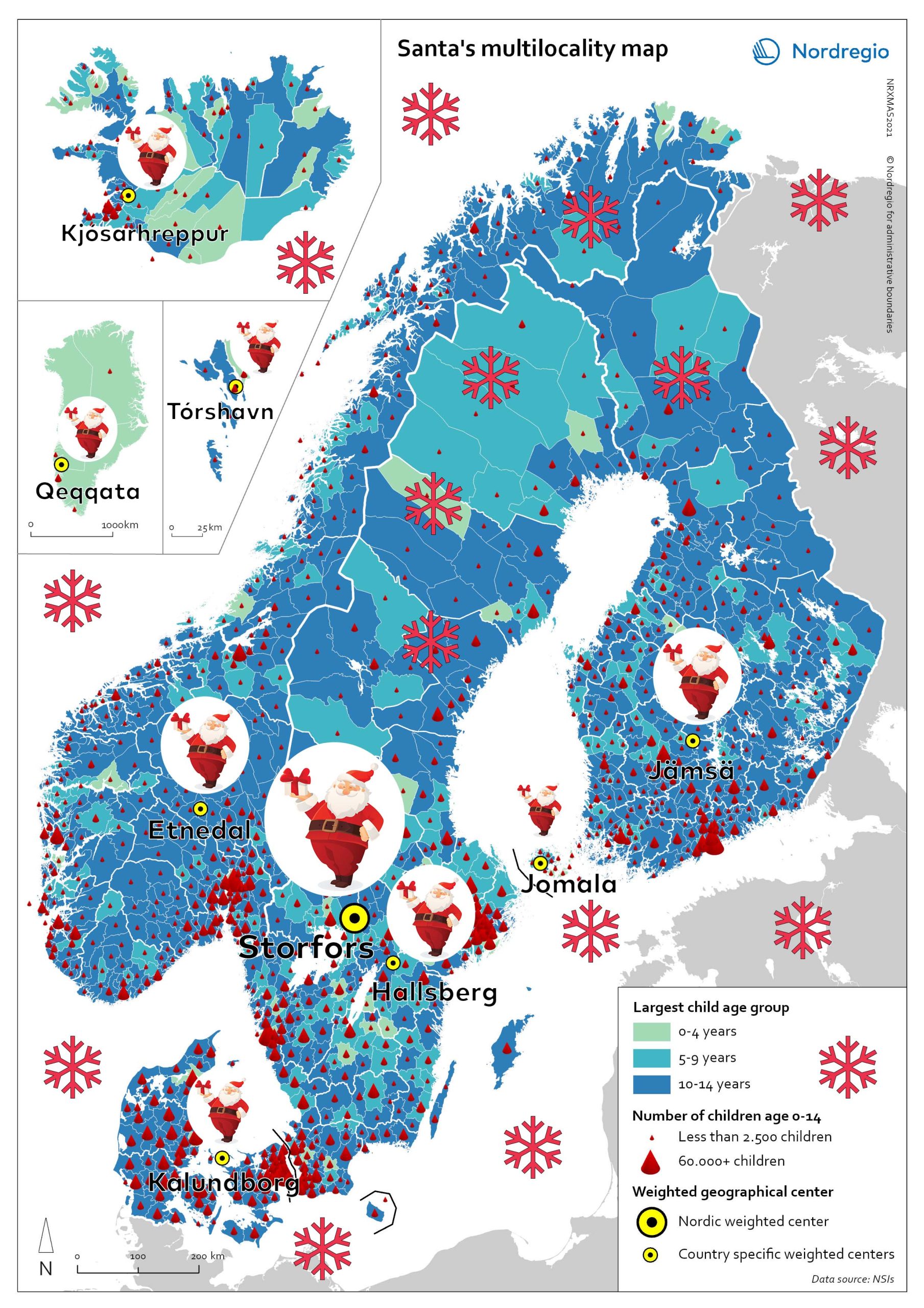

Help Santa to work remotely – where to locate in 2021?

Help Santa! To reduce his transit times and emissions – reindeers burn a lot of (green) fuel – and find an optimal remote workplace from where to deliver gifts to all the children in the Nordic Region! Santa has heard about this new trend “multilocational lifestyle” and he would like to know if this would suit him as well. But where to move? Santa’s little researchers have worked hard this year and done some mapping for him – and discovered places you have never even heard of! If Santa is to serve all children (0-14 years old) throughout the Nordic Region from a single address, the solution lies in Storfors Municipality. WHERE? – you might think. It is a real place, in Central-Southern Sweden. Here Santa has an average distance of 425 km distance to each child from his own backyard. This still sounds like awfully many kilometers. Could he be even more multilocal – with a home in each of the Nordic countries? This would help him to reduce his overall commuting to work significantly. Let’s try it! If he serves all 4.974 children in Åland from a residence (like a luxury hotel with all-inclusive and pets allowed) in Jomala Municipality, he will only have to travel 11 km to work on average. In Greenland, the distances are somewhat larger, and Santa, even with the most optimal location from a residence (a cabin) in Qeqqata Municipality would have to travel 288 km to each of the 11,748 children in the country. Can you guess what the other optimal locations would be in the Nordics? I bet you can’t so I will tell you: it’s the municipalities of Hallsberg in Sweden, Jämsä in Finland, Etnedal in Norway, Kalundborg in Denmark, Kjósarhreppur in Iceland and Tórshavn in Faroe Islands. Well, Santa…

2021 December

- Nordic Region

- Others

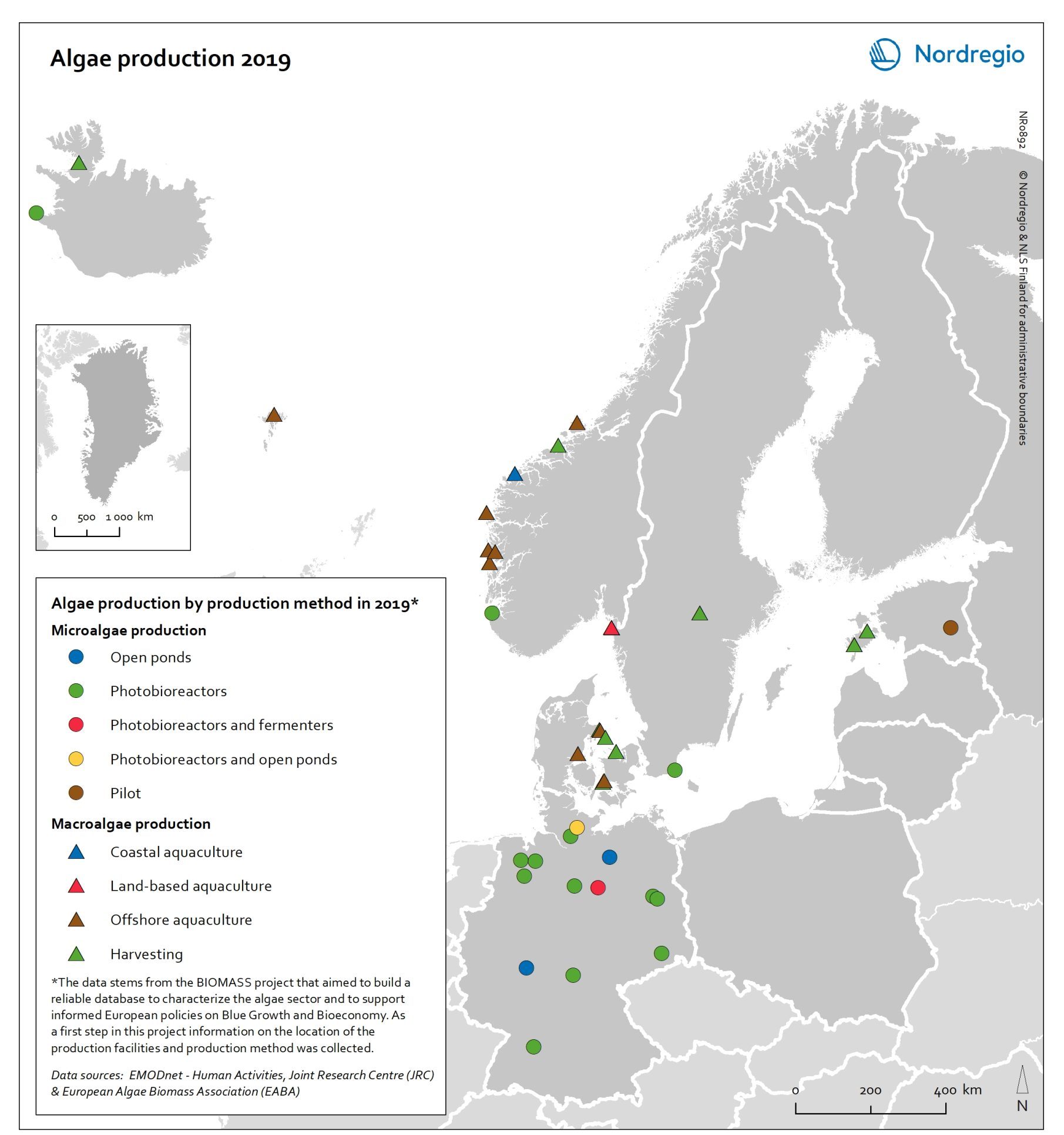

Algae production in 2019

This map shows location of algae production by production method in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea Region in 2019 Algae and seaweeds are gaining attention as useful inputs for industries as diverse as energy and human food production. Aquatic vegetation – both in the seas and in freshwater – can grow at several times the pace of terrestrial plants, and the high natural oil content of some algae makes them ideal for producing a variety of products, from cosmetic oils to biofuels. At the same time, algae farming has added value in potential synergies with farming on land, as algae farms utilise nutrient run-off and reduce eutrophication. In addition, aquatic vegetation is a highly versatile feedstock. Algae and seaweed thrive in challenging and varied conditions and can be transformed into products ranging from fuel, feeds, fertiliser, and chemicals, to third-generation sugar and biomass. These benefits are the basis for seaweed and algae emerging as one of the most important bioeconomy trends in the Nordic Arctic and Baltic Sea region. The production of algae for food and industrial uses has hence significant potential, particularly in terms of environmental impact, but it is still at an early stage. The production of algae (both micro- and macroalgae) can take numerous forms, as shown by this map. At least nine different production methods were identified in the region covered in this analysis. A total of 41 production sites were operating in Denmark, Estonia, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, Germany, and Sweden. Germany has by far the most sites for microalgae production, whereas Denmark and Norway have the most macroalgae sites.

2021 December

- Arctic

- Baltic Sea Region

- Nordic Region

- Others